- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

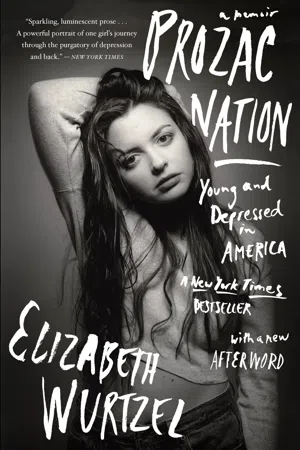

Elizabeth Wurtzel's New York Times best-selling memoir, with a new afterword

"Sparkling, luminescent prose . . . A powerful portrait of one girl's journey through the purgatory of depression and back." —New York Times

"A book that became a cultural touchstone." —New Yorker

Elizabeth Wurtzel writes with her finger on the faint pulse of an overdiagnosed generation whose ruling icons are Kurt Cobain, Xanax, and pierced tongues. Her famous memoir of her bouts with depression and skirmishes with drugs, Prozac Nation is a witty and sharp account of the psychopharmacology of an era for readers of Girl, Interrupted and Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar.

"Sparkling, luminescent prose . . . A powerful portrait of one girl's journey through the purgatory of depression and back." —New York Times

"A book that became a cultural touchstone." —New Yorker

Elizabeth Wurtzel writes with her finger on the faint pulse of an overdiagnosed generation whose ruling icons are Kurt Cobain, Xanax, and pierced tongues. Her famous memoir of her bouts with depression and skirmishes with drugs, Prozac Nation is a witty and sharp account of the psychopharmacology of an era for readers of Girl, Interrupted and Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Prozac Nation by Elizabeth Wurtzel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Literary Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

7

Drinking in Dallas

I started out on burgundy

But soon hit the harder stuff.

Everybody said they’d stand behind me

When the game got rough.

But the joke was on me.

There was nobody even there to call my bluff.

I’m going back to New York City.

I do believe I’ve had enough.

—Bob Dylan, “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues”

Summer of 1987. Dallas, Texas. The Oak Lawn section, to be precise. I have finished my sophomore year at Harvard. Somewhere down the road I managed to pick up the 1986 Rolling Stone College Journalism Award for an essay I wrote about Lou Reed for the Harvard Crimson, and now I have a summer job at the Dallas Morning News as an arts reporter.This is exactly where I want to be: I have been enchanted with Texas forever, or at least ever since I first visited all my cousins down in Dallas when I was still a little kid. To me, Texas is big strong men in cowboy boots, rugged Thoreauvian individualists, mining for oil as if it were gold, which it kind of was at one time. And Dallas is just the commercial center of all that wildcat fuel, one big country club in one sprawling suburb where all the boys play football and all the girls dream of growing up and having plastic surgery. Brawny brothers and silicone sisters everywhere. I’m not crazy about that part of the culture, all the materialism and wealth worship, but I go to Dallas thinking it will be good for me: Untrammeled capitalists are too busy making and spending money to be bothered with melancholia. Dallas, I believe, will be so vibrant, so spanking new, so urban-cowboy rowdy, so much the opposite of everything I associate with depression, so much brighter and shinier than all the dull darkness of the Northeast.

Of course the reality when I arrive in Dallas is quite a bit different. There is an oil glut, a concomitant real estate glut, the economy is depressed (not as bad as Houston, everyone points out optimistically), and Big D is in kind of a sorry state. Texas, in general, is meant to be rich, its entire culture is about good old boys making it big quick, and Texans, particularly those in Dallas, don’t seem able to handle poverty gracefully. They still buy Baccarat crystal at Neiman Marcus on Saturday, even if they just laid off two hundred of their company employees on Friday. It’s like watching a grown man who’s too proud to cry, who is desperately stifling his tears, cry anyway.

Every house I pass seems to have a FOR SALE sign in front, every apartment complex has a FOR RENT: ONE MONTH FREE! placard posted at the entrance, and along the highways there are tons of half-completed skyscrapers, pink granite and silver glass affairs conceived in times of prosperity, which are never going to be finished. Cranes and rubble everywhere: They used to say that the Dallas mascot was a crane opening its jaw to the blue skyline. This is nothing like the city I saw when I was visiting my relatives who live in North Dallas during the Republican Convention in 1980.

Dallas in 1987 is depressed and depressing.

