eBook - ePub

Systemic Change Management

The Five Capabilities for Improving Enterprises

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Weaving together prescriptions with a series of cases, Systemic Change Management describes the value and how-to of a systemic or enterprise approach to organizational change. Each capability presented here promotes change, but when used together create synergies that magnify their individual impact within and between collaborating organizations.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

The Challenges in Excellence

CHAPTER 1

Systemic Change

What Is Systemic Change?

It was 5 a.m. on March 15, 1998, at the start of the first shift when Dan Ariens, son of the chairman and great-grandson of the founder of Ariens Company, walked through the main factory greeting employees.1 Ariens is a mid-size manufacturer of outdoor power equipment for consumer and professional use, producing snow removal and lawn care products while employing over 1,000 people. Dan was taking over as president, and everyone knew him. He had grown up and gone to high school with most of the workers, labored on the production floor during his college vacations, and held several positions in management. Five years earlier, he had moved to Indiana to run the Stens company, a division of Ariens and an international supplier of parts for outdoor power equipment. While he was gone, the company had been through a series of changes led by a new president who brought with him a team of senior managers that aggressively ramped up production and dealer bookings. Unfortunately, Dan Ariens’ homecoming was not the story of an heir returning to take over a profitable, privately owned business.

Family members had always led Ariens Company until Dan’s father, Michael Ariens, himself an excellent craftsman and manufacturing engineer, stepped aside as its president. Ariens was a vertically integrated company, established over a hundred years earlier as a metal foundry and subsequently extending its business into farm, garden, and snow removal equipment not just in its home state of Wisconsin but nationally. In 1992, after several years of losses, Michael had hired a president to be a turnaround manager and put the company on a firm financial footing. All had gone well. Sales hit new highs, and factories were running at full capacity. While the turnaround president met sales, production, and financial goals, how he did so bothered Dan. Bookings had grown, and production was at record levels, but there was too much inventory. Unit costs had improved, but quality was not where it should have been. Dan was concerned about the company’s finances; and many workers in the plant, while busy, were unhappy with how they were treated.

The troubles that had concerned Dan from a distance turned out to be much worse when he looked more closely. Per unit costs had dropped by the company’s producing at record levels and spreading out fixed, overhead expenses. The volume of finished goods filled the company’s factories, warehouses, and dealer pipelines, and Ariens Company was now choking on that inventory. Costs were too high to profitably sell products, like their snow blowers and lawn mowers, through large big box retail stores, and distributor fees ate much of what were slim profit margins. On top of it all, the turnaround president, whom Dan was now replacing, and his senior management team were owed large bonuses based on exceeding performance targets.

To this point, the Ariens Company story is a familiar one in American manufacturing. It was a medium-sized company that had a long and proud history, was an anchor in its local community, and played an important economic role in its region, employing over 800 people at four facilities. Located in America’s heartland, Ariens made products needed by farmers, gardeners, contractors, and homeowners, while providing jobs for local residents and work for its suppliers. Over the last two decades, the globalization of business and the need to compete with companies in low-labor cost and environmentally unregulated countries has required firms to operate in new ways. Ariens did the best that it could with what it knew, but that best was no longer sufficient. What remained were the ideals and values of its founders, and a need to find ways to improve, compete, learn, and change. The changes needed to be significant, and they needed to happen quickly.

No significant change is completed overnight, but the basis for an organization’s future operations is laid down by the way in which immediate actions are managed. Significant changes were required at Ariens to address multiple challenges. The series of changes Dan Ariens initiated took place within the company and involved reaching out to its suppliers, creditors, and partners. In his first month, Dan terminated three vice presidents and twelve directors, while forming a new management team. Failure to meet loan covenants required negotiations with bankers, and high costs and the low value of reaching Ariens’ dealers and customers through distributors required eliminating them. All the products in Ariens’ inventory had to be inspected and many required refurbishing. For the next year, nothing would be manufactured in several product lines because there was already so much inventory.

Inventory and how to avoid the same problems with it in the future became Dan’s overriding focus. He had to ensure that the company’s future would never be like the past, and that he would never again suffer from excess inventory. What he knew about “lean” as a production approach was promising because it required little to no inventory. The concepts—just-in-time inventory management, single-piece flow, value stream mapping, and process integration—helped Ariens improve its inventory problems and better its operations. The approach and associated methods were needed but were not sufficient. Broader changes were required to both focus inward and extend outward.

It was fortunate that Dan’s concern went beyond just profitability and included employees. Ariens was his family’s company, and he had grown up with many of its employees, not just working beside them on the assembly line but attending the same schools and playing on sports teams together. The company that bore his family name was a testament to his great-grandfather’s legacy in the early 1900s. Dan’s loyalty and reputation were important considerations as local bankers adjusted loan conditions that kept the company out of default on its credit line and loan covenants. Dan wanted to do more than merely fix the company’s current problems. He wanted to put in place a new foundation upon which a high-performing entity that lasted for decades would be built.

Within the next nine months, Dan had a new management team in place, and the company a new strategy. Ariens started investing in its workforce and did so with trainers hired through the Wisconsin Manufacturing Extension Program. By 2000, one hundred employees had been trained in lean methods. Ariens held its first kaizen event, but it did not succeed. The workforce was skeptical, and several employees began a unionizing effort. Not enough people understood why changes were needed. Dan treated this setback as a learning opportunity and took to the factory floor to promote continuous improvement techniques and demonstrate learning-by-doing.

