- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Tim Burton has had a massive impact on twentieth and twenty-first century culture through his films, art, and writings. This book examines how his aesthetics, influences, and themes reflect the shifting social expectations in American culture by tracing his Burton's move from a peripheral figure in the 1980s to the center of Hollywood filmmaking.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Works of Tim Burton by J. Weinstock in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Aesthetics

CHAPTER 1

Burton Black

Murray Pomerance

Back in his student days at the polytechnic, while helping a classmate’s younger sister—a sleepy, wan girl with a velvety gaze and a pair of black pigtails—to cram elementary geometry, he had never once brushed against her, but the very nearness of her woolen dress was enough to start making the lines on the paper quiver and dissolve.

(Nabokov, The Enchanter 5)

Perhaps no observation about his work could be more obvious than that Tim Burton has a biting fascination with black in particular and obscurity in general. In any of his films we can find darkness gravely positioned, in some more centrally than in others. To look at his drawings and water-colors, thickly stained with a substantial pen dipped in darkest ink, ink the color of Hades, is to be confronted, possibly lured, by a substantiality of line and contrast, a boldness of assertion, a stiff punctiliousness. The dense blackness of the lines confers confidence and suggests the unequivocal. One must rove willy-nilly around Burton’s world to encompass a substantial collection of his blacks, not only in fragmented passages in the films—Helena Bonham Carter in a raven black eye-patch and spider black shawl in Big Fish (2003), for example—but also in his predilection for including images—repeatedly and with burgeoning emphasis—of such heavily besmirched faces as Johnny Depp’s. There is a penchant not merely for makeup in general—Depp’s Mad Hatter takes this perhaps to its limits—and thus for the pretense of disguise that it offers, but for the pronunciation of the arch, impulsive, swiftly definitive black line, and a feeling for the richness of shadow. A striking—yet for me not quite magical—composition in Big Fish has Ed Bloom, Sr. (Albert Finney) fishing in a stream at dusk, a platinum wash of sunlight dropped across the placid mirror gray waters with long, pensive swaths of vegetation on both banks reaching off to the horizon and echoed in mysterious shadow on the water’s surface, a shadow that is what Nabokov called an “exact, beautiful, lethal reflection” (62). The figure itself is all silhouette, and doubled, since one fisherman stands up out of the stream while a second drops down into it, attached to him at the knee. The filmmaker has made his own public masquerade an iconic bolster to his visual forms: the dark eyeglasses, the entirely unruly explosion of black hair, the pools of darkness out of which his dark eyes seem to radiate, so that his very capacity to see, the volume of his gaze, trump the object of his vision. In the films, we find a kind of analogue: so striking in appearance are Burton’s visions, and so fully realized, that one has trouble seeing the forms they contain.

Black Line

Victoria Finlay discusses David Martin’s The Origin of Painting (1775) and reveals a delicious irony (for her, “challenge”) that it contains, in its depiction of a buxom maid sitting on the lap of her boyfriend and using, notably, charcoal to imprint, on the wall behind her, his profile as revealed by a shadow cast from candlelight. For Finlay, the painter is “using something that is already burned out to symbolize a love you want to last forever” (79). The relationship between destruction by fire and the revivification made possible in art and printed literature was generic, since the pigment base of the color black was always generated by burning organic substances, sometimes vine wood or ivory but more typically select vegetative materials, such as the “oak apple” that, mordanted with iron salts, made a strong dye in the middle ages, by which time “black had become the style in princely clothing” (Pastoureau 92). When dyeing in black became popular (by the fourteenth century, and restricted to only certain artisans), its affinity with Satan and those who owed him allegiance had dissolved to some degree in Western culture, as had a notion from thirteenth-century chivalric romances that black was principally the “color of the secret” (74). Now, it was being openly worn as a sign of purity and modesty, diligence and gravity, and by the middle of the fifteenth century was finding its way before the public consciousness in the form of printer’s ink. “Ink became the black product par excellence,” writes Pastoureau: “It was a heavy, thick, very dark ink that a mechanical press made penetrate the fibers of the paper and that perfectly resisted the various vicissitudes to which books were subject” (115). Matched exquisitely with the exceeding blackness of ink was the exceeding whiteness of paper: “A chemical reaction took place between the ink and the paper that made any erasure impossible” (117), and thus ink was not only the embodiment of the spirit of rebirth but also a signal of permanence, correctness, impeccability, and absoluteness. If the world was provisional, the book would endure it, thanks to the ultimate and penetrating blackness, the ineffable blackness, of the ink with which it was pressed.

