- 110 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

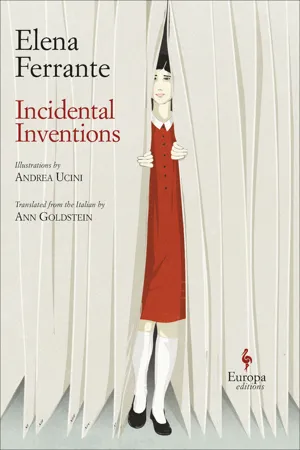

Incidental Inventions

About this book

"Fifty-one columns, short in length but long on wisdom" from the bestselling author of

My Brilliant Friend, an HBO original series (

Minneapolis Star-Tribune).

Collected here for the first time are the seeds of future novels, the timely reflections of this internationally beloved storyteller, the abiding preoccupations of a writer who has been called "one of the great novelists of our time" ( The New York Times).

"This is my last column, after a year that has scared and inspired me . . . I have written as an author of novels, taking on matters that are important to me and that—if I have the will and the time—I'd like to develop within real narrative mechanisms."

With these words, Elena Ferrante bid farewell to her year-long collaboration with the Guardian newspaper. For a full year, she wrote weekly articles, the subjects of which had been suggested by Guardian editors, making the writing process a sort of prolonged interlocution. The subjects ranged from first love to climate change, from enmity among women to the experience of seeing her novels adapted for film and TV.

Translated by Ann Goldstein, the acclaimed translator of Ferrante's novels, and accompanied by Andrea Ucini's intelligent, witty, and beautiful illustrations, this volume is a must for all curious readers.

"A masterclass in style: direct and clear and all the more resonant for it." — The Saturday Paper

"If you are interested in the experience of having a drink with the author and listening to her muse on various subjects . . . here's your answer." —Vulture

Collected here for the first time are the seeds of future novels, the timely reflections of this internationally beloved storyteller, the abiding preoccupations of a writer who has been called "one of the great novelists of our time" ( The New York Times).

"This is my last column, after a year that has scared and inspired me . . . I have written as an author of novels, taking on matters that are important to me and that—if I have the will and the time—I'd like to develop within real narrative mechanisms."

With these words, Elena Ferrante bid farewell to her year-long collaboration with the Guardian newspaper. For a full year, she wrote weekly articles, the subjects of which had been suggested by Guardian editors, making the writing process a sort of prolonged interlocution. The subjects ranged from first love to climate change, from enmity among women to the experience of seeing her novels adapted for film and TV.

Translated by Ann Goldstein, the acclaimed translator of Ferrante's novels, and accompanied by Andrea Ucini's intelligent, witty, and beautiful illustrations, this volume is a must for all curious readers.

"A masterclass in style: direct and clear and all the more resonant for it." — The Saturday Paper

"If you are interested in the experience of having a drink with the author and listening to her muse on various subjects . . . here's your answer." —Vulture

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

The First Time

20 January 2018

Some time ago, I planned to describe my first times. I listed a certain number of them: the first time I saw the sea, the first time I flew in an aeroplane, the first time I got drunk, the first time I fell in love, the first time I made love. It was an exercise both arduous and pointless.

For that matter, how could it be otherwise? We always look at first times with excessive indulgence. Even if by their nature they’re founded on inexperience, and so as a rule are not very successful, we recall them with sympathy, with regret. They’re swallowed up by all the times that have followed, by their transformation into habit, and yet we attribute to them the power of the unrepeatable.

Precisely because of this innate contradiction, my project began to sink right away and shipwrecked conclusively when I tried to describe my first love truthfully. I made an effort to search my memory for details and I found few. He was very tall, very thin, and seemed handsome to me. He was seventeen, I fifteen. We saw each other every day at six in the evening. We went to a deserted alley behind the bus station. He spoke to me, but not much; kissed me, but not much; caressed me, but not much. What primarily interested him was that I should caress him. One evening—was it evening?—I kissed him as I would have liked him to kiss me. I did it with such an eager, shameless intensity that afterwards I decided not to see him again. But already I don’t know if that really happened then, or in the course of other brief loves that followed. Certainly I loved that boy to the point where, seeing him, I lost every perception of the world, and felt close to fainting, not out of weakness but out of an excess of energy.

