- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Community Character provides a design-oriented system for planning and zoning communities but accounts for how people who participate in a community live, work, and shop there. The relationships that Lane Kendig defines here reflect the complexity of the interaction of the built environment with its social and economic uses, taking into account the diverse desires of municipalities and citizens. Among the many classifications for a community's "character" are its relationship to other communities, its size and the resulting social and economic characteristics.

According to Kendig, most comprehensive plans and zoning regulations are based entirely on density and land use, neither of which effectively or consistently measures character or quality of development. As Kendig shows, there is a wide range of measures that define character and these vary with the type of character a community desires to create. Taking a much more comprehensive view, this book offers "community character" as a real-world framework for planning for communities of all kinds and sizes.

A companion book, A Practical Guide to Planning with Community Character, provides a detailed explanation of applying community character in a comprehensive plan, with chapters on designing urban, sub-urban, and rural character types, using character in comprehensive plans, and strategies for addressing characteristic challenges of planning and zoning in the 21st century.

According to Kendig, most comprehensive plans and zoning regulations are based entirely on density and land use, neither of which effectively or consistently measures character or quality of development. As Kendig shows, there is a wide range of measures that define character and these vary with the type of character a community desires to create. Taking a much more comprehensive view, this book offers "community character" as a real-world framework for planning for communities of all kinds and sizes.

A companion book, A Practical Guide to Planning with Community Character, provides a detailed explanation of applying community character in a comprehensive plan, with chapters on designing urban, sub-urban, and rural character types, using character in comprehensive plans, and strategies for addressing characteristic challenges of planning and zoning in the 21st century.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Community Character by Lane H. Kendig,Bret C. Keast in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The Designer’s Lexicon

Planning for community character requires that architects, planners, urban designers, policymakers, and citizens clearly communicate their goals. Planners must then write plans and ordinances to enable those goals to be met. Unfortunately, many of these groups seem to speak different languages. There are a considerable number of terms used by architects and urban designers that are not commonly used by citizens, elected officials, and planners. Likewise, planners tend to use a number of terms typically found only in zoning ordinances.

To help facilitate the discussion about community character goals, this chapter introduces a design and planning lexicon. A great number of the urban design and architecture terms have been in the literature for decades. This is true of some of the planning and landscape terms as well. In developing community character for suburban and rural areas, I have developed additional terms over the past thirty years.

This chapter is organized by topical areas, so terms are grouped by their relation to one another rather than alphabetically. It begins with three terms that describe major classes of character, and then explores space, mass, and other elements of which they are made. Another set of terms addresses organizing buildings or spaces. The chapter concludes with landscape terms, which address the physical environment, along with planning and zoning terms.

There are a number of terms that describe aspects of communities and human settlements. Three descriptive ways of relating to space are discussed here—architectural, garden, and landscape—which connect to how the three classes of character (urban, sub-urban, and rural) are seen.

Figure 1-1. Architectural space: created by buildings. Stockholm, Sweden.

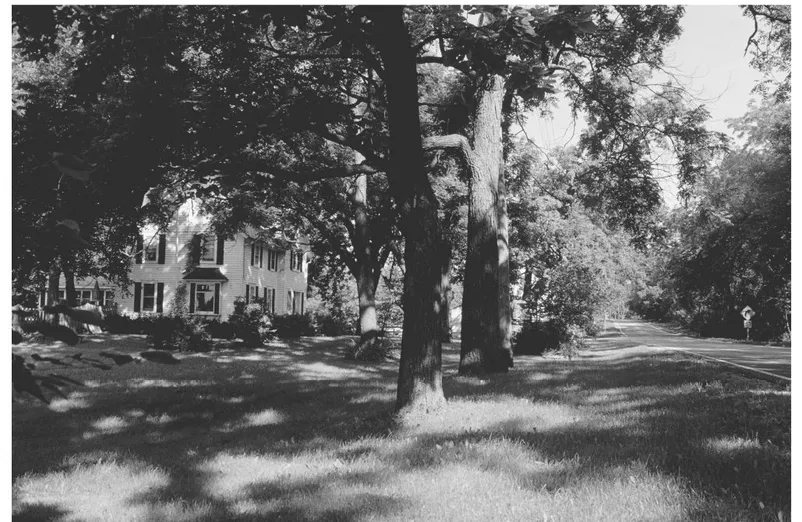

Figure 1-2. Garden-like space: created by trees that shelter and surround buildings. McHenry County, Illinois.

Figure 1-3. Landscape: view across a field to the horizon. Chattahoochee Hill Country, Georgia.

DESCRIPTIVE TERMS

Architectural Space

This describes outdoor space that is enclosed by man-made structures to house businesses or families (see figure 1-1). Buildings and their layout define architectural space. The design of the space itself is architectural. Spaces are paved and greenery is limited to small planters or tiny yards. In general, impervious surfaces, buildings, roads, plazas, and parking occupy nearly all the land in architectural spaces.

Garden-Like

The term “garden-like” refers to a space in which landscape elements provide a setting for the building (see discussion of negative space, below). The space is green and pervious rather than paved (see figure 1-2). Garden-like is intended to represent the presence of vegetative mass that is equal to or greater than the building mass, and whose height is generally greater than that of the buildings. Its green nature and softer shapes directly contrast with the hard-edged architectural environment.

