![]()

Chapter 1

Reading for Meaning

Reading for Meaning in a Nutshell

Reading for Meaning is a research-based strategy that helps all readers build the skills that proficient readers use to make sense of challenging texts. Regular use of the strategy gives students the opportunity to practice and master the three phases of critical reading that lead to reading success, including

- Previewing and predicting before reading.

- Actively searching for relevant information during reading.

- Reflecting on learning after reading.

Three Reasons for Using Reading for Meaning to Address the Common Core

1. Text complexity. Reading Anchor Standard 10 and Appendix A in the Common Core State Standards for ELA & Literacy (NGA Center & CCSSO, 2010a) both call for increasing the complexity of the texts that students are expected to be able to read as they progress through school. Reading for Meaning builds in all students the skills used by proficient readers to extract meaning from even the most rigorous texts.

2. Evidence. The Common Core's Reading Anchor Standard 1 and Writing Anchor Standards 1 and 9 all highlight the vital role of evidence in supporting thinking. As the English Language Arts standards' (NGA Center & CCSSO, 2010a) description of college and career readiness states, "Students cite specific evidence when offering an oral or written interpretation of a text. They use relevant evidence when supporting their own points in writing and speaking, making their reasoning clear to the reader or listener, and they constructively evaluate others' use of evidence" (p. 7). Few strategies put a greater premium on evidence than Reading for Meaning, which provides direct, supported training in how to find, assess, and use relevant textual evidence.

3. The core skills of reading. Reading for Meaning helps teachers build and assess the exact skills that the Common Core identifies as crucial to students' success, including identifying main ideas, making inferences, and supporting interpretations with evidence. Because Reading for Meaning uses teacher-created statements to guide students' reading, teachers can easily craft statements to address any of the Common Core's standards for reading. See Figure 1.2 to learn how you can design statements to address different anchor standards.

The Research Behind Reading for Meaning

Reading for Meaning is deeply informed by a line of research known as comprehension instruction. Some scholars attribute the beginning of the comprehension instruction movement to Dolores Durkin's (1978/1979) study "What Classroom Observations Reveal About Reading Comprehension Instruction." Durkin discovered that most teachers were setting students up for failure by making the false assumption that comprehension—the very thing students were being tested on—did not need to be taught. As long as students were reading the words correctly and fluently, teachers assumed that they were "getting it."

Thanks in part to Durkin's findings, a new generation of researchers began investigating the hidden skills and cognitive processes that underlie reading comprehension. A number of researchers (see, for example, Pressley & Afflerbach, 1995; Wyatt et al., 1993) focused their attention on a simple but unexplored question: What do great readers do when they read? By studying the behaviors of skilled readers, these researchers reached some important conclusions about what it takes to read for meaning, including these three:

- Good reading is active reading. Pressley (2006) observed, "In general, the conscious processing that is excellent reading begins before reading, continues during reading, and persists after reading is completed" (p. 57). Thus, good readers are actively engaged not only during reading but also before reading (when they call up what they already know about the topic and establish a purpose for reading) and after reading (when they reflect on and seek to deepen their understanding).

- Comprehension involves a repertoire of skills, or reading and thinking strategies. Zimmermann and Hutchins (2003) synthesize the findings of the research on proficient readers by identifying "seven keys to comprehension," a set of skills that includes making connections to background knowledge, drawing inferences, and determining importance.

- These comprehension skills can be taught successfully to nearly all readers, including young and emerging readers. In Mosaic of Thought (2007), Keene and Zimmermann show how teachers at all grade levels teach comprehension skills in their classrooms. What's more, a wide body of research shows that teaching students comprehension skills has "a significant and lasting effect on students' understanding" (Keene, 2010, p. 70).

Reading for Meaning is designed around these research findings. The strategy breaks reading into three phases (before, during, and after reading) and develops in students of all ages the processing skills they need during each phase to build deep understanding.

Implementing Reading for Meaning in the Classroom

1. Identify a short text that you want students to "read for meaning." Any kind of text is fine—a poem, an article, a blog post, a primary document, a fable, or a scene from a play. Mathematical word problems, data charts, and visual sources like paintings and photographs also work well. The "Other Considerations" section of this chapter provides more details on nontextual applications.

2. Generate a list of statements about the text. Students will ultimately search the text for evidence that supports or refutes each statement. Statements can be objectively true or false, or they can be open to interpretation and designed to provoke discussion and debate. They can be customized to fit whichever skills, standards, or objectives you're working on—for example, identifying main ideas or analyzing characters and ideas. (See Figure 1.2 for details.)

3. Introduce the topic of the text and have students preview the statements before they begin reading. Encourage students to think about what they already know about the topic and to use the statements to make some predictions about the text.

4. Have students record evidence for and against each statement while (or after) they read.

5. Have students discuss their evidence in pairs or small groups. Encourage groups to reach consensus about which statements are supported and which are refuted by the text. If they are stuck, have them rewrite any problematic statements in a way that enables them to reach consensus.

6. Conduct a whole-class discussion in which students share and justify their positions. If necessary, help students clarify their thinking and call their attention to evidence that they might have missed or misinterpreted.

7. Use students' responses to evaluate their understanding of the reading and their ability to support a position with evidence.

Reading for Meaning Sample Lessons

Sample Lesson 1: Primary English Language Arts

Erin Rohmer introduces her 1st graders to the concept of evidence by posing this statement: "First grade is harder than kindergarten." After finding that all her students agree with the statement, Erin asks students why they agree: "What are you being asked to do this year in school that you didn't have to do last year? What new things are you learning that are more challenging than what you learned last year?"

