- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

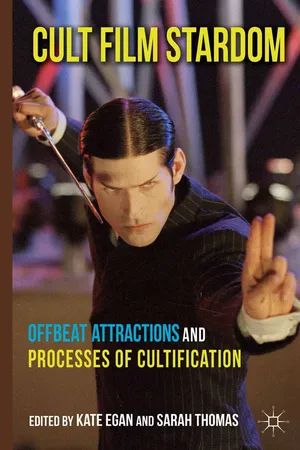

The term 'cult film star' has been employed in popular journalistic writing for the last 25 years, but what makes cult stars distinct from other film stars has rarely been addressed. This collection explores the processes through which film stars/actors become associated with the cult label, from Bill Murray to Ruth Gordon and Ingrid Pitt.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cult Film Stardom by K. Egan, S. Thomas, K. Egan,S. Thomas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Connecting ‘Cult’ and ‘Stardom’

1

Cult Movies With and Without Cult Stars: Differentiating Discourses of Stardom

Matt Hills

Work on cult media has often tended to explore the role of textual qualities (Eco 1995) and authorship (e.g. Hutchings 2003) in the cultification process. Stardom, however, has been significantly under-explored in relation to discourses of cult. Just as constructions of cult status can be multiple around a single text, for example taking in novelistic authors and filmic auteurs (Hills 2011), so too might stardom work in a variety of ways in relation to cult discourses.

In this chapter I want to consider the range of ways in which stardom has been linked to cultification. For instance, actors might be celebrated by knowledgeable, subcultural audiences but little known outside such circles, making them a type of ‘subcultural celebrity’ (Hills 2010). Alternatively, the extratextual lives and deaths of stars can also link them to posthumous cult status (Brottman 2000). And well-known performers might be read distinctively by fan audiences as powerfully linked to specific cult characters, becoming a sort of hybridized ‘charactor’ (Black 2004). Beyond ‘subcultural celebrity’, ‘death cults’ and cult ‘charactor’, however, stars can also be cultified by their repeated appearances in well-loved cult titles, e.g. Christopher Lee in Star Wars, The Lord of the Rings movies, Hammer horror, and The Wicker Man. But this raises the question of how cult discourse can be transferred from texts to stars, and vice versa. Under what circumstances of ‘affective contagion’ and intertextuality does ‘cult’ become attached to star personae? (Hills 2002). After first addressing the multiplicity of ‘cult stardom’, I will then move on to explore the possibility that a film text can be ‘cult’ without certain of its lead actors becoming ‘cult stars’. My aim is thus to consider the discursive limits to cult star/text articulations: where and why is ‘cult’ not discursively carried in relation to stardom?

‘Cult stardom’ is discursively multiple for specific reasons. Unlike articulations of cult status with textuality/authorship, ‘stardom’ carries historically sedimented, specific meanings of industrial fabrication, commodification and manufacture, making its links to ‘cult’ somewhat uneasy, if not contradictory. Whilst texts and auteurs can be understood by fans via aesthetic discourses, stardom has been far more strongly positioned as inherently industrial, forming part of the ‘industry of desire’ (Gledhill 1991) and a central tenet of the Hollywood studio system. By contrast, cult stardom attempts to integrate discourses of stardom with audience agency. That is to say, the processes associated with a star becoming cult are often strongly linked to subcultural audience discernment, recognition and valorization rather than marketing-led or industry/PR-related constructions of stardom. As such, the cult star can be understood to participate in a ‘decentring [of] the production of star discourses’ (McDonald 2000: 114). As Paul McDonald has usefully pointed out:

In the earliest years of the star system, producers and studios controlled the distribution of knowledge about stars. … With the Internet, the authorship of star discourse is opened out to many other sources. Unlike the institutional authorship of newspapers and television … the opportunity for an interactive construction of star discourse that was not possible with previous channels of mass communication [now becomes viable]. (McDonald 2000: 114–15)

For McDonald, the ‘dispersal of authorship in star discourse’ continues and promotes ‘the appeal of film stars’ (McDonald 2000: 115). And although McDonald’s focus is (somewhat reductively) on the Internet, I would say that cult stardom represents another form of stardom-as-structuration: it demonstrates how star discourses can be appropriated agentively by fan communities. This process, and its folding together of structure and agency, is considered in greater detail in what follows.

Subcultural celebrity, death cults and charactor: towards a structuration theory of cult stardom

Stardom is typically thought of as manufactured – as a product of industrial processes aimed at naturalizing concepts of ‘talent’ and ‘individuality’. As P. David Marshall notes, ‘the film star has operated as a symbol of the independent individual in modern society’ (1997: 82). Such approaches tend to theorize film stardom from a ‘top-down perspective’ (McDonald 2000: 117), contextualizing stars in relation to film production and ideologies of self. However, recent developments in the understanding of celebrity have begun to stress celebrity ‘from below’, or bottom-up processes of audience discourse and affect. For instance, Graeme Turner has noted a ‘paradox … in the discussion of the production of celebrity: that while whole industries devote themselves to producing celebrity, the public remains perfectly capable of expressing their own desires as if the production industry simply did not exist’ (2004: 91). One cultural symptom and outcome of this ‘paradox’ is perhaps the cult star, often embraced by fans of cult cinema via their own agency rather than as a consequence of marketing, publicity and industrial meaning-making: star cultification rather than cultivation, one might say.

