eBook - ePub

Epidemics, Empire, and Environments

Cholera in Madras and Quebec City, 1818–1910

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Throughout the nineteenth century, cholera was a global scourge against human populations. Practitioners had little success in mitigating the symptoms of the disease, and its causes were bitterly disputed. What experts did agree on was that the environment played a crucial role in the sites where outbreaks occurred. In this book, Michael Zeheter offers a probing case study of the environmental changes made to fight cholera in two markedly different British colonies: Madras in India and Quebec City in Canada. The colonial state in Quebec aimed to emulate British precedent and develop similar institutions that allowed authorities to prevent cholera by imposing quarantines and controlling the disease through comprehensive change to the urban environment and sanitary improvements. In Madras, however, the provincial government sought to exploit the colony for profit and was reluctant to commit its resources to measures against cholera that would alienate the city's inhabitants. It was only in 1857, after concern rose in Britain over the health of its troops in India, that a civilizing mission of sanitary improvement was begun. As Zeheter shows, complex political and economic factors came to bear on the reshaping of each colony's environment and the urgency placed on disease control.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Epidemics, Empire, and Environments by Michael Zeheter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & 19th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

FIRST ENCOUNTERS

CHAPTER 1

STRATEGIES OF TREATMENT

MADRAS, 1818–1833

Among Europeans, India—and the tropics in general—had an unflattering reputation for being unhealthy. Medical experts deemed the subcontinent’s climate to be especially harmful for Europeans, and surgeons had been warily observing the environment there ever since the British had arrived. The emergence of cholera as a recurring threat to individuals and the public during the second decade of the nineteenth century sharpened this negative view in all parts of British India. The disease forced the colonial authorities and their medical experts to turn their attention to the local environment they inhabited, as was the case in the city of Madras. Although the colonial state was weak and unprepared for such a challenge, it invested not only in the medical treatment of patients but also in the observation and analysis of the urban space. By doing so, it tried to identify the environmental features causing the disease in order to better understand the workings of cholera and possibly be in a better position to control it in future epidemics.

THE CITY OF MADRAS

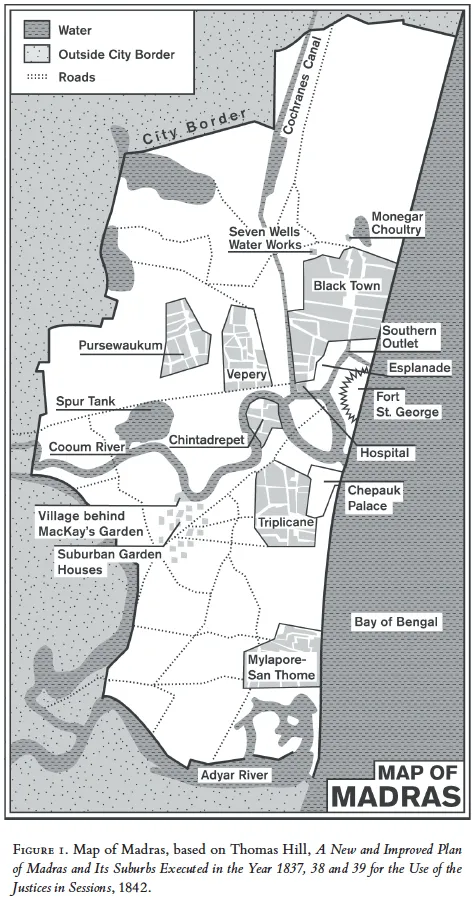

Madras was the capital of a vast province that had come into being only in the last years of the eighteenth century. In the early nineteenth century, Madras was a city of contradictions. Even to call Madras a city was at this time rather controversial, as its territory comprised densely settled towns, agricultural villages, fields, gardens, and water tanks. Travelers from Europe in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries questioned whether “city” was an appropriate name for the odd and amorphous agglomeration of settlements that was Madras.1 It was a British creation, inhabited mainly by Indians but ruled by a man whom a London-based corporation had appointed. Recently introduced European institutions coexisted with traditional Indian ones. As a port city, it was a major entrepôt where goods from Europe and Asia were exchanged, but it lacked a harbor. Madras defied all definitions save one: it was a colonial city.

