![]()

PART I HISTORICAL CONTEXT OF MATERIALS AND INTERIOR DESIGN

1. THE INDUSTRIAL AGE: DESIGN MOVEMENTS AND THEIR MATERIALS

2. THE EVOLUTION OF MATERIALS

3. THE HISTORICAL INFLUENCE OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL AGENDA AND ITS IMPACT ON MATERIALS

4. THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

![]()

1. The Industrial Age: Design movements and their materials

The Industrial Revolution in Europe and America transformed methods of production and the use of materials in product, furniture, and interior design. Manufacturing processes became increasingly mechanized, coal-fueled steam power was adopted (replacing water mills, humans, and animals as the primary source of power) and transportation improved, giving industries access to a plentiful supply of minerals and raw materials. These changes were particularly significant for iron and steel production and also the textiles industry, which increased its capacity to produce a diverse range of fabrics for different applications; the quest for wholly man-made materials (synthetics) can also be traced back to this period.

The Industrial Revolution led to a shift away from the handcrafted product to mass-produced goods such as ceramics, furniture, carpets, and other domestic objects. The production of wallpapers and textiles for curtains and upholstery, formerly hand block-printed, was transformed by mechanization and the invention of cheap aniline dyes1, which replaced the natural pigments extracted from insects, leaves, and flowers. These changes allowed wallpapers and textiles to be produced in abundance and in a kaleidoscope of colors and patterns.

During this period standards of living were rising and the middle-class consumer emerged with the income to invest in the design of their domestic interiors, following fashionable trends and often adopting a style that emulated the homes of their social superiors.2 Items that had previously been regarded as luxurious were viewed as necessities, and an era of mass consumerism and the quest for instant gratification began. The populace was enthralled by the novelty of abundance,3 and industry now had the potential to deliver good and affordable design to a mass market.

Another significant change triggered by the Industrial Revolution was artificial lighting. In the age of candlelight and gaslight (introduced into homes in the Victorian era) dark materials were selected to mask the dirty marks left by flames, and reflective materials, gilt, and mirrors were used in interiors to enhance the effect of the lighting. By the end of the Victorian period, electric light was used in many homes and this changed the functionality and aesthetic qualities of some of the materials selected.

The Tea, oil on canvas, c.1880, by Mary Cassatt. A depiction of a middle-class interior furnished with the products of the Industrial Revolution: mass-produced textiles, wallpapers, crockery, and silverware. (Photograph ©2012 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.)

Not all designers and commentators of the period embraced these changes. John Ruskin (1819– 1900), a very influential artist, poet, and critic, lamented the shift away from craft production and considered it to be dehumanizing and immoral:

It was Ruskin’s bitter denunciation of the design of industrially produced objects that impacted most strongly on the Arts and Crafts movement. The assumption that machine-made things would inevitably be tasteless and garish led to advocacy of a return to hand craft as the only possible route to reform.4

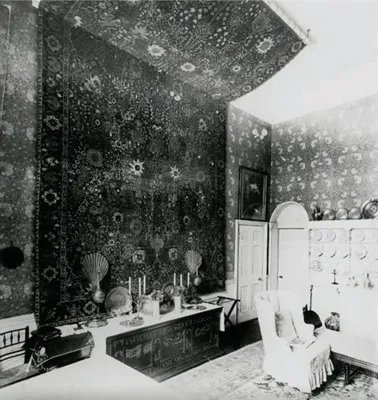

The Arts and Crafts Movement was founded by William Morris (1834–1896) a writer, designer, and socialist. He believed in the intrinsic value of handmade products, which, unlike mass-produced artifacts, are imbued with the mark and mind of their maker. He established Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. with partners including Edward Burne-Jones and Dante Gabriel Rossetti; this company became Morris & Co., makers of hand-printed textiles and wallpaper that are still available today. The handcrafted approach to the use of materials can be seen in the design of Morris’ own home, Kelmscott Manor: hand-printed wallpaper; richly colored and decorative handmade rugs as wall hangings—the mark of the carpenter, the metalworker, and the upholsterer are all visible. Stylistically and philosophically, the Arts and Crafts Movement had much in common with the Gothic Revivalists, including a tendency to look back to and romanticize the past.

