![]()

DEFINITION AND CONTEXT

Truly new ideas are rare but when one comes along it can start a revolution. We are at the frontier of one of these revolutions today, the techno-textile revolution, the convergence of textiles and technology.

The materials that you will be introduced to in this book will challenge your idea of what fabrics and textiles are and inspire you to rethink what your clothing and other products made with textiles can do.

Fabric is our second skin. We each have a deep personal connection to it from the time we are born. Every day we expect the fabrics that touch our bodies to keep us warm or dry, to be soft or strong, to be flexible or give us support and many other things. At the same time, we demand that our products and clothing perform many of these functions while maintaining their shape and color and expect that they will be easy to care for and to clean. We use textiles in our environments and to build with, we use them in manufacturing and require that they be sustainable, renewable, and use little energy. The more advanced textiles become, the more we demand of them. Textile and material science is constantly developing ways to meet, exceed, and even anticipate our demands as consumers and users.

The pioneers of this field explore the next frontier of these technological developments in materials, fibers, fabric construction, and chemical finishes.

Interview: Melissa Coleman

New media artist, lecturer, blogger, and curator of “Pretty Smart Textiles” and three smart textiles exhibitions, Melissa Coleman has her pulse on the future. Her works are critical explorations of the body in relation to technology. She writes for Fashioning Technology and has taught at art and design schools in The Hague, Rotterdam, Tilburg, and Eindhoven.

I interviewed Melissa to get her perspective on the difference between smart textiles and e-textiles and what she thinks are the most exciting things that are happening in smart textiles today.

RPF: Can you give me a simple definition of e-textiles and the difference between smart textiles and e-textiles?

MC: E-textiles is a name for textiles that integrate electronics in the textile itself. In its most perfect form, which doesn’t really exist yet, you might not even be able to tell the difference between a regular textile and an e-textile because the electronics are physically part of the textile structure. At the moment this is mostly happening in the form of metal-coated textile fibers. But people are also experimenting with fibers that can generate electricity through movement, or through the sun. Smart textiles don’t describe the material as much as its innovative character. In some cases this might mean a highly technical nano-coating, in other cases it might mean the textile has integrated electronics and a computational function. Really all the “smart” part describes is that it has more functions than a traditional textile.

RPF: From your perspective, what do you see as the most exciting things happening in smart textiles since you curated “Pretty Smart Textiles”?

MC: Well, there are two works that I think are particularly interesting because of what they suggest in terms of future visions. One work is by Jalila Essaïdi, she’s a Dutch artist and curator who founded the BioArt Laboratories in Eindhoven. One of her works, 2.6g 329m/s, involves integrating spider silk into human skin. Spider silk thread is much stronger than steel and if we were to get such a skin transplant—or if our bodies could produce it—we could potentially resist the impact of a bullet. She created a little patch of human skin with embedded spider silk, and when a bullet is fired it bounces off it, so it’s actually a tiny bit of bulletproof skin. There are still problems in making it work in the long term in a real living body, but I like to think that’s just another technical problem to be solved. This project’s main function, in my opinion, is not making this work but in showing that it might work. This triggers the imagination. What do we want to become if we can make technology integrate with us on the most intimate levels?

The Holy Dress, by Melissa Coleman in collaboration with Leonie Smelt, is a garment that trains you to be a better person. Using a speech recognition system and voice stress analysis, the dress starts to glow and increases in intensity as the likelihood of a lie is detected. When it guesses that a lie has been told, it lights up fully and then flickers as it delivers an electric shock to the wearer as punishment for the lie. For the wearer of The Holy Dress, technology performs the function of religion, helping the wearer live an honest life.

RPF: That sounds really interesting.

MC: It is super interesting. I think, even though it’s such a small patch it suggests so much. It just breaks open the idea of what our skin could be once we start manipulating it in all kinds of ways. What’s funny is that she never considered it a textile until other people started calling it that. For her it was much more about specific augmentation of the human body. But I think for people who are interested in textiles the two are closely connected. Clothing is sometimes called our second skin. To me this project suggests a merging of our first skin that we were born in, and this second skin that man created.