Founded by the East India Company (EIC) in 1639 as a trading post on a flat, sandy beach on the Coromandel Coast just north of the mouth of the Cooum River, Madras was the earliest British territorial possession in India. The East India Company chose an auspicious location for its factory, protected as it was by Fort St. George. The company’s powerful rival, the Dutch Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, had no establishment in the vicinity, and the British had no trouble extracting territorial, judicial, military, and trade concessions from local Indian princes. The region produced profitable trading goods such as textiles, and an intensive coastal trade made available commodities from distant places. A regional surplus in agricultural production ensured supplies for the fort and provisions for the merchant ships’ long journey back to London around the Cape of Good Hope.2

The EIC established the city of Madras in a densely settled landscape of villages, towns, hamlets, fields, and water tanks that had been shaped over centuries. With the three square miles granted by the nayak of Poonamallee, the local prince, the company received three villages, along with the rights to settle and fortify the place and to trade in exchange for a yearly payment. Thus, from the very beginning, Madras consisted of several settlements.3 The commercial opportunities soon attracted Indians who would produce trade goods and supplies for the company. They were settled in the Black Town, so named in reference to its residents’ skin color. It was located to the north of the factory, while most of the British population preferred the protection of the fort, which was then also known as White Town.4

The Black Town was the center of Indian urban life in Madras. Home to more than one hundred thousand people circa 1800, it was as diverse a place as any. Portuguese, British, Armenian, and Jewish merchants had seized the opportunity to profit from intensifying trade. Seamen from China and Malaya arrived on the East India Company’s ships, and some of them stayed. Migrants from northern India, from the Deccan Plateau in central and southern India, and from the surrounding region settled there and often prospered. To minimize conflict among the many communities, the company directed them to settle in different streets, but otherwise it left daily administration and jurisdiction to indigenous elites. Only at the southern fringe of the Black Town, where private trading houses clustered in proximity to the fort, was there a substantial European presence. From their offices there, European independent merchants, Indian suppliers, financiers, and shopkeepers worked to profit off the East India Company’s trade and thus formed the backbone of the Black Town’s economy.5

By 1750, Madras had developed from an outpost to a colonial city-state that depended on a considerable hinterland for its supplies of labor, food, and trading goods—a hinterland that lay beyond the company’s jurisdiction. For its existence, the city relied on the cooperation of the nawab of Arcot, who ruled the Carnatic region as the mughal’s subordinate. Periods of conflict and peace alternated, but the nawab’s superior position generally remained unquestioned. It was only after the French Compagnie des Indes threatened to dominate southern India, thereby endangering the stronghold of Madras, that power relations began to shift in the East India Company’s favor. Victories in the ensuing wars between the EIC and the French and later against the rulers of Mysore, Haidar Ali and his son, Tipu Sultan, ensured English rule over south India for almost 150 years. The EIC thus gained considerable territory and indirect control over formally independent Indian states, including Mysore and Hyderabad. In 1801, the nawab of Arcot, already a dependent of the British, officially ceded the Carnatic to the company. When he gave up the remainder of his power in exchange for a yearly appanage, the EIC had finally acquired the city’s hinterland. Madras had developed from a city-state to the capital of a colonial state, or at least of its southernmost part.6

The territory of the city grew along with its political importance. By 1798, when its limits were determined for the next century, it covered more than forty square miles. Madras then consisted of the fort and the Black Town, as well as fifteen villages and numerous hamlets inhabited almost exclusively by Indians. Like the Black Town, those rural parts of Madras reflected the segmented character of the indigenous society, since the traditional rural landholding elite, the mirasdars, were concentrated in some of these villages. They derived their income from the labor of lower-caste tenant-cultivators—the parayars—who inhabited separate hamlets, or paracheris. Other, higher castes also formed their own villages. This social hierarchy was reflected in the city’s urban space, as the villages inhabited by higher-caste Indians occupied the more elevated spots of the generally flat territory of Madras, which protected homes from inundation during the rainy season. Although the paracheris were located on the best spots of the lower-lying spaces, the occupants suffered from the consequences of living in unhealthy, swampy, and poorly drained locations.7