Still, I am mysteriously happy here, at least at first. I live in this grand and dreamy apartment that I’m subletting from a city desk reporter who is trying to cohabit with her boyfriend. From the first time I looked at the place—which is only $300 a month, even less than my weekly salary—I thought it was the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen, with French doors, a ceiling fan, a little porch lush with plants and flowers and greenery and a cast-iron and glass breakfast table, and the sort of vast, open kitchen area with blue and white Mediterranean tiles that made me want to put small spice plants and ivy by the sink and hang chimes by the window. The bathtub even had little feet, and its edges curved out like cappuccino froth overflowing a mug. I’d be living alone for the first time in my life, like a big girl, and I felt a certain joy at the idea of moving in. I kept walking through the rooms of this charming railroad flat, and thinking to myself, This will be mine, this will be mine, all mine. I felt like Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, the independent gal in New York beaming to be on her own, smiling all the time as she strolls down Fifth Avenue; or like Mary Tyler Moore throwing her hat as if it were caution to the winds of Minneapolis.

I love the apartment so much that sometimes I just want to roll around on the hardwood floors with rapt delight.

And much to my surprise, there’s even kind of a counterculture in Dallas, a small one, but enough to entertain me for the summer. I end up spending a good deal of time in Deep Ellum, a warehouse district on the eastern edge of downtown where artists and musicians live in lofts with exposed pipes and whitewashed brick walls, where rock clubs are as spartan and vast as airplane hangars and all you can get to drink in them is beer in a can, where you can catch groups like Edie Brickell and New Bohemians playing outdoors at Club Dada once or twice a week. Deep Ellum seems so vital to me that it’s almost corny. Here young people are trying to build a scene from scratch and live in an alternative way as if it were something brand-new. Which for them, of course, it is. Down in Deep Ellum, it’s a bit like being lost in the sixties, not because all the kids who hang out there idolize or idealize that era and bring it back with retro touches, but because the Kennedy assassination so paralyzed the city that the sixties are hitting Dallas twenty years late.

I could have been happy in Dallas. Except for the car problem.

Having grown up in New York, I never learned how to drive, and the lessons I took in Cambridge in preparation for the summer didn’t end up helping much when I slept through my road test. Without a driver’s license, without a rental car, and without access to anyone else’s car, I was going to have to do a lot of transit negotiating that summer. The Morning News would pay for my cabs when I was on assignment, but otherwise I would pretty much be at the mercy of strangers. I would have to schedule all my activities around other people. I would always leave things I enjoyed early or stay somewhere miserable late because I needed to go with my ride. I could never just run home for five minutes to change clothes or grab something the way anyone with a car could, so I had to plan my days carefully.

It sounds like a small price to pay, but that summer I came to understand why teenagers all over America associate a driver’s license with freedom. I understood that without a car, I was basically trapped in Dallas. And when the big bad downs started kicking in, as I should have known they inevitably and eventually would, I’d find myself scared to death, alone in my apartment, with no way out.

For all of June and a lot of July, I was convinced that everything was really okay for the first time ever. I even started to think that I had recovered from my depression, that all I had ever really needed was a satisfying job that kept me busy, that all this sitting around and intellectualizing and analyzing and hypothesizing and contemplating and explicating and prognosticating all the time was the source of all my problems. Semiotics, not a chemical imbalance, was killing me. I just needed to stop thinking so much and start doing.

I wrote like crazy, at least two or three reported pieces a week, sometimes more. I wrote like my life depended on it, which it kind of did. My editors were mystified by my productivity, thought I was mainlining copy or something. They rewarded me by letting me write odd and unconventional essays about art and feminism and Madonna and Edie Sedgwick, or anything else I could come up with, and then they’d stick them on the front of the Sunday section. They nominated me for awards from the Texas Newspaper Association and the Dallas Press Club. They paid for my overtime, which added up to so much money that I was practically doubling my salary (and it was costing them so much that after a while the assistant managing editor who oversaw my section of the paper suggested I take some comp days instead). My editors were pleased with my work and I was extremely prolific and conscientious. So they kind of let it slide when I started to crack.

Cracked in little ways. Walked into work at three in the afternoon on the grounds that I had to do some reading at home. Or had been up all night watching bands at the Theatre Gallery and couldn’t function on no sleep. All of which was perfectly legit, no problem, my editor would say, so long as I didn’t have to be in to go over some copy that day. But then, when I did arrive at my office, I spent most of my time returning personal phone calls or telling the other reporters about the latest man in my life, an ever-changing array of cowboys, restaurateurs, musicians, and college sophomores. I’d tear through them with such alarming alacrity that after a while I was dating brothers, cousins, entire families, it seemed. I found this all very amusing. I’d just blab and blab. People would look kind of entertained but mostly bewildered as if to ask, Why is this girl telling us all this stuff? This is an office, people are trying to work, I think they sometimes wanted to say.