RPF: And the other work?

MC: This work is by Ebru Kurbak and Irene Posch called Drapery FM. It’s a material exploration into how you could incorporate electronics in the structure of a textile. I think the original idea that they started with was political where they were trying to make sweaters that would be able to do peer-to-peer communication so that you could exchange data on a highly personal basis.

In the end they made a knitted fabric that functioned as a radio. You could tell the different electronic components (resistors and capacitors) apart because they used different colors of thread that had a metal thread in the twining. The innovative aspect was mostly in creating textile capacitors through knitting. There’s a fortunate coincidence where the way the knitted textile is built up through loops sort of matches the way an electronic capacitor works. So they were able to make really seamless electronics. The beauty is in how much it is still textile and how much it works as a piece of electronics. That works on the imagination in a very different way.

RPF: All of these artists seem to be working in an area that questions where our bodies end and technology begins. Is this a theme you see fine artists who work with smart textiles exploring?

MC: One of the functions of fine art is to create a discourse around subjects that are already happening in society, or that are looking to start happening. And anything related to textiles is never separated far from issues around the body. When you start combining textiles and electronics it touches on issues around privacy, intimacy, expression, and different forms of display. It makes sense to me that fine artists would be interested in this medium because it’s a very suitable medium to discuss these topics.

RPF: I can see that using smart textiles and wearable technology can be a great way to visually show what your body is doing in a way that you wouldn’t necessarily be able to otherwise.

MC: Yes, it’s a lot about identity and the personal aspects of technology. I think that technology, even though a lot of it’s happening online in a global semi-public space, is becoming hugely personal as well. It’s that strange thing where technology makes space, time, and social context irrelevant to some degree. The borders between public and private are also blurring significantly. Who knows, it may yet get to the level where we will literally want to share everything about ourselves.

RPF: Which media art organizations in the Netherlands do you recommend following?

MC: V2_Institute for the Unstable Media and Mediamatic have been instrumental in popularizing e-textiles and wearables in the Netherlands over the last ten years. But it’s not just media art organizations anymore. A lot of interesting things are happening in universities and art and design schools in The Netherlands. Eindhoven University of Technology even has a part of their industrial design program especially dedicated to it, called Wearable Senses.

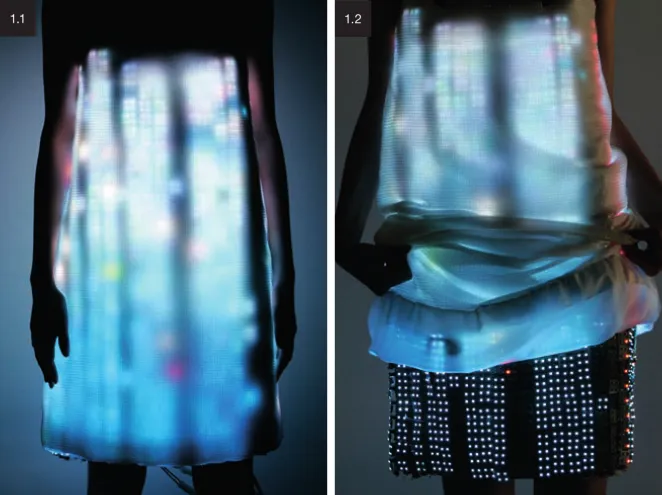

1.1 & 1.2

London-based designer Hussein Chalayan collaborated with Swarovski AG to create a collection of dresses that used LED lights and lasers to explore the electrical nature of the human figure.

The Second Skin

What makes smart fabrics revolutionary is that they have the ability to do many things that traditional fabrics cannot, including communicate, transform, conduct energy, and grow. Think of the body as a communication device. Our five senses are the input and output tools; they are how we give and receive information about what is happening inside our bodies and outside in our environment. Our garments interact with all of our senses; they are seen, heard, felt, smelled, touched, and may even be tasted. Smart textiles join these phenomena by using our senses as a way of gathering information from and about us by means of pressure, temperature, light, low-voltage current, moisture, and other stimuli.

Some smart textiles also have the ability to gather this information from our ...