![]()

SECTION I

Curriculum Introduction

![]()

CHAPTER 1

WHEREVER YOU GO, THERE YOU ARE

THE NEED FOR EDUCATIONAL MAPS IN THE CHURCH

James Riley Estep Jr.

Are we there yet?” “How much further?” “When are we going to stop?” No parent escapes these perennial questions. Family trips are taken with intentionality; they are not about wandering around directionless or without purpose. They usually include a destination, a desired location to reach at an optimal time with arrangements made for the trip. We are typically not pioneers, boldly going into untamed territory, blazing new trails, charting a course to an unknown destination. Rather, we check atlases and the GPS, map out travel routes, or go online to AAA or another travel service to make sure we are going in the right direction and will reach our destination. We do not want to lose time wandering around aimlessly and getting lost. We need maps.

We are travelers in the Christian faith, not wanderers. The Bible speaks of people wandering in the wilderness as a chastisement (Num 32:13; 2 Kgs 21:8), rather than moving intentionally toward the land God had promised them. While it may seem that wandering is not bad for a short time, wandering for a lengthy time or throughout life is indeed perilous. In the Bible, wandering is typically associated with unfaithfulness; like the lone sheep in Jesus’ parable (Matt 18:12–14), there is implicit danger in choosing to wander from the wisdom of God, usually with disastrous consequences. Jude 13 even describes false teachers as “wandering stars, for whom blackest darkness has been reserved forever” (emphasis added). The apostle Paul went on journeys, intentional travels, and was indeed more productive (Acts 13–14; 15:36–21:8, esp. 15:36); just as Jesus had demonstrated intentionality in his traveling through Palestine, moving the disciples through northern Galilee (Jewish), into the Decapolis region (Greek), and into Samaria before entering Judea and Jerusalem as preparation for his disciples’ global mission. In short, wandering is not for Christians. We want to be travelers through the Christian life, not wanderers. Exploring and discovery learning have their place, but they supplement the main journey; they do not replace it.

Curriculum is the Church’s map to spiritual maturity. It is the intentional direction given by mature believers to those who are new to the Christian faith. It is the lessons learned from 2,000 years of the Christian faith given to the contemporary church as a means of guiding us into a faithful walk and work with Christ. God gave the church as a means of directing people toward himself, and curriculum is the means by which the church maps the travel path toward Christlike maturity. Educational “maps” are simply the intentional plans made by the church for carrying out the task. The plans and their implementation are known as curriculum.

What Is Curriculum?

Defining curriculum is a daunting task. The word itself comes from the Latin currere, literally meaning “to run”; it came to mean the components of a course of study, the direction of one’s race in life, such as in preparing a curriculum vita to demonstrate the path one has traveled through life in preparation for a career. Educationally, definitions are varied, ranging from curriculum as a packet of materials purchased from a publishing company to all the experiences one encounters in life or in the congregation. Arthur Ellis describes curriculum as prescription (i.e., what you have to know, knowledge-content focused) and experience (i.e., everything from which you learn, learner-child focused). Figure 1.1 expands on this spectrum of curriculum’s definitions and is primarily based on the nature of its content and upon what it is centered.

So, how can one define curriculum? In fact, it almost defies definition. Perhaps the most common facet to understanding curriculum is content: “What did you teach today?” “Oh, Joshua and the battle of Jericho,” or perhaps worse, “Pages 45–61 of the teacher’s guide.” Content is an inescapable element in understanding curriculum, but not the only one. Objectives are another way to grasp the meaning of the curriculum. Rather than focusing on what is taught, this dimension emphasizes why it is being taught. When someone asks, “What will I get out of this class?” or “If I participate in small groups for two years, what is the take-away from it?” they are asking about objectives. Whereas the previous dimension focuses on content, this one focuses on the learner’s learning—what they get out of it.

Figure 1.1: Spectrum of Curriculum

The “what” and the “why” are perhaps the two most influential dimensions in understanding curriculum. James E. Plueddemann’s seminal question “Do we teach the Bible or do we teach students?” reflects these two primary depictions of curriculum. As a matter of fact, we do both. Curriculum is both what we teach and also the desired objectives we have in the lives of our learners. For example, take the subject of spiritual disciplines. A cognitive objective might be stated, “The student will understand the spiritual disciplines,” requiring the content to teach them about the spiritual disciplines, such as their history, theology, and definition. An affective objective, one that is more experiential or internal, may say, “The student will experience the benefits of the spiritual disciplines,” requiring them to practice them for a time and perhaps journal their experience, which becomes the content relevant to this objective. Of course, all this assumes they know how to practice the spiritual disciplines. A more volitional objective, such as an ability or skill, would mean the content would have to focus on the how-to, the step-by-step process, rather than just information about spiritual disciplines. Hence, the three basic forms of objectives (cognitive, affective, and volitional) interact with one another to provide a comprehensive approach to learning through the curriculum. If the curriculum is to serve as a roadmap for discipleship, then “the curriculum, as a key or instrument of education, must guide the learner to be and become a ‘response-able’ disciple of Jesus Christ.” This requires the objectives and content to be more than the recitation of head knowledge. Learners need a deeper level of cognitive assent capable of reasoning through life from a Christian perspective, as well as concern for the affective and volitional domains of learning.