However, the binary implied by McDonald and Turner is somewhat unhelpful, for it all too easily (and I would say falsely) polarizes stardom into ‘bad’ industry-led structures of domination, and ‘good’ agencies of audience-led empowerment. To read cult stars purely as ‘bottom-up’ movie stars, created by audience discourse, renders them just as ideologically suspect as old-school studio system stars: it is, once again, an ideology of the ‘independent individual’ that is reinforced here, albeit from the other side of the coin (the cult audience rather than the film industry). Thus, rather than celebrating cult stars only as ‘a dispersal of … star discourse’, I want to hold on to ‘top-down’ and ‘bottom-up’ perspectives, instead theorizing cult stardom as their highly visible, awkward and sometimes contradictory intersection and involution. To this end, a school of sociological thought which I have previously related to cult film (Hills 2008) is useful here: structuration theory. Variously expressed in the work of Anthony Giddens, Margaret Archer and Pierre Bourdieu (see Parker 2000), structuration theory aims to transcend divisions between structure and agency by considering structural properties of social systems as ‘both medium and outcome of the practices they recursively organize’ (Giddens quoted in Hills 2008: 447). Structuration analysis thus represents a theoretical attempt to fold together structure and agency rather than opposing them.

Bearing that in mind, a series of differentiated discourses of cult stardom can be analysed via structuration theory. Firstly, what I’ve termed ‘subcultural celebrity’ (Hills 2003a, 2010) is discernible as a mode of cult stardom. Here, rather than ubiquitous or widely known film stars being read distinctively by subcultural fan communities (Dyer 1986; Cohan 2001), cult fans can identify and celebrate ‘stars’ who remain little known or unrecognized outside cult circles. Nicanor Loreti’s (2010) book Cult People: Tales from Hollywood’s Exploitation A-list offers a good example of this process, featuring interviews with the likes of Lance Henriksen, Michael Ironside, Michael Rooker and William Sanderson. Using the notion of a Hollywood ‘A-list’ in his sub-title links Loreti’s work to concepts of celebrity, but this is the ‘Exploitation A-list’, i.e. it is very much subcultural rather than culturally ubiquitous. William Sanderson, it might be observed, is unlikely to carry the name recognition among audiences of an A-list Hollywood star industrially recognized as capable of opening movies, e.g. Tom Cruise or Matt Damon.

Loreti’s Cult People are described as demonstrating ‘commitment: no matter the project, Henriksen always delivers an amazing performance’ (2010: 35); while Michael Ironside is ‘a character actor whose mere presence is guaranteed to improve a movie’ (2010: 43); Michael Rooker has an ‘over-the-top charisma’ (2010: 107) and William Sanderson ‘is that rare thing: a character actor who’s managed to stay in control of their career’ (2010: 115). While Loreti displays an encyclopaedic knowledge of obscure exploitation films, he valorizes these subcultural celebrities, or cult stars, for their apparent distinctions: special commitment, excessive charisma and unexpected control. The repeated description ‘character actor’ indicates that outside exploitation’s ‘A-list’ these cult stars would not be deemed star performers, instead playing smaller movie roles where they are industrially positioned as subordinate to characters played. Loreti opposes this industry designation, however, using a range of evaluations to elevate cult stars. Rather than being viewed as in thrall to industrial structures, such figures are instead discursively repositioned as ‘rare’, and as significantly contributing to the films they appear in, thereby retaining and performing agency themselves. There is hence a discursive mirroring between cult fan and cult star (Sandvoss 2005): Loreti’s positing of agency and distinction reinforces his own cult fan agency as a discerning interpreter of trash/exploitation films. But within this mirroring, star/fan agency is set against, and in relation to, wider structures of industrial and cultural power. The ‘character actor’ is evidently not a Hollywood star – the term repeatedly being used as a marker of industrial subordination and difference by Loreti – just as ‘exploitation’s A-list’ is contained by its own subcultural parameters, very much acting as a qualified, bounded A-list in opposition to conventional Hollywood stardom.

Alongside the likes of William Sanderson and Michael Ironside, in Cult Cinema: An Introduction Ernest Mathijs and Jamie Sexton identify other cult actors who, as subcultural celebrities, have not been industrially positioned as Hollywood stars. They show how the mirroring of cult star/fan can go beyond discourses of agency and distinction, with some cult stars self-reflexively drawing on their own audience cultification:

Bruce Campbell, who has gained a particularly dedicated cult following without ever becoming a Hollywood staple, is an actor who certainly is well aware of his own cult status. This is evident through the ways in which he will sometimes obviously reprise his over-the-top, comic style within numerous cameo roles, but is most marked by the fact that he has played himself within a film based around him, entitled My Name Is Bruce … self-conscious performances often draw attention to the artificiality of acting. (Mathijs and Sexton 2011: 83–4)