With Burton, black is a rebuke to timidity, even a denial explicit and acute of the hesitant, deliberative, calculating impetus. The line is made by a bold and unequivocal stroke, inked with purpose and certainty. But just as with the blackness of book ink upon the bleachy paper, the dark form not only stands out optically from its ground but, as we gaze at and decode it, disintegrates the ground altogether; it is the black line that survives our gaze, that becomes the be-all and end-all of the act of looking. If the blackness of the line is dense enough it gains the power to disavow the ground it cleaves, much as a belabored morbidity can blot out the vivid brightness of life. If we look at Corpse Bride (2005), we find a strident thrust toward the world of the au-delà (a chthonic and black world, not a superior mount seducing ascension but a destination to which the characters have dropped: life as gallows). The blackness here, as in Beetlejuice (1988), is sourced in a Romanticism attached to harvest festivals: the blackness of the Hallowe’en cat or witch, of the cloud-sheathed night (through the shades of which the moon peeks impotently, as in Sleepy Hollow [1999]), of the spider creeping upon the snowy gravestone (Ed Wood [1994]) and achieving its dominating form through a distinct linearity. This linear blackness is also (one feels shame in pointing this out) the extrusion of the scrawl, the unsuspended assertion of inwardness by way of the marketplace of language. So in a way every black figuration—a contorting dance of the nib or brush—is also a sentence. How deified is the blank page until one begins to mark it. Blackness is the first, the most endearing, macula. It needs to be cleansed by our looking, our interpretation, our importation of order.

In a discussion of the sublimity of Gothic architecture, E. H. Gombrich points specifically to Goethe’s evaluation of the Strasbourg Minster in Of German Architecture. (This is a high, profusely ornamented stone structure with a clock almost as big as a small cathedral—a perfectly Burtonian mechanism, with little figures prancing naughtily and in suggestive jerks—perched on one of its interior walls.) Goethe preaches that misunderstanding should not allow the “soft doctrine of modish beautymongering to spoil your taste for the significantly rough” (Goethe 116, qtd. in Gombrich 75). Goethe then proceeds to declaim the virtue of manly Albrecht Dürer by comparison with the “theatrical postures” and “feigned complexions” of “effeminate” artists who “have caught the eyes of the womenfolk” (76). This contradistinction between the bulky, even brooding angularity and sturdiness of manliness and the overdecorated falsity of effeminacy, which Gombrich highlights, was to be found as well, claims he, in the writing of Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768), for whom “beauty is a comparatively late fruit of artistic development, preceded by the grand and the lofty.” But can we not find this same (gendered) tension in the way Burton contraposes stiff or remarkably sinuous black lines, offshoots of one another, stressors and supports, with haphazardly colored, overdecorated, overelaborated grounds?