Dan also sought help from a consulting firm. Its consultants were experienced managers who had led changes in their own companies and worked by teaching improvement methods to teams that determined what to do, where to do it, and then implemented the changes. Over the next three years, the combination of teaching new methods and making improvements empowered Ariens employees. For a week out of each month, Ariens formed employee teams that used those five days to select an area, identify new approaches, design improvements, and by Friday, or over the weekend, implement changes.

Examples of the changes included shifting production from assembly lines to autonomous work cells that were colocated, cross-functional units that completed an entire operation. Each of these cells made subassemblies that flowed into finished products. The cells required teams of workers who were cross-trained in all needed skills and involved in assessing and improving operations. The pattern was to periodically conduct events that improved their work cell’s quality and performance. Over time, as individual cells gained experience, they identified other cells with which they worked that were limiting their improvement efforts. Internal cells began working together and subsequently recognized that external suppliers, partners, dealers, and customers were potential sources for additional improvements. What people learned in their cells, and then in working across cells, was the basis for their working with other organizations.

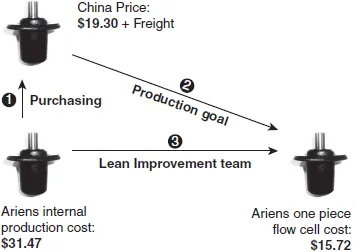

An example of an improvement, one that was both symbolically and operationally important, occurred when a purchasing department manager proposed buying an important part, a spindle bearing, from a supplier in China. The bearing was being produced internally using a specialized machine at a calculated cost of $31.47. A Chinese supplier offered the same part at a price of only $19.30. Before making the outsourcing decision, several leaders worked with the operators making the spindle bearing. They formed a team to carry out a rapid improvement event that redesigned, reorganized, and improved the production approach. The team’s redesigned spindle and production process reduced the cost to $15.72. Figure 1.1 illustrates the different production costs.

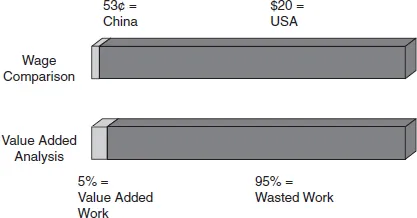

A similar challenge was addressed, with many other parts, subassemblies, and processes required to design, produce, ship, and service Ariens products. To compete with international manufacturers, Ariens had to make many, many small improvements like the redesigned spindle bearing. How could such efforts be substantial enough to overcome what most managers see as insurmountable labor cost disadvantages? As shown in Figure 1.2, there are significant differences in average hourly wages between Chinese ($.53) and American ($20) assembly workers. Where US companies can overcome the difference is by increasing the percentage of value-added work, calculated to be an abysmally low 5 percent.

Figure 1.1 Comparative Spindle Bearing Costs

The sum of improvements within and outside of Ariens went beyond production upgrades and technical issues. Dan modeled a fundamental new style of leadership and management thinking. Most organizations today choose the easy path by deciding to outsource production. Managers can quantify the savings in materiel, and then add in manpower, equipment, and facility savings from operating a smaller organization. In reality, a typical organization does not have managers with the leadership skill, involvement, and gumption needed to teach, engage, and support the changes to be made by an empowered workforce. That lack of leadership and an inability to promote change become detriments to long-term success. The company’s leaders and managers do not understand and never develop the skills to diffuse their efforts in working with their partners, suppliers, or customers.

Figure 1.2 Overcoming Differential Wage Disadvantages

What Ariens diffused was the leadership skill to understand, make, and sustain needed systemic changes. These abilities were developed by holding to some of its initial guiding principles. From the start of Ariens’ turnaround, every manager from every function was involved. Sales, marketing, customer service, engineering, product planning, purchasing, and finance and administration, led by the managers of those functions, learned new methods, formed teams, and developed and implemented changes. As they made improvements in their areas, they learned new techniques and lived through change processes. When subsequent improvement opportunities required changes across functions, the managers and their subordinates could draw upon similar language, methods, and a shared experience to leverage what was a common understanding that guided them in making sweeping gains.

The results from improvement and change efforts accelerated over time as new behaviors and ways of thinking prevailed over the whole system of cells, departments, and units of various organizations contributing to products and services. In 2004, after three years and over 400 kaizen events, Ariens Company began another wave of change. Production organization and its improvement efforts were restructured. Reporting relationships went from departments to product value streams. On the production floor, assembly lines were converted into manufacturing cells, and the operations between them were further streamlined. Internal changes diffused to external partners. Ariens shared what it learned and how it operated with its suppliers and dealers, teaching them their new approaches, helping them learn these methods to implement changes beneficial to their operations. Since managers from all functions, including finance, administration, engineering, customer service, and human resources planned, learned about, led, and participated in these efforts, they could show their improvements and teach these methods to their counterparts in other organizations. In 2005, as a result of many changes, Ariens profits had improved tenfold. Figure 1.3 shows the sequence of events within Ariens that spread to the network of organizations it depends upon.

Systemic Change

Ariens is like other companies that we profile in this book. The company made changes that took it from worse-than-average results to achieving and sustaining high performance. Their process involved not only changing themselves but extending improvements to other organizations. While it might seem ancillary to help other organizations, we found what we call a “systemic” approach to change as essential to achieving, and more importantly, sustaining high performance. Systemic change involves efforts by companies to change not only themselves but the system of which they are a part. For industrial companies, we refer to the system as the “enterprise,” or the network of firms supplying parts and services on which they depend in providing what their customers value. Syste...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Part I The Challenges in Excellence

- Part II The Five Capabilities for Systemic Change

- Part III The Way Forward

- Notes

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Systemic Change Management by G. Roth,A. DiBella in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Strategy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.