![]()

CHAPTER 1

NBC (1950)

Courtesy of NBCUNIVERSAL Media, LLC

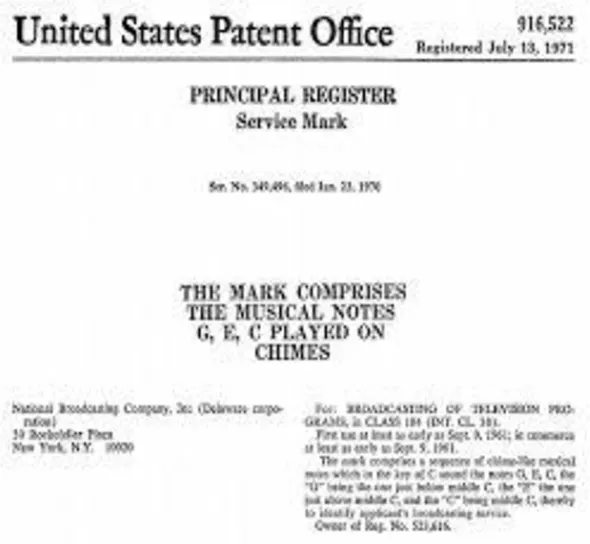

Three notes. N-B-C. The godfather of sonic logos. It has stood the test of time. In 1950,1 we know that the NBC chimes (“G-E-C”) became the first “purely audible” service mark2 (any word, name, symbol, or device, or any combination thereof) granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.3 It became the first sound mark. “A sound mark identifies and distinguishes a product or service through audio rather than visual means. Examples of sound marks include: (1) a series of tones or musical notes, with or without words, and (2) wording accompanied by music.”4

The back story for the chimes’ “G-E-C” sequence is that it comes from the initials of the General Electric Company (GE). In 1987, Robert C. Wright, the president and CEO of NBC, testified before the U.S. Congress that “Not everyone knows that GE was one of the original founders of RCA, NBC’s former parent, and that the notes of the famous NBC chimes are G-E-C, standing for the General Electric Company.”5 The sound mark was originally issued to General Electric Broadcasting.6 The official description, as recorded by its registration at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, is:

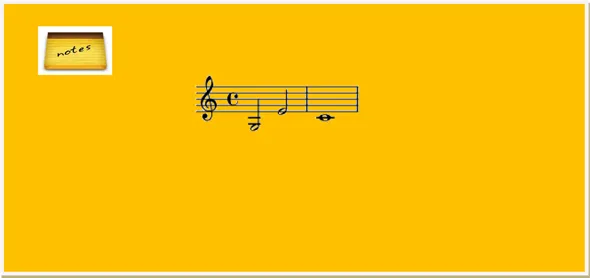

The mark comprises a sequence of chime-like musical notes which are in the key of C and sound the notes G, E, C, the “G” being the one just below middle C, the “E” the one just above middle C, and the “C” being middle C, thereby to identify applicant’s broadcasting service.7

NBC Chimes sound trademark, Serial No. 72349496, Registration No. 0916522

The original filing it said:

A sound mark depends upon aural perception of the listener which may be as fleeting as the sound itself unless, of course, the sound is so inherently different or distinctive that it attaches to the subliminal mind of the listener to be awakened when heard and to be associated with the source or event with which it is struck. With “unique, different, or distinctive sounds.” That “consumers “recognize and associate the sound with the offered services . . . exclusively with a single, albeit anonymous, source.8

History

We know that on November 29, 1929, the NBC Chimes sounded for the first time (at 59 minutes 30 seconds, and 29 minutes 30 seconds past the hour). But the inspiration and creation of the notes depends on who you are asking.

The earliest known sound recording of a musical dinner chime being used to identify a local radio station is that of WSB Atlanta. The radio voice of The Atlanta Journal, WSB signed on the air on March 15, 1922. Two of the station’s earliest stars were the twin sisters Kate and Nell Pendley; according to Cox Broadcasting’s history of WSB Welcome South, Brother, published in 1974, WSB manager Lambdin Kay was looking for a distinctive identification to close each program, and Nell Pendley offered him her Deagan Dinner Chimes. Kay created an identifier by ringing the notes E–C–G, the first three notes of the popular WWI song “Over There” and WSB in Atlanta in addition to being the first station to adopt a three-chime signature, it was directly responsible for NBC’s chimes. This explanation states that, as an NBC affiliate, WSB was hosting a network broadcast of a Georgia Tech college football game, and NBC staff at the network’s New York City headquarters heard the WSB chimes, which prompted them to ask permission to adopt it for use by the national networks.9

An alternative birthplace involves WJZ.