As Erin collects students' ideas, she explains that the reasons and examples they are coming up with are evidence, or information that helps prove an idea. Erin goes on to explain that the class will be practicing the skill of collecting evidence from a story.

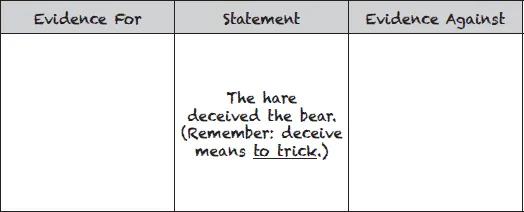

Today, the class is reading Janet Stevens's (1995) Tops & Bottoms, a story about a clever hare who tricks a lazy bear. For this initial use of Reading for Meaning, Erin asks students to consider just one statement: "The hare deceived the bear." Notice how Erin is helping students master an important and challenging vocabulary term—deceive—with this statement. After clarifying the meaning of the new vocabulary word with students, Erin reads the story aloud while students follow along. Students stop Erin whenever they find information in the story that seems to support or refute the statement. The class discusses each piece of evidence together and decides whether it helps prove or disprove the statement. Erin records students' ideas on an interactive whiteboard using the organizer shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Support/Refute Organizer for Tops & Bottoms

After finishing the story, Erin asks students to work in small groups to review the assembled evidence and then to nominate the three best pieces of evidence from the organizer. As the groups work together, Erin listens in to assess students' emerging ability to evaluate evidence.

Sample Lesson 2: Elementary Mathematics

Note: The following sample lesson has been adapted from Reading for Meaning: How to Build Students' Comprehension, Reasoning, and Problem-Solving Skills (Silver, Morris, & Klein, 2010).

Third grade teacher Heather Alvarez uses Reading for Meaning statements to help her students analyze and think their way through mathematical word problems before, during, and after the problem-solving process. First, she poses the problem: "Most 3rd graders get their hair cut four times a year. Human hair grows at a rate of about 0.5 inches a month. If you get 2 inches of hair cut off during a year, about how much longer will your hair be at the end of that year?"

Heather then asks students to decide whether they agree or disagree with these statements before they begin solving the problem:

1. The first sentence contains relevant information. (This statement is designed to build students' skills in separating relevant from irrelevant information.)

2. Human hair grows at a rate of 1 inch every two months. (This statement is designed to focus attention on the central information.)

3. To solve this problem, you need to find out how much hair grows in a year. (This statement is designed to help students expose hidden questions.)

4. You need to do only one operation to solve this problem. (This statement is designed to help students think through the steps in solving the problem.)

Students review the statements again after solving the problem to see how the problem-solving process challenged or confirmed their initial thinking.

Sample Lesson 3: Middle School Science

Directions: As we work through this lesson, I will be showing you some computer simulations on the whiteboard. You will be asked to collect evidence for and/or against each of these possible conclusions:

1. Most of the volume of an atom is empty space.

2. The electrons orbit the nucleus of an atom in much the same way that planets orbit the sun.

3. A carbon atom is more complex than a helium atom.

4. Most of the atomic mass of an atom comes from its electrons.

Planning Considerations

To develop a Reading for Meaning lesson, think about what you will need to do to introduce the lesson and to prepare for each phase of the lesson.

- Begin by asking yourself, "What standards do I intend to address?"

- After you select the reading for your lesson, ask yourself, "What article, document, or passage needs emphasis and intensive analysis? How will this reading help me address my chosen standards?"

- To analyze the reading, ask yourself, "What themes, main ideas, and details do my students need to discover?"

- To develop Reading for Meaning statements, ask yourself, "What thought-provoking statements can I present to my students before they begin reading to focus and engage their attention? How can I use different kinds of statements to help my students build crucial reading skills found in the Common Core?"

- To decide how to begin the lesson, ask yourself, "What kind of hook, or attention-grabbing question or activity, can I create to capture student interest and activate prior knowledge at the outset of the lesson?"

- To develop leading questions that provoke discussion, ask yourself, "What questions about the content or the process can I develop to engage my students in a discussion throughout the lesson and after the reading?"

Crafting Reading for Meaning Statements to Address Common Core State Standards

Figure 1.2 shows how you can design Reading for Meaning statements to address specific Anchor Standards for Reading.

Figure 1.2 Aligning Reading for Meaning Statements to Anchor Standards

Determine what a text says explicitly. (R.CCR.1)

- Everyone is unkind to Little Bear.

- Animals prepare for winter in different ways.

Make logical inferences from a text. (R.CCR.1)

- We can tell that Pooh and Piglet have been friends for a long time.

- Without taking Franklin's data, Watson and Crick wouldn't have succeeded.

Identify main ideas and themes. (R.CCR.2)

- The moral of the story is that teams can do more than individuals.

- Structure and function are intricately linked.

Analyze how and why individuals, events, and ideas develop, connect, and interact. (R.CCR.3)

- Pickles goes from being a bad cat to a good cat.

- After Maxim's revelation, the new Mrs. de Winter is a changed woman.

- The seeds of social change for women in America were planted during WWII.

Assess how point of view or purpose shapes the content and style of a text; distinguish between what is said and what is meant or true. (R.CCR.6)

- Chekhov wants us to judge Julia harshly.

- The writer's personal feelings influenced his description of this event.

Integrate and evaluate content that is presented visually and quantitatively as well as ...