But no one really cared. I managed to meet all my deadlines, my work was always good, and, they figured, she’s young, she’s from up north where people chatter, no harm done. Even after everyone else left the office at 6:00, I would still be there for hours getting my pieces done since it was impossible for me to work when there were people around to talk to. Between so much writing and so much chatting, my weeks were too packed for me to notice my emotional state at all, except in passing blinks of fatigue.

But on weekends, with no exigencies of the moment beckoning at my head, I realized that I was all alone in the great state of Texas and all alone in the world. Even the brief, two-day gap in activity was enough time for that old ugly feeling, that familiar black wave, to start creeping up on me, threatening to drag me away. Since I slept so little Monday through Friday, you’d have thought that I’d appreciate the days off to catch up, but I could barely sleep anyway, and my nights passed fitfully. I was tired all the time, but unable to find relief. It was like being on cocaine after the trippy effect has worn off and all that’s left is a wired feeling that keeps you staring at the ceiling all night, unable to doze. The only difference was, this was not the aftereffect of some coke—this was me. So I filled up the hours as best I could. No one else wanted to surrender a Saturday to cover a day of heavy metal that was known as the Texxas Jamm, so of course I expressed my willingness to review Poison, Tesla, and the rest of the motley assortment of bands that would be playing at the football stadium. No one else wanted to spend July Fourth in Waxahachie at Willie Nelson’s Picnic, so I did my civic duty and accepted the assignment. Pain in the ass though I was, who could really fault a girl who’d saved them from having to cover these tawdry and embarrassing bits of Texas culture that only a Yankee could appreciate?

To a certain extent, anyone who’s alone and new to an area would be inclined to do a lot of running around, and at first I thought all my manic energy was the result of simple curiosity and the novelty of Dallas. But I was hardly a stranger in a strange place: I’d spent a lot of time in Texas when I was growing up, I’d traveled from one end of the state to the other, I had family in Dallas, I knew the town pretty damn well, and I could very easily have spent weekends in the peaceful company of my relatives, eating barbecue and going to the mall. Sometimes I did do that. But it was never pleasant for me. I was so nervous all the time, always feeling like there was something I should be doing but wasn’t, always feeling at the mercy of something that felt like a hive of bees buzzing in my head.

Once I woke up at three in the morning, but without my glasses on I mistook the three on my digital clock for an eight. In fear of being late for—for whatever—I charged out of bed, jumped in the shower, dressed, made myself up, drank coffee, and ate Cocoa Krispies, and only as I grabbed my handbag to walk out the door did I notice that the sky was dark, it was the middle of the night, there was no need to rush. And it’s not exactly like I had to punch a time clock. When I got back into bed, I laughed to myself a little bit, and then I just thought, This is crazy. What’s happening to me? I’ve got all this energy, not the refreshing, delightful kind but the edgy anxious type, and not a damn thing to do with it. If the editors of the Dallas Morning News decided one day that I had to write the entire contents of the newspaper by myself, I still wouldn’t be busy enough to satisfy this enormous, deleterious need I have to keep moving. There will always be this deficit, this flabby remainder of self hanging over me, demanding more attention than I and seventy-two other people put together could possibly satisfy. What I wouldn’t do to be Alice climbing through the looking glass, taking one of those pills that makes you small, so small. What I wouldn’t do to be less.

And I started to think, Damn, I need medicine. I need something reining in all this thinking. Because I’m going to go crazy like this. I was almost twenty years old, which is often the age that people with bipolar illness experience their first manic episode, so maybe that’s what was happening to me. When I wasn’t working, I was out partying, dating sixteen different men at once, never sleeping at night, gulping Jolt cola and snorting speed for breakfast so I could get through the rest of the day. I figured out that I could manage my moods fairly well if I stuck to a rigorous chemical routine of beer and wine in the evenings, followed by mornings of major uppers.