In July of 1921, RCA bought WJZ from Westinghouse, and five years later, in July of 1926, they bought WEAF from AT&T. The National Broadcasting Company was incorporated by RCA on September 8, 1926, and two months later, on November 15, the NBC Radio Network debuted. In those early days, at the end of a programs, the NBC announcer would read the call letters of all the NBC stations carrying the program. As the network added more stations this became impractical and would cause some confusion among the affiliates as to the conclusion of network programming and when the station break should occur on the hour and half-hour. Some sort of coordinating signal was needed to signal the affiliates for these breaks and allow each affiliate to identify. Three men at NBC were given the task of finding a solution to the problem and coming up with such a coordinating signal. These men were; Oscar (O.B.) Hanson, from NBC engineering, Earnest LaPrada, an NBC orchestra leader, and Phillips Carlin, an NBC announcer. During the years 1927 and 1928 these men experimented with a seven note sequence of chimes, G-C-G-E-G-C-E, which proved too complicated for the announcers to consistently strike in the correct order. Sometime later they came up with the three note G-E-C combination.10

Now you know that the only thing that is clear about the origination of the NBC Chimes are the notes G-E-C and its longevity. The takeaway from this sonic logo is that sometimes the simple things in life and logos are the most memorable.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

JAWS (1975)

Courtesy of Universal Studios Licensing LLC

Before Shark Week, there was Jaws and that music. “F to F sharp. With those two notes, composer John Williams ensured that venturing into water would never feel safe again.”1 Meet John Williams who used a lot of instruments to introduce a mechanical shark and the rest is history.

Rarely have six basses, eight celli, four trombones and a tuba held more power over listeners. Especially in a movie theatre. John Williams’s score for Jaws ranks as some of the most terrifying music ever written for the cinema. The music of Jaws was as responsible as filmmaker Steven Spielberg’s imagery for scaring people out of the water in the summer of 1975. Its sheer intensity and visceral power helped to make the film a global phenomenon; Spielberg compared it to Bernard Herrmann’s equally frightening, indelible music for Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). Williams viewed Spielberg’s thriller about a giant Great White shark terrorising New England beachgoers as a chance for music to make a major contribution. First to come—and the only music that Williams demonstrated for Spielberg prior to the recording sessions—was the shark motif. “I played him the simple little E-F-E-F bass line that we all know on the piano,” and Spielberg laughed at first. But, as Williams explained, “I just began playing around with simple motifs that could be distributed in the orchestra, and settled on what I thought was the most powerful thing, which is to say the simplest. Like most ideas, they’re often the most compelling.” According to Williams, Spielberg’s response was: “Let’s try it.” Jaws not only became the highest-grossing film of its time; it propelled John Williams into the front rank of modern film composers. He won his second Academy Award for the score as well as a Golden Globe, a Grammy, and BAFTA’s Anthony Asquith Award for film music. As Spielberg later put it: “I think the score was clearly responsible for half of the success of that movie.”2

(By permission: Limelight Arts Media Pty Ltd (c))

In a career that spans five decades, John Williams has become one of America’s most accomplished and successful composers for film and for the concert stage. Williams has composed the music and served as music director for more than one hundred films. His 40-year artistic partnership with director Steven Spielberg has resulted in many of Hollywood’s most acclaimed and successful films, including Schindler’s List, E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, Jaws, Jurassic Park, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, four Indiana Jones films, Saving Private Ryan, Amistad, Munich, Hook, Catch Me If You Can, Minority Report, A.I.: Artificial Intelligence, Empire of the Sun, The Adventures of Tintin, and War Horse. Williams has composed the scores for all of George Lucas’ Star Wars films, the first three Harry Potter films, Superman: The Movie, JFK, Born on the Fourth of July, Memoirs of a Geisha, Far and Away, The Accidental Tourist, Home Alone, Nixon, The Patriot, Angela’s Ashes, Seven Years in Tibet, The Witches of Eastwick, Rosewood, Sleepers, Sabrina, Presumed Innocent, The Cowboys, and The Reivers, among many others. Williams has received five Academy Awards and 50 Oscar nominations, making him the Academy’s most-nominated living person and the second-most nominated person in the history of the Oscars. He also has received seven British Academy Awards (BAFTA), 22 Grammys, four Golden Globes, five Emmys, and numerous gold and platinum records.3