The population of Madras grew, both by the acquisition of new territories during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and through the influx of parayar and lower-caste migrants who saw better chances of making a living in Madras. Thus, three of the villages in Madras quickly developed into towns with distinct characters: Chintadrepet, Triplicane, and Mylapore–San Thomé. The company founded Chintadrepet in the early eighteenth century as a weavers’ settlement to produce textiles for export to Europe. Located to the southwest of the fort across the Cooum River, Chintadrepet profited directly from the company’s commercial activities. Triplicane and Mylapore–San Thomé both predated the British presence on the Coromandel Coast. Mylapore had been a port since ancient times and, according to tradition, was associated with the martyrdom of the apostle Thomas in the first century. This legend attracted Portuguese merchants to the location. In the sixteenth century they founded a fortified town near the holy site, naming it after the saint, and erected the San Thomé Cathedral, where supposedly some of his relics were preserved. To the west of San Thomé the Kapaleeshwarar temple and its bazaar formed the center of Mylapore. The local mirasdars were traditionally responsible for the shrine and profited from trade with the pilgrims it attracted. Triplicane’s roots, too, could be traced back to a Hindu temple, the Vaishnava Parthasarathy, but the town’s growth gained momentum only when the nawab of Arcot chose the new Chepauk Palace as his permanent residence in 1768. His courtiers, soldiers, and officials settled in adjacent Triplicane, thus making for a significant Muslim population, the largest south of Hyderabad.8

Those towns, villages, and hamlets were interspersed with land used for agriculture, with extensive gardens and water tanks for irrigating the fields and supplying the livestock with water. Over the years of Madras’s growth, the villages lost some of their agricultural character. For the mirasdar elite, the profits to be made from agriculture paled in comparison with the money to be made from wealthy Europeans who purchased land for country houses outside the increasingly crowded fort. New high roads fanning out from the fort through Madras and into the colonial and commercial hinterland connected the villages with the urban, mercantile, military, and administrative centers, giving them an increasingly suburban character. Thus, the country houses were soon regarded as garden houses and became the permanent residences of most of the European elite of Madras, who then commuted to their workplaces in the fort or the Black Town.9

Garden houses became so popular that in some parts of Madras they almost completely squeezed out the Indian population and became “colonial enclaves,” to some extent reproducing in the suburbs the spatial segmentation of urban Madras into the Black Town and the White Town.10 Most Europeans and Indians lived separate lives according to their own rules in distinct spaces. The colonial government approved of this arrangement, which promised political stability by allowing the traditional Indian elites to maintain their social status and privileges. The European elites created their own distinct sphere in the fort and in the suburbs, where social events like dinners or balls took place. Only the wealthiest Indians in the company’s service could afford to imitate a European lifestyle and would be invited to such events. Europeans’ social contact with Indians and Indian culture was limited and strictly regulated, even in an occupational environment. Generally, Indians belonged to the realm of the subordinate, and the difference in status was emphasized.11

The less wealthy Europeans had to find a niche between the majority of the Indian population and the colonial elite. For most civilians, the rent for accommodation in the fort was increasingly prohibitive. They moved to the commercial parts in the south of the Black Town and along its waterfront, illustrating their orientation toward the sea and the fort. This proximity to Indian neighborhoods did not create a contact zone, however, as each community went its own way. By 1800, Fort St. George, once the location of European life and commerce in Madras, was the seat of the colonial government, and it accommodated a garrison of European troops.12

COLONIAL GOVERNMENT IN MADRAS

The East India Company in Madras—as in the rest of India—was hierarchically structured and gave all of its employees a rank that also determined their social status. Even the social positions of Europeans who were not in the company’s service—such as wives or independent merchants—depended on their relationship to the company. The governor ranked first. Appointed by the Court of Directors of the East India Company in London with consent of the Crown’s government, he was their representative and the highest official in the Madras Presidency but subordinate to the governors-general of India in Calcutta in matters concerning all of India, diplomacy, war, and peace. The governor of Madras had to report all dealings of the government to the East India House in London and also to Fort William. The distance from Madras to Calcutta and the even greater distance from Madras to London left the governor with considerable leeway and caused friction between both capitals throughout the nineteenth century.13

With the transformation of the East India Company from an armed maritime trading enterprise to a territorial state ruling millions of Indian subjects, the Madras Presidency required a more efficient and more professional government. The conduct of successful and profitable trading operations had lost its eminence. Military activity and the sound and efficient administration of the revenues collected from Indian taxpayers, which had become the company’s main source of income, were paramount, and the governor’s role and tasks changed accordingly. Most governors no longer rose through the ranks of traders but were recruited from the metropolitan elites even if they lacked personal experience with India. For governing the presidency, the governor could rely on the Executive Council. The presidency’s highest-ranking military officer, the commander-in-chief, was second in rank while the other councilors were promoted from the covenanted service. The councilors had considerable influence and power. In cases of emergency, the governor had the executive authority to override their opinions after consultation. When it came to daily business, legislative affairs, or revenue, however, he needed a majority of councilors on his side in order to govern.14