However, curriculum is more than just an alignment of content with the intended learning objectives. For example, the definition of curriculum is also impacted by the assumed relationship shared by the teacher and learners, as well as the preferred or required teaching methods. The “who” and “how” dimensions of understanding curriculum are likewise critical to conceptualizing a definition. The “what” and “why” somewhat determine the “who” and “how.” For example, if a congregation wants to equip its members to do evangelism, lecturing them about the necessity of evangelism is probably not the best method, especially since the teachers’ relationship to the participants are limited given the lecture method being used. However, if the curriculum dictates a hands-on approach, the teacher is required to assume the role of a mentor (relationship) more than a lecturer, and actually asks the participants one at a time to participate with them in the process of evangelism. Curriculum has implications for the teacher’s place in the educational process and the most advantageous instructional methodology.

So, what is curriculum? In short, the answer is all. Curriculum is all of this. It is a collectively cumulative matter. It is not any one of these dimensions, but all of them. Curriculum is essentially the plan for how all the lessons, experiences, and relationships collectively nurture, equip, and mentor a learner toward a desired set of objectives; all of which dictates how we do education in the church. It is the tangible representation and incarnation of our educational philosophy. It is the roadmap that the educational ministry of the congregation follows. It enables an assessment of the congregation’s progress along the faith journey. It informs the education ministry’s decision-making process for future direction and development of the teaching ministry of the church.

Education without curriculum is like biblical interpretation without hermeneutics. Without a roadmap, an articulated recognizable curriculum, the education ministry lacks intentionality and creates bewildered wanderers rather than faithful pilgrims. Curriculum is the capstone of education in the church, the expression of the ideal result of the education ministry.

A Tale of Three Curricula

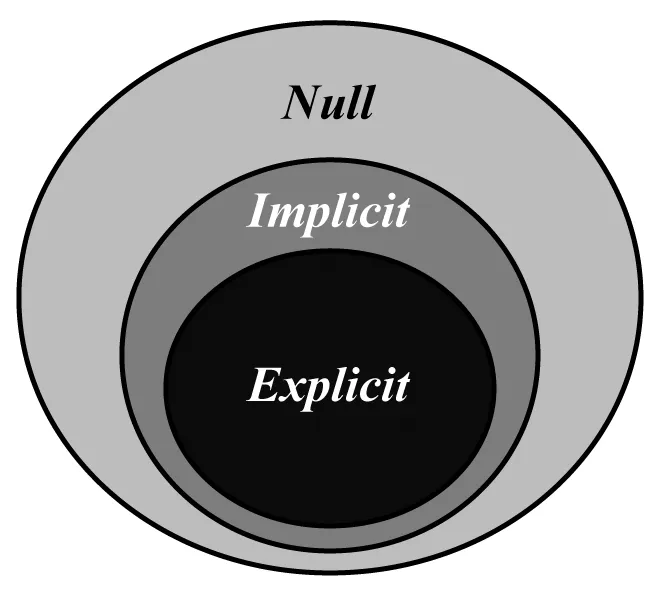

“What we need is a comprehensive curriculum!” A congregation’s curriculum is expressed in three ways, and hence a comprehensive curriculum is comprised of three simultaneously interacting layers of curriculum (fig. 1.2). The explicit curriculum is the most readily recognized layer. It is what the congregation openly espouses. When a congregation articulates its intended learning objectives for a class, program, or even the congregation as a whole, this is the explicit curriculum. It is perhaps best represented by the content of instruction and the programs comprising the education ministry. For example, if a congregation explicitly states, “We want our members to know biblical doctrine,” then we would expect adult Bible fellowship or classroom studies on Bible content, theology, or history of their theological tradition. We would expect to see classes on Romans or Galatians, studies on justification and sanctification, and perhaps even a survey of the church’s articles of faith. Unfortunately, most individuals see the explicit curriculum as the only curriculum; they perceive curriculum to be mono-layered, failing to identify the other two layers and their impact on the congregation.

The implicit curriculum is best described by what we learn from our experience of the congregation. It is sometimes referred to as the hidden curriculum. It may not be explicit, but it is what we learn from our experience within the class, program, or congregation. For example, in a higher education classroom, a syllabus has stated learning objectives (explicit); but if a professor will not accept late homework or counts a tardy as an absence, while it is not part of the explicit curriculum, the implicit curriculum teaches the learner to be on time.

Figure 1.2: Three Curricula

Perhaps the best way to express this difference i...