On January 10, 1977, during the final days of the Ford administration, John Williams began writing music for Star Wars, a forthcoming sci-fi adventure film created by George Lucas. More than forty-two years later, on November 21, 2019, Williams presided over the final recording session for The Rise of Skywalker, the ninth and ostensibly last installment of the main Star Wars saga. Williams scored every film in the series, and there is no achievement quite like it in movie history, or, for that matter, in musical history. Williams composed more than twenty hours of music for the cycle, working with five different directors. He developed a library of dozens of distinct motifs, many of them instantly recognizable to a billion or more people. The Star Wars scores have entered the repertories of the most venerable orchestras around the world. When, earlier this year, Williams made his début conducting the Vienna Philharmonic, several musicians asked him for autographs. Williams is a courtly, soft-voiced, inveterately self-effacing man of eighty-eight. He is well aware of the extraordinary worldwide impact of his Star Wars music—not to mention his scores for Jaws, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, E.T., the “Indiana Jones” movies, the “Harry Potter” movies, the “Jurassic Park” movies, and dozens of other blockbusters—but he makes no extravagant claims for his music, even if he allows that some of it could be considered “quite good.” A lifelong workhorse, he resists looking back and immerses himself in the next task. In the coronavirus period, he has been at home, on the west side of Los Angeles, focusing on a new concert work—a concerto, for the violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter, which will have its première next year. In February, I visited Williams in his bungalow office on the Universal Studios back lot—part of an adobe-style complex belonging to Amblin Entertainment, Steven Spielberg’s production company. Spielberg’s office is nearby. The two men first worked together on The Sugarland Express, in 1974, and have collaborated on twenty-eight films to date—all but four of Spielberg’s features. At a tribute, in 2012, Spielberg said, “John Williams has been the single most significant contributor to my success as a filmmaker.” It is, however, Star Wars that anchors the composer’s fame. Williams poured himself a glass of water in the bungalow kitchenette, settled into a chair in front of his desk, and addressed the topic of the Star Wars cycle. He is a tall man, still physically vigorous, his face framed by a trim, vaguely clerical white beard. “Thinking about it, and trying to speak about it, connects us with the idea of trying to understand time,” he said. “How do you understand forty years? I mean, if someone said to you, ‘Alex, here’s a project. Start on it, spend forty years on it, see where you get’? Mercifully, I had no idea it was going to be forty years. I was not a youngster when I started, and I feel, in retrospect, enormously fortunate to have had the energy to be able to finish it—put a bow on it, as it were.” In the mid-1970s, when Williams formed links to the young blockbuster directors Spielberg and Lucas, he was already well established in Hollywood. He was, in a sense, born into the business; his father, Johnny Williams, was a percussionist who played in the Raymond Scott Quintette and later performed on movie soundtracks. Williams worked several times with Bernard Herrmann, perhaps the greatest American film composer, celebrated for his scores for Citizen Kane, Vertigo, Psycho, and Taxi Driver. Williams, who sometimes joined his father at rehearsals, told me, “Benny liked the way my father played the timpani. ‘Old Man Williams isn’t afraid to break the head,’ he’d say. Benny was a famously irascible character, but in later years he was always very encouraging to me. One time he got irritated was when I arranged ‘Fiddler on the Roof.’ ‘Write your own music,’ he said.” The Williamses moved from the New York area to Los Angeles in 1947, when John was fifteen. A skilled pianist, he won notice for organizing a jazz group with classmates from North Hollywood High; a brief piece in Time referred to him as Curley Williams. In 1955, he went to New York and studied at Juilliard with the great piano pedagogue Rosina Lhévinne. “It became clear,” he says,...