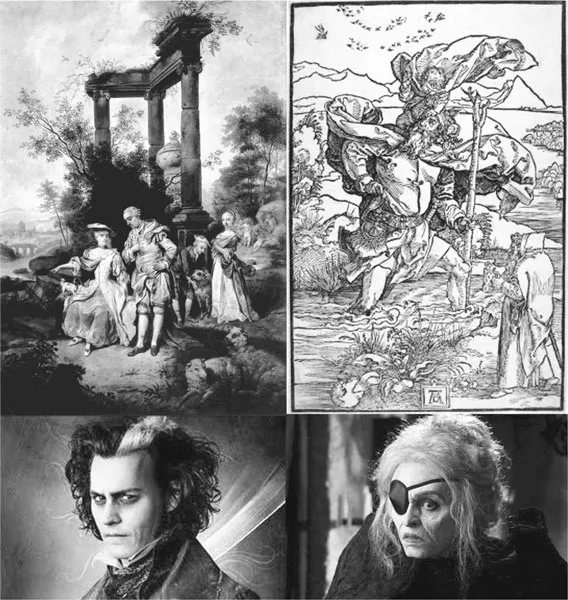

In Alice in Wonderland (2010), for example, the elaborate colorations (Wonderland’s blossoms) and striking delineations (Wonderland’s curlicue iron gates) spring only from the creative impulse and mastering plan of the artist, who limns and arranges it all: as a botanical space, Wonderland is female; as a product of engineering, it is male. The White Queen (Anne Hathaway), for example, is an important black blot, because of her dark mouth and darkened eyes and the white gown that accentuates them; as she cavorts in her black-and-white palace surrounded by the shockingly multicolored beings and forms of the wonderland, she represents a kind of neomodern claim for revivified masculinity, poise, strength, and purpose. Gombrich seals his presentation with a pairing of Johann Seekatz’s Goethe Family Portrait of 1762 (in which the poet as a youth was posed as a pretty shepherd) and Dürer’s 1501 woodcut Saint Christopher. Can we not see the gap between these two images, if we imagine the exciting colorations of the Seekatz—its lemony cloud and soft green lawns—and recognize in the Dürer the forceful action of the cutter’s hand with his blade, a hint of what Burton would seek to achieve in his films when he counterposes against a lavishly decorative field some eccentric figure, always staunchly moralistic and as dark as death?

Hathaway’s morbid White Queenly mouth and sharply drawn, horizontally lined White Queenly eyes dominate the frame, even though as she is composed with Alice she stands smaller than the principal figure and in the background. This is partly due to the brightness of her dress and partly due to a slight excess of illumination on her figure, as well as to the makeup (by some of the dozens of artists who worked on the picture). In Sleepy Hollow, we frequently see washed-out horizons with pallid coloration, and softly colored foreground fields, punctuated by arbitrarily rising black (or very dark) verticals: gnarled leafless trees, fence posts, or even the somber figure of Depp clad in black. Edward Scissorhands (1990) is a fantasy in pastels contraposed against turgid and grinding blacks and grays. In one shot we have a dreamy sky (shot through a high-contrast filter to accentuate the clouds), Kathy Baker with her copper red hair and magenta dress, and then the stark chiaroscuro figure of Edward (busily cutting her hair), with his jet black tonsoriality sprouting off in myriad directions like a fungus from a dark forest. In Sweeney Todd (2007), Depp’s persona is an angular composite of slashing black lines, the tarry hair accentuated in its darkness by a white streak, the eyebrows darkened and lengthened (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Top left, Johann Conrad Seekatz (1719–1768), Goethe Family Portrait (1762). Top right, Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), Saint Christopher with the Birds (c. 1501). Bottom left, Johnny Depp in Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street, digital frame enlargement. Bottom right, Helena Bonham Carter in Big Fish, digital frame enlargement

As to that now somewhat celebrated figure Edward Scissorhands, so named because out of black crevices at the ends of his arms his inventor has perched not hands but shears, this character is altogether a humanoid blot of blackness—a “blot” in the sense invoked by Slavoj Žižek, who points to a phallic spot by means of which “the observed picture is subjectivized: this paradoxical point undermines our position as ‘neutral,’ ‘objective’ observer, pinning us to the observed object itself. This is the point at which the observer is already included, inscribed in the observed scene—in a way, it is the point from which the picture itself looks back at us” (91). (Burton’s blacknesses, similarly, are his pictures speaking of themselves to their viewers, his self-consciousness in manifestation.) Scissorhands is conceived in an obscure relation between science and art under the hands of a magus/engineer, “born” in a shadowy and superior majestic darkness that is materialized through decrepitude, overwhelming machinery, a generally slow vortical movement of the danse macabre. As he moves among the hypnotized bourgeoisie of a spotless and febrile (Floridian) housing tract, Edward, the point of a stylus, etches a line that circles, recapitulates, arches forward. The space he circulates in is, at the same time, a substrate he dominates optically by flying upon it, a surface arranged by Burton as a tranquil, and tranquilized, village of harmonious and infantile color, a candy world: the factory interior in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (2005) will reprise it with greater density and greater saturation. All our fears and regulations, our repressions and cultural formations, are there for him to tread upon with his black feral dignity.