Consequently, I discovered, what I distinctly remember of my first love is my state of confusion. Or rather, the more I worked on it, the more I focused on deficiencies: vague memory, sentimental uncertainties, anxieties, dissatisfaction. Nothing, in fact, was sufficient; I expected and wanted more, and was surprised that he, on the other hand, after wanting me so much, found me superfluous and ran away because he had other things to do.

All right, I said to myself, you will write about how altogether wanting first love is. But, as soon as I tried, the writing rebelled, it tended to fill gaps, to give the experience the stereotypical melancholy of adolescence. It’s why I said, that’s enough of first times. What we were at the beginning is only a vague patch of colour contemplated from the edge of what we have become.

Fears

27 January 2018

I’m not brave. Most of all I’m afraid of anything that creeps, and especially snakes. I’m afraid of spiders, woodworms, mosquitoes, even flies. I’m afraid of heights, and of elevators, cable cars, aeroplanes. I’m afraid of the very ground we stand on when I imagine that it might split open or, because of a sudden breakdown in the workings of the universe, fall down, as in the nursery rhyme we recited as children, playing ring around the rosy. Ring around the rosy, The world falls down, The earth falls down, All fall down: ah, how those words terrified me. I’m afraid of all human beings when they become violent: I’m afraid of them when they shout, when they insult, when they wield words of contempt, clubs, chains, weapons that slash or shoot, atomic bombs.

And yet, as a child, whenever it was necessary to appear fearless, I appeared fearless. I soon got used to being less afraid of dangers, whether real or imaginary, and began to fear more, much more, the moment when others reacted as I hadn’t known how to react. My girlfriends shrieked because there was a spider? I overcame my disgust and killed it. The man I loved proposed a vacation in the mountains with the obligatory rides on a chairlift? I was dripping with sweat, but I went.

Once, the cat brought in a snake and left it under my bed, and I, with a broom and dustpan, screaming, chased it out. And if someone threatens my daughters, or me, or any human being, or any harmless animal, I resist the desire to run away.

Popular opinion has it that people who react as stubbornly as I’ve trained myself to have real courage, which consists precisely in overcoming fear. But I don’t agree. We fearful belligerents place at the top of all our fears the fear of losing self-respect. We value ourselves very highly, and in order not to have to face our own humiliation, we are capable of anything. In other words, we drive away our fears not out of altruism but out of egotism.

And so, I have to admit, I’m afraid of myself. I’ve known for a long time now that I can get carried away, so I’m trying to soften the aggressive reactions I’ve forced myself to have ever since I was a child. I’m learning, like a character in Conrad, to accept fear, even to exhibit it with self-mockery. I began to do this when I realised that my daughters got scared if I defended them from dangers—small, large or imaginary—with excessive ardour. What perhaps should be feared most is the fury of frightened people.

Keeping a Diary

3 February 2018

I kept a diary for several years as a girl. I was a timid adolescent; all I said was yes, and mostly I was silent. In my diary, on the other hand, I let go: I recounted in detail what happened to me every day, very secret events, bold thoughts. So I was really worried about it: I was afraid that my family, especially my mother, would find it and read it. Thus I was always inventing safe hiding places that soon seemed to me unsafe.

Why was I worried? Because if, in everyday life, I was so embarrassed, so cautious, that I scarcely breathed, the diary produced in me a craving for truth. I thought that when one writes, it makes no sense to be contained, to censor oneself, and as a result I wrote mostly—maybe only—about what I would have preferred to be silent about, resorting among other things to a vocabulary that I would never have dared to use in speaking.

This soon created a situation that exhausted me. On the one hand, I made an effort of expression every day to demonstrate to myself that I was ruthlessly honest, and that nothing would ever prevent me from being so; on the other, I was terrified that someone might set eyes on my pages.