The governor-in-council ruled the whole presidency, including the city of Madras. No institutions represented the interests of the local population—Indian or European; local affairs were simply not a major concern for the colonial government. Before the late eighteenth century—when the East India Company’s dominance over India was secured—the government had left administrative and judicial matters to the various communities of the city’s population, including the Europeans. This policy of minimal political and judicial intervention was replaced by new institutions between 1792 and 1807, when Madras developed into the capital of an enormous colonial province, giving the government greater control over the population’s affairs. The Supreme Court was now the highest level of jurisdiction, ultimately deciding all civil suits regardless of whether Indian or European residents were involved. The justices in sessions, the assembly of the justices of the peace, assumed responsibility for the municipal affairs of the Black Town in 1793, forming the first civilian administrative body for any part of Madras. The rest of the city encountered the government mainly in the person of the collector of Madras, who was from 1802 onward responsible for revenue collections, overseeing the Hindu temples, and arbitrating caste disputes, thus acting as liaison to the indigenous communities and preserving the peace in all parts of the city.15 Essential for the success of these new governmental and administrative institutions was a new police force, which replaced the traditional indigenous office of the pedda naick in 1807. Under a superintendent of police with a staff of interpreters and writers, constables and peons patrolled the streets, kept the public peace, controlled the markets, and investigated crime.16 Thus, in less than two decades the foundation was laid for governing the presidency’s capital along the lines established in Europe.

Although the introduction of new administrative institutions strengthened the colonial authorities’ grip on Madras, their knowledge of the city in general was haphazard at best. Such a seemingly basic—and for administrative purposes, essential—fact as the size of the city’s population was uncertain and highly contentious. Despite some attempts to count the number of residents, there was no trustworthy census until 1871. Estimates ranged between 275,000 and more than 1 million. The Black Town alone was believed to have between 120,000 and 800,000 inhabitants. While one accounting by the police in 1822 came to a relatively low figure, many European residents and officials believed that their daily experience of a crowded “oriental” city contradicted these numbers. They estimated a minimum population of 600,000. Only the 1871 census eventually settled the matter by calculating the population to be under 400,000 and concluding that in the early nineteenth century it had been lower than 250,000 for all of Madras and approximately 100,000 for the Black Town. This wide range of estimates reflects the weakness of the young colonial state. Much of the information on which it operated was based more on anecdotes, guesswork, and impressions by the mainly European administration than on dependable data.17

The formation of administrative institutions was of course not limited to the capital. In fact, the governor-in-council headed a differentiated and complex apparatus consisting of several departments and boards that made it possible to govern the presidency. Since the East India Company had become the dominant power in India but lost its monopolies, matters of trade had lost their central status among its operations although the administration of supply, warehouses, shipping, and the like continued. From the mid-eighteenth century on, the company’s military and revenue administrations were crucial for the survival of the colony. They constituted the heart of a bureaucracy whose character was neither clearly civilian nor military, as the colonial state’s structure regularly encompassed both aspects of government simultaneously. Compared to the Military and Revenue Departments, however, others, such as the Judiciary or Public Departments, were less important, though also indispensable due to the responsibilities of territorial rule.18

COLONIAL MEDICINE IN MADRAS

The Madras Medical Service, the provincial unit of the Indian Medical Service (IMS), was certainly of great importance for the life of the colony. Though it could trace its roots back to ship surgeons on the first East India Company vessels that traveled to India, the Indian Medical Service was another component of the military operations that ensured the company’s dominance over India. From the 1740s on, military surgeons were hired from Europe in increasing numbers to care for the ever-growing armies employed by the company. After the conquest of Bengal, the prospect of continuing rule over a large territory required the maintenance of sizable armies, which meant that a continuous infusion of medical talent from Europe was needed to protect the troops from disease. This expansion of the need for medical care necessitated a more structured approach, and in 1763 Fort William established a medical service for Bengal. The other two presidencies soon followed suit. In the new Indian Medical Service a freshly recruited practitioner would start as an assistant surgeon and could later be promoted to surgeon and possibly end up as head surgeon. The surgeons’ main task was the medical care of both the European and the so-called Native troops. Most surgeons were assigned to garrisons and cantonments and went to other posts at...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Cholera and the Colonial State in Urban Environments

- Part I. First Encounters

- Part II. Integrating Sanitation

- Part III. Bacteriology and the Promise of Clarity

- Conclusion: The Colonial State and the Elusive Consensus Regarding Cholera

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index