William Morris’ preference for the handcrafted is evident in his own home, Kelmscott Manor, Gloucestershire, England.

The dark stained wood used in Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s Glasgow School of Art, Scotland, has a handcrafted quality.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868–1928) was a Scottish architect and designer known for his architecture, interiors, and furniture designs. He inherited some of the traditions of the Arts and Crafts Movement, evident in his highly crafted use of materials in projects such as Hill House in Helensburgh, 1902, and the Glasgow School of Art, 1907–9. However, having traveled in Europe he was also influenced by and was a proponent of the Continental art and design movement, Art Nouveau, which grew in the 1890s.

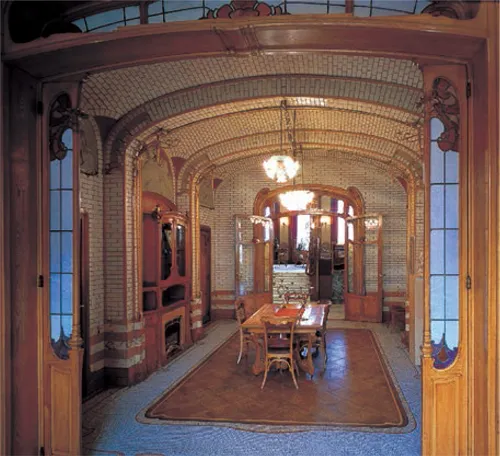

Art Nouveau advocated an interdisciplinary approach to design, with artists, designers, and architects working collaboratively on fully integrated interiors and architecture (an approach that can be observed in many design practices today). Its exponents embraced some of the changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution, particularly the production of new materials:

The progress made in iron construction during the second half of the nineteenth century is crucial for the development of the Art Nouveau interior. ... The early Art Nouveau’s frank exposure of metal in the domestic interior had radical implications in the context of the traditional styles and materials used by Beaux-Arts architects.5

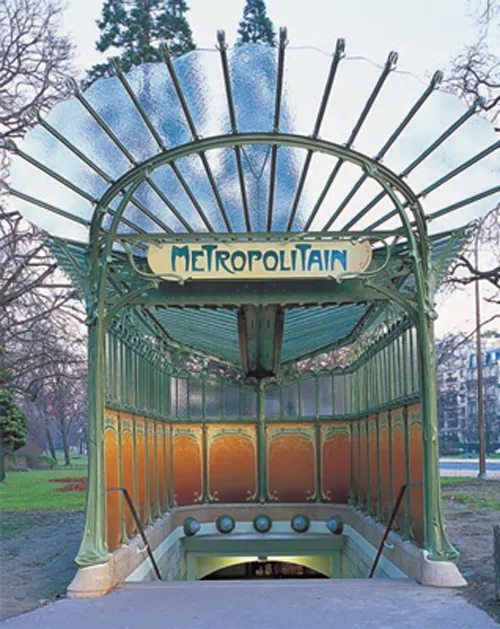

In 1862, at the London International Exhibition, European artists and designers were exposed to a significant collection of Japanese art and artifacts including lacquered woodwork, woodcuts, prints, and textiles. Although Japanese art and design had long since been influential in the West, this exhibition (and Japonisme in general) had a significant impact on the artists and designers of the period and also those of subsequent generations, such as Eileen Gray (1878–1976) and Aubrey Beardsley (1872–98). Beardsley’s use of fluid line and composition clearly references the art of Japan, and in turn his work was inspirational to leading designers of the Art Nouveau movement—for example, Victor Horta in Belgium and his use of exposed, decorative metalwork and vegetal forms; and Hector Guimard in France, famous for his designs for the Paris Métro. The Art Nouveau designers used materials to create organic forms and highly decorative, patterned surfaces, rich in color and texture.