Drinking in Dallas was a lot more fun than it had ever been anywhere else, although I couldn’t say why. Perhaps it was because I took to hanging with some hard-news reporters who tended to hard-drink with relish. In fact, to talk to them, you’d almost think that alcoholism was the sign of a journalist doing his job well, a sign of someone who’d seen the blood, the white outlines, the body bags, all the gore of a triple murder, and drank to clear his head of all the ugly he was forced, and perversely delighted, to see. But the variety of alcohol-related experiences also excited me. At the time, Corona beer was available only in the Southwest, and having a bottle with a lime squeezed into it was such a novelty to me, a brilliant admixture of a real drink and a simple brew. Boilermakers—a shot of bourbon, preferably Maker’s Mark, quite literally thrown glass and all into a stein of beer—were another new discovery. Getting ahold of some speed—whether it was methamphetamine or Dexedrine or Benzedrine—was a pretty easy task because the drug scene in Dallas was so clean-cut. It seemed like everyone lived next door to some nice collegiate dealer who was putting himself through Southern Methodist University selling plants, pills, and powders, or knew someone else who did. But usually all it took was all the caffeine and sugar provided in Jolt to get me through the day, so the cycle of up and down could be maintained cheaply and legally.

One night, I planned to interview the Butthole Surfers after they played a gig down in Deep Ellum. As it happens, they were leaving for a European tour the morning after they played Dallas and decided that rather than get only a couple of hours of sleep after the show, they’d just not sleep at all. So I stayed up with them, smoking their weed, sipping on Coronas with lime, hearing stories about their pit bulls, hearing about how they had an indirect sexual encounter with Amy Carter by rubbing their private parts on her suitcase when they played at Brown University, hearing about how one of their former drummers is now a bag lady living in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, hearing about how they got the name the Butthole Surfers, and realizing that these guys were the real-life embodiment of the movie Spinal Tap. I learned that they had once been called the Winston-Salems and now occasionally played local bar gigs under the name the Jack Officers.

I was so amused that I just kept getting more and more stoned and drunk, and the last thing I remember before I went home to shower and change my clothes so I could go back to the office is standing behind the club, in a back alley, talking to the guitarist, who was, I thought at the time, the cutest thing alive, with sweet brown eyes and a compelling smile, the combination of which, when he looked at me so directly and soberly even though he’d smoked even more pot than I had, made me want to do anything, anything for him. Never mind that I was feeling stoned and sensual and dying to take all my clothes off, even back there, standing next to the junkyard, the site of new construction, part of the gentrification process, and surrounded by nothing but the night. We started to kiss, his shirt came off, and pretty soon his hands dug under my blouse, rubbing my breasts as his finger made circles around my nipple. And I reached into his pants, touched him, touched his half-flaccid penis that got harder as I held on to it, and suddenly I realized that I didn’t want to do this.

It hadn’t even been a year since I lost my virginity to a recent Yale graduate who I’d met at the Rolling Stone College Journalism Award luncheon. It hadn’t even been a year since I decided that my mouth was getting tired and chapped from giving so many blowjobs, that it was time to start having sex like a normal nineteen-year-old. It hadn’t even been a year since my complete initiation into sexual activity, and I was not ready to start screwing around with a virtual stranger—with whom, I might add, it was unethical for me to be carrying on—in some Dallas back alley. Somehow, I had this moment of truth, and I felt certain that I didn’t want this, didn’t want to live this life, had to get out of there right then. So I pulled my hands away from his fly, pulled my shirt back on, and started to run, but the thing was, I couldn’t run anywhere. I had to call a taxi first. And I thought to myself, You know this sucks. It sucks when you can’t make a clean getaway.

And I felt that something was very, very wrong. What had I wanted from that guy, anyway? Why had I led him outside in the first place? This seemed to be a routine for me, getting started on sexual encounters and not only stopping them, but actually fleeing from the room as if in shame or in danger, realizing that I just don’t want to be there, that I felt trapped and cramped. I wanted so badly to lose myself in sex, to be thoroughly slutty and have one zipless fuck after another. I wanted to be a wild thing. But in the end, I couldn’t ever go through with it because it’s never like that, there was no pleasure for me in being an easy lay. Fast, cheap sex was no fun at all. My body and mind are just too complicated. I’d seen movies like 9½ Weeks, and I envied the Kim Basinger character and the way she could achieve a full—even multiple—orgasm while standing in the rain with her back against a brick wall in a dark cul-de-sac as street thugs chased after her and Mic...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Contents

- Copyright

- Author’s Note

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Prologue: I Hate Myself and I Want to Die

- Full of Promise

- Secret Life

- Love Kills

- Broken

- Black Wave

- Happy Pills

- Drinking in Dallas

- Space, Time, and Motion

- Down Deep

- Blank Girl

- Good Morning Heartache

- The Accidental Blowjob

- Woke Up This Morning Afraid I Was Gonna Live

- Think of Pretty Things

- Epilogue: Prozac Nation

- Afterword (2017)

- Acknowledgments

- Credits

- About the Author

- Connect with HMH