Campbell has also penned an autobiography If Chins Could Kill: Confessions of a B Movie Actor, the blurb for which announces ‘you’ve probably never heard of him. But it’s a heck of a story nonetheless’ (2009: back cover). Campbell therefore acknowledges and plays with his status as a cult star while targeting cult fans as a niche market. The agency of cult fandom – ‘bottom-up’ generation and recognition of Campbell’s cult star persona – hence becomes a structure within which his agency as a writer-actor-director can subsequently function. Cult fandom can have its cultural distinctions mirrored and sold back to it by entrepreneurial cult stars and journalists. Loreti’s Cult People also participates in a neo-commodifying circuit of structuration, reinforcing the values of cult fandom by converting fans’ agency into a structuring of more or less canonically rendered cult stars. Again, fandom’s agency is sold back to it; a process of discursive mirroring which is also one of extracting profit. The ‘duality’ of structure and agency proposed by Giddens (Parker 2000: 9) is evident, as the agentive evaluations made by cult fans become coterminous with the structures within which the likes of Loreti and Campbell, in their turn, find their agency both constrained and enabled. In this view, cult stardom has a necessary duality; it is a product of fans’ agency-as-structure, and of stars’ ‘reflexive monitoring of action’ (Cohen 1989: 49) in order to attune themselves to, and co-produce, these cultural contexts.

Writing in Damaged Gods, Julie Burchill offers a contrast between different types of star:

Being a fan of an entertainer of genius can be an unrewarding business – you can withdraw your support at a moment’s notice and lack of it won’t make your target any less of a genius. But if you are a fan of a hackstar, you have power – you and others like you can stop listening/laughing/buying and the glorified nonentity will have nothing left, for when he ceases to please he ceases to exist. People appreciate this feeling of vicarious power. (Burchill 1986: 141–2)

It may be tempting to interpret the cult star – the subcultural celebrity – as a form of ‘hackstar’, since Burchill’s formulation shares an emphasis on audience agency. But her unhelpfully binaristic approach to structure/agency renders the ‘hackstar’ powerless and without any capacity to make a difference. For Burchill, the ‘hackstar’ is seemingly a mere puppet of, and conduit for, audience desires. However, the cult star is far from finding him or herself in this position; instead, cult stardom constrains and enables its subcultural celebrities, who are able to reflexively incorporate this status into their roles, products and performances. Whether it is Jean-Claude Van Damme in JCVD, or Bruce Campbell’s My Name Is Bruce, cult stars repeatedly engage with their own subcultural valorizations and personae. In Celebrity Culture and the American Dream, Karen Sternheimer argues that stardom can be read as reinforcing shifting ideologies of the ‘American Dream’ (2011: 18–23). While this may be true, to an extent, for mainstream or ubiquitous celebrity, I would suggest that subcultural celebrity typically refracts rather more modest economic concerns and ideologies: ‘I have to make a living. Sometimes I take films just for the moment, to make a living’, William Sanderson tells Nicanor Loreti (2010: 121). Cult stars tend to represent narratives of graft and entrepreneurial spirit – having to take the work that’s going, or making the most of a fan following – rather than exaggerated economic privilege and conspicuous consumption. Their careers can endure lengthy troughs as well as enjoying peaks in popularity, suggesting that rather than narrating social mobility (Sternheimer 2011: 4–5), cult stars might often represent financial struggles to ‘keep up’ or ‘go on’ with desired lifestyles. This position of relative economic weakness also bolsters the sense that cult stars, unlike stars more securely linked to Hollywood largesse, have a need to engage with their own subcultural valorizations and personae since this offers one possible route to self-commodification and entrepreneurial graft. The fact that cult stars may not enjoy hugely successful careers – having to ‘make a living’ as best they can – furthermore articulates them with Burchill’s concept of the ‘hackstar’, making especially visible the extent to which cult stars can literally trade on their fan followings. Structuration is significantly displayed and performed through this structure/agency dialectic; cult fan agency becomes a structural aspect within the cult star’s entrepreneurial self-performance.

Quite apart from issues of lifestyle, the manner of film stars’ deaths can also lead to or intensify their cultification. Unexpected and mysterious deaths, especially, can open up ongoing fan speculation around the circumstances of a star’s loss, as well as dramatically disrupting this celebrity’s industrially controlled image or persona (Hills 2002: 142). Mikita Brottman has analysed the ‘dead star’ phenomenon, arguing that movie stars’ deaths often lead to their final films being read cultically for signs, clues and portents of events that were to come. Brottman suggests:

Films like Rebel Without a Cause and The Misfits … help to establish cults of dead celebrities because they appear to expose … a trans cendental moment in cinema: that moment when a star is caught by the camera lens in a way that they themselves are unable to control. … In [such films] … a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction: Star-Making, Cult-Making and Forms of Authenticity

- Part I Connecting ‘Cult’ and ‘Stardom’

- Part II Cult Stardom and the Mainstream: Management, Mediation and Negotiation

- Part III Directors, Reputations and Cult Acting

- Part IV Cult Identities: Gender, Bodies and Otherness

- Part V Cult Stardom in Context: Connoisseurship and Film Criticism

- Index