As well as being influenced by European design, Charles Rennie Mackintosh had a significant influence on the Vienna Secessionists. The Secessionists were keen to break away from established practices and traditions of art and architecture in Austria, and like the Art Nouveau designers they blurred “professional” boundaries and aimed to unite the arts: painting, design, architecture, and music. Like the practitioners of the Arts and Crafts Movement, they had a preference for good-quality handcrafted fixtures and fittings, and artwork that was integrated in order to create holistic and decorative interiors.

The woodwork of the dining room at the Victor Horta Museum, Brussels, exemplifies the distinctive organic forms of Art Nouveau.

Hector Guimard used decorative ironwork and glass to create the distinctive vegetal entrances to the Paris Métro.

In 1917, a period influenced by the emergence of the Modernist movement in architecture and Art Deco, Eileen Gray designed the interior for the rue de Lota apartment. She conceived all the interior elements—the rooms, the furniture, and the products—creating a hybrid of Modernist and decorative approaches to design. She furnished the apartment with her own products, including her Pirogue Chaise, Serpent Chair, and lacquered Block Screen (she had learned how to use Japanese lacquering techniques). Other items of furniture were also designed by Gray for this context, resulting in a cohesive “whole”; this interior, along with her other work, had a significant influence on her contemporaries and future generations of designers.

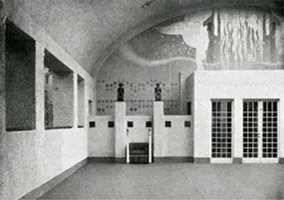

Architects, artists, and designers collaborated on the design for the XIV Secessionist Exhibition interior, Vienna, 1902. Gustav Klimt’s frieze, which was painted directly onto the walls, can be seen in the background.

The use of materials in Eileen Gray’s rue de Lota apartment in Paris bridged Art Deco, the Moderne, and Modernism. This image shows the apartment after a refurbishment in 1930 by Paul Ruaud; her Pirogue Chaise can be seen on the left.

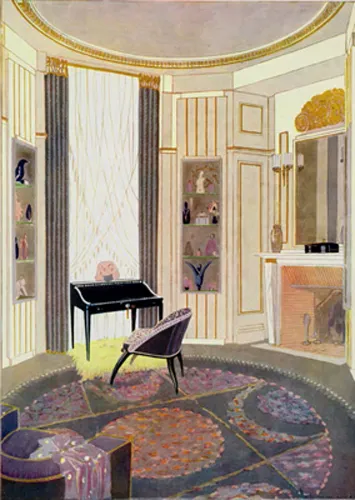

A designer of furniture and interiors, Emile-Jacques Ruhlmann was influenced by Art Nouveau, the Arts and Crafts Movement, and eighteenth-century furniture. He used opulent materials, particularly rare woods, as illustrated in this 1926 watercolor of an interior.

The Art Deco movement gained recognition in France in the 1920s, and grew to have an influence on international art and design—particularly in the UK and America. Art Deco referenced a diverse range of design influences, from African art, Aztec designs, and Egyptian art and design. In 1922 Howard Carter unearthed the tomb of Tutankhamen, and this gave a significant stimulus to the public’s interest in Egyptian styling, a fashion adopted by Art Deco designers: cinemas, factories such as the Hoover Building, and furniture were “Egyptianized.” Opulent, rare, and ostentatious materials such as inlaid mahogany and ebony, real animal furs, and highly lacquered finishes were combined with more modern materials such as aluminum and Bakelite, the first mass-produced plastic.

The Deco style was interpreted for Hollywood film sets, for example in the designs of Cedric Gibbons for films such as Grand Hotel (1932) and Born to Dance (1936); Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927); and Darrell Silvera’s sets for Swing Time (1936). These glamorous films helped to internationalize and popularize the movement’s style, use of materials and decoration, which was then adapted for ordin...