That contradiction was with me for a long time, and in many ways it’s still alive today. If I chose to make visible in writing what, if I hadn’t written, would have remained completely hidden in my head, why then was I anxious that my diary might be discovered?

Around the age of twenty, it seemed to me I’d found a solution that satisfied me. I had to stop writing my diary and channel the desire to tell the truth—my most unutterable truths—into an invented story. I took that route partly because the diary itself was starting to become fiction. Very often, for example, I didn’t have time to write every day, and as a result it seemed to me that the thread of causes and effects was broken. So I filled the voids by writing pages that I later back-dated. And in doing so I gave the facts, the reflections a coherence that didn’t always exist in the pages that I wrote daily. So it was probably the experience of the diary and its contradictions that transformed me into a fiction writer. In the invented stories, I felt that I was—I and my truths—a little safer.

In fact, as soon as that new writing gained ground, I threw away my diaries. I did it because the writing seemed crude, without worthwhile thoughts, full of childish exaggerations and, above all, far removed from how I now remembered my adolescence. Since then, I’ve no longer felt the need to keep a diary.

The End

10 February 2018

More and more often I hear my friends say: it’s not death that scares me but illness. And I, too, repeat the phrase. When I try to unpack it to understand it a little better, I discover that for me it means: I’m frightened not by the idea of ceasing to exist, but by the invasiveness of treatments, by the oscillation between the illusion of recovery and disappointment, by death throes. It’s as if I were confessing that what truly worries me is the end of good health, along with everything that that entails: debilitation, progressive inactivity, pleasure diminished to the simple assertion that I am still “I,” and that for now, somehow or other, I’m still alive.

As a result, the idea of death itself seems increasingly pallid. What is terrifying, instead, is the end of enjoyable life, of a full life. And for me that’s because the belief in some kind of beyond, acquired during childhood, has faded over time.

When I was a child, my grandmother was the most active person in the house; then she had a stroke and was paralysed for years. She sat in a corner of the kitchen and I, as a girl, didn’t experience her suffering and humiliation, nor did she signal it to me, even with her eyes, as something intolerable. Death came suddenly, and I grieved within the religious framework in which I’d been raised. Death meant that she had gone away, leaving a body reduced to a cold, rigid thing. Her dying had very precise features: I felt it as a terrifying immobility and a very mysterious movement. My grandmother had crossed over into an elsewhere.

Later, every form of religious belief seemed absurd to me, and death was as if disfigured. The immobility remained, the movement vanished. The dead body became simply the sign of the end of life in a specific individual. Today I would never say: he has gone away. I’ve lost the sense of the crossing over: nothing goes up to heaven, we don’t move to another world, we don’t return, we aren’t reborn. We remain definitively immobile; death is the last point on the segment of life that has chanced to be ours.

Thus my attention, like that of many others, is concentrated not on dying but on living poorly. We hope that life is as long as possible, and yet that it will end conclusively when we have declined to the point where no treatment can make it tolerable. I don’t know which is better: this adult belief or the belief I maintained until adolescence. Beliefs aren’t good or bad; they serve only to bring order, at least momentarily, to our anguish.

The False and the True

17 February 2018

I can’t trace a line of separation between fiction and nonfiction. Let’s say I have an idea for a story in which, at the age of forty-eight, in an empty country house in winter, I am locked in the shower cubicle, I can’t turn the water off, the hot water is used up. Did that really happen to me? No. Did it happen to a person I know? Yes. Was that person forty-eight? No.

Why then do I construct a story in the first person, as if it had happened to me? Why do I say it was winter when, in fact, it was summer, why do I say the hot water was used up when it wasn’t, why do I make the woman’s imprisonment last for hours, when the actual person got out in five minutes, why do I complicate the story with many other events, with ...

Table of contents

- ALSO BY ELENA FERRANTE

- INCIDENTAL INVENTIONS

- Collisions

- The Pieces

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Incidental Inventions by Elena Ferrante,Andrea Ucini, Ann Goldstein in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & European Literary Collections. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.