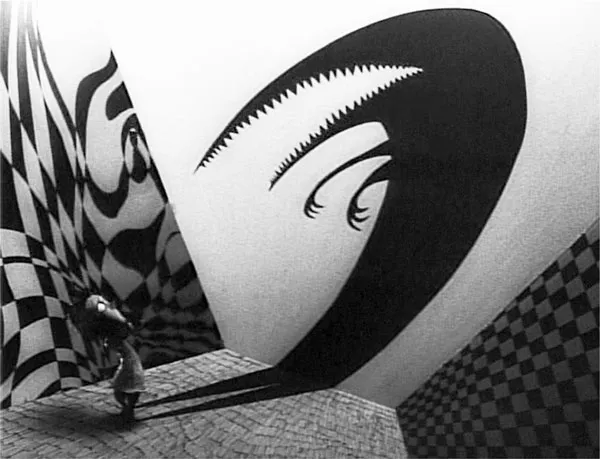

Is Edward (not) derived from Stainboy, a weevil-headed Web-based animated character Burton presented in 2000? In one drawing, we see Stainboy diminished by a threatening environment, massive trees on either side (as in the forest of The Wizard of Oz [Victor Fleming, 1939]), a looming structure behind him, and the little inky creature with the huge eyes (observing or retreating?) upon a black-and-white check floor. In The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), where many of the characters are made of black stick-limbs, we see the “self” as an emaciated and ghostly form, outside the fleshy world, not really there. In an early Burton drawing that became part of Burton’s Vincent (1982), we see the shadow of a dragon-self stretching out from a small and fragile figure in a huge closed room—stretching out toward a wall, then up the wall, curving and rearing into an angry beast with its toothy maw open in rage. Rage, or impotence. A conventional cartoon of a fellow so timid he’s afraid of his own shadow? Or is the shadow perhaps afeard of the hairy little man emitting it? Either way, the graphic point is the puissant blackness of the figuration that dominates the frame (Figure 1.2).

In calling to mind Burton’s history as a graphic artist who came under the influence of film early in life—growing up in Burbank, he was “fascinated with pop culture, taking inspiration from animation and cartoons, television, children’s literature, Hammer horror films, Japanese monster movies and B-grade science fiction films” (Hanover Gallery exhibition catalogue)—we may arrange his oeuvre, its use of the signal dark demarcation against a structured and diminished color field, for comparison with those of other notable filmmakers who began their careers with art and/or design. Here, too, arbitrary as this comparison is, we find eccentricity and a kind of timid obscenity in Burton—obscenity in the precise meaning of the word, “out of the scene.” He is distinct, characteristic, self-styled, but also outside a filmic tradition in a way and thus, perhaps, merely immature. “Outside a filmic tradition”: he summons generic styles and ideas, but he does not work in accord with a historical community of other workers, in his artistic impulse deriving more, perhaps, from the fairly recent (and subservient) line of engravers (admitted to the Royal Academy only as late as 1853 because they could make records of what painters had done [Hopkinson 9]).

Figure 1.2 Vincent from Vincent, digital frame enlargement

In Jean Renoir, to name a filmmaker who migrated from painting to cinema, light is used always to draw us to central objects or acts of importance in a scene, and darkness is a way of framing light, not intruding upon it. Eugène Lourié often composes scenes (in black and white) with a minimal use of highlight and a full range of variously lit blacks and grays, as in Colossus of New York (1958)—but the rationale of the story invokes principles (radiation, mutation) that account for the generally dark mood: this darkness is not imposed on an otherwise fully articulated field. William Cameron Menzies builds his shots with architectonic forms and uses darkness expressively—even expressivistically—but not as a principal method for pointing, as Burton does. Federico Fellini working in black and white is a man obsessed with brilliance and the radiant halo of illumination, and darkness merely gives linear accentuation to his forms (the raven nuns in 8½[1963]). In color he plunges us into a dream where blackness as such is virtually absent (for a good example, see the scene in Amarcord [1973] in which the ocean liner Rex passes by the little village at night). Nathan Juran blackens as a way of identifying locales, objects, and fragments, and these forms become dark onscreen as a natural extension of their presence to sight: in The Deadly Mantis (1957), for example, a dark circular radar screen with a sharp white rotating line inside it, all this housed in a clearly visible metallic cabinet. Nicholas Ray plays with the dynamic interaction of colors more than with line and figuration (Cyd Charisse yawning on a couch in Party Girl [1957] or James Dean sprawling on one in Rebel Without a Cause [1955]), in this being a kind of modernist in the tradition of Kandinsky and Malevich. And Alfred Hitchcock’s color films position tonal objects and forms to emit a kind of memorial radiation (Kim Novak in Podesta Baldocchi in Verti...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Mainstream Outsider: Burton Adapts Burton

- Part I: Aesthetics

- Part II: Influences and Contexts

- Part III: Thematics

- Contributors

- Index