Landscape

The term “landscape” is intended to evoke a natural or agricultural environment that extends to the horizon (see figure 1-3). A landscape requires that the built environment be in the background and trivial. Landscape planning follows the same rules as landscape painting in that buildings and communities are diminished to background elements or hidden from view. A landscape exists when one can see to the horizon in all directions without buildings breaking the horizon line (see the section on infinite space, below). Their other characteristic is that as people or cars move through them, landscapes seem to flow or expand as the horizon changes with movement.

Mass

Buildings, stands of vegetation, and landforms are all volumes that occupy and fill space; visually, they appear as solids. Whether they are truly solids (as is the case with a large boulder), hollow (as a structure containing rooms), or spongy (as a dense stand of vegetation with a visual shell of leaves) is immaterial. It is the visual characteristic that is important. Solids are visual elements that are shown on plans. They can also be walls that are two-dimensional, having little volume. Solids may contain human activity within them, may contain a space, or may serve only as a visual barrier. Mass can also be considered positive volume that occupies space visually.

Space

In planning communities, space means exterior space, open to the sky. Architects use this concept of space, but they also use the term to refer to interior spaces (rooms). Space may be pervasive, as it is at sea, where it is unlimited to the horizon. At the other end of the spectrum it can be a tightly contained void or area between surrounding walls or buildings. For this reason different types of space are defined.

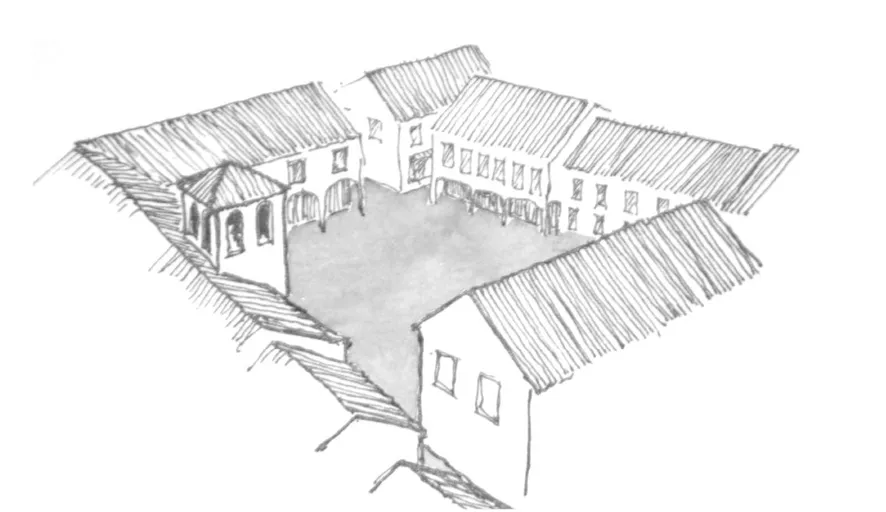

Positive space (see figure 1-4) is exterior space enclosed by buildings or walls (basically an outdoor room). Positive space is sometimes referred to as centripetal1—that is, the space pulls or focuses activities inward. The degree of enclosure is very important for a positive space. Failure to provide enclosure weakens the space. Enclosure, which contains and focuses activity, is a key element in urban design and is a measurable concept (see the section on distance/height, or D/H, ratio, page 31). It is also appropriate, in most cases, to consider positive space as architectural space since it is inseparable from its surrounding buildings and their architecture.2

Figure 1-4. Positive space: buildings surround space.

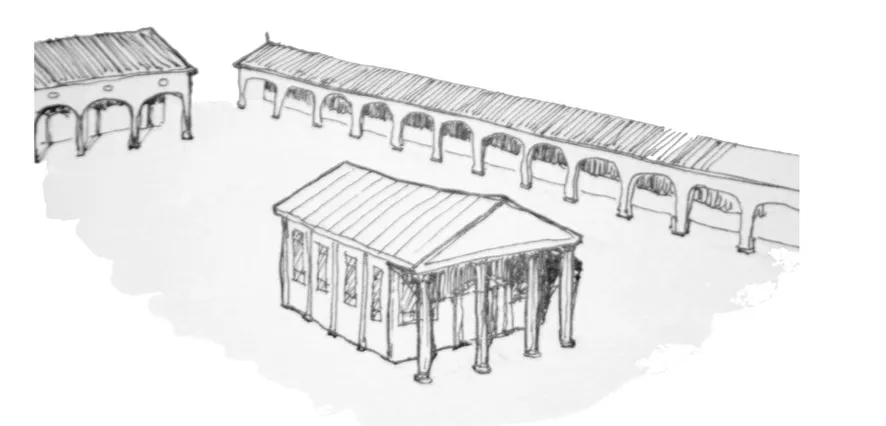

Figure 1-5. Negative space: space surrounds building.

Negative space is space that surrounds a building, as in figure 1-5. The space is considered ...

Table of contents

- About Island Press

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- INTRODUCTION - Why Should We Care About Community Character?

- CHAPTER 1 - The Designer’s Lexicon

- CHAPTER 2 - Community State, Context, and Scale

- CHAPTER 3 - Community Character Classes and Types

- CHAPTER 4 - Community and Regional Forms

- CHAPTER 5 - Community Character Measurement

- CHAPTER 6 - Conclusion

- Notes

- Index

- Island Press | Board of Directors