![]()

Chapter 1

Placing Architecture

In architectural terms, ‘context’ generally refers to the place in which architecture or buildings are located. Context is specific and significantly affects how an architectural idea is generated. Many architects use context to provide a clear connection with their architectural concept, so the resultant building is integrated and almost becomes indistinguishable from the surrounding environment. Other responses may react against the environment, and the resultant buildings will be distinct and separate from their surroundings. Either way, the critical issue is that the context has been studied, analysed and responded to deliberately and clearly.

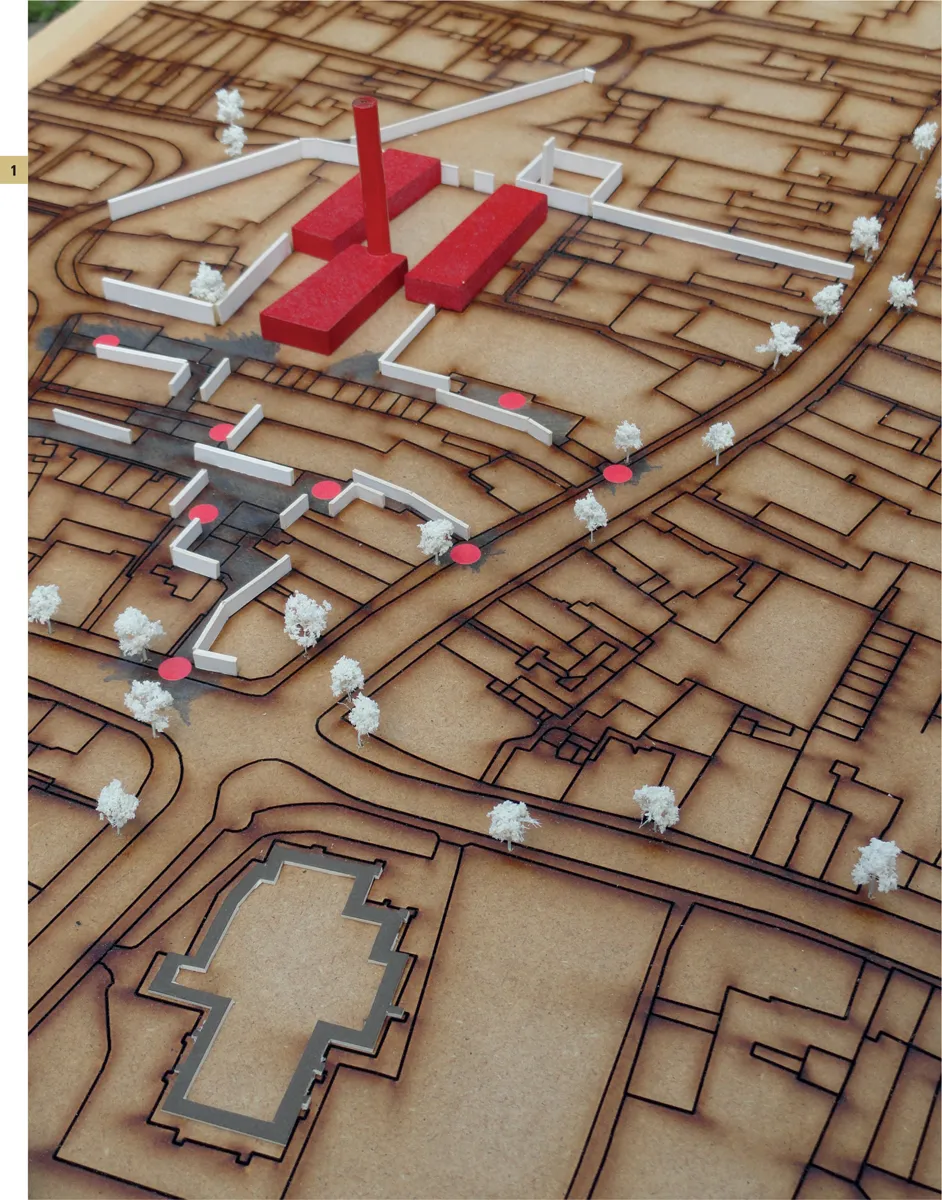

1. Townscape model

This model of a laser-cut map highlights aspects of a townscape: a project site is identified as a series of red blocks to distinguish it from the surrounding city site.

Site

Architecture belongs somewhere, it will rest on a particular place: a site. The site will have distinguishing characteristics in terms of topography, location and historical definitions.

An urban site will have a physical history that will inform the architectural concept. There will be memories and traces of other buildings on the site, and surrounding buildings that have their own important characteristics; from use of materials, or their form and height, to the type of details and physical characteristics that the user will engage with. A landscape site may have a less obvious history. However, its physical qualities, its topography, geology and plant life for example, will serve as indicators for architectural design.

There is a fundamental need for an architect to understand the site that a building sits on. The site will suggest a series of parameters that will affect the architectural design. For example, broad considerations might include orientation (how the sun moves around the site) and access (how do you arrive at the site? What is the journey from and to the building?).

The location of a building relates not only to its site, but also to the area around it. This presents a further range of issues to be considered, such as the scale of surrounding buildings and the materials of the area that have been previously used to construct buildings.

On site it is important to imagine ideas of form, mass, materials, entrance and view. The site is both a limitation to design and a provider of incredible opportunities. It is what makes the architecture specific and unique as no two sites are exactly the same. Every site has its own life cycle, which creates yet more variables in terms of its interpretation and understanding. Site analysis is critical for architecture, as it provides criteria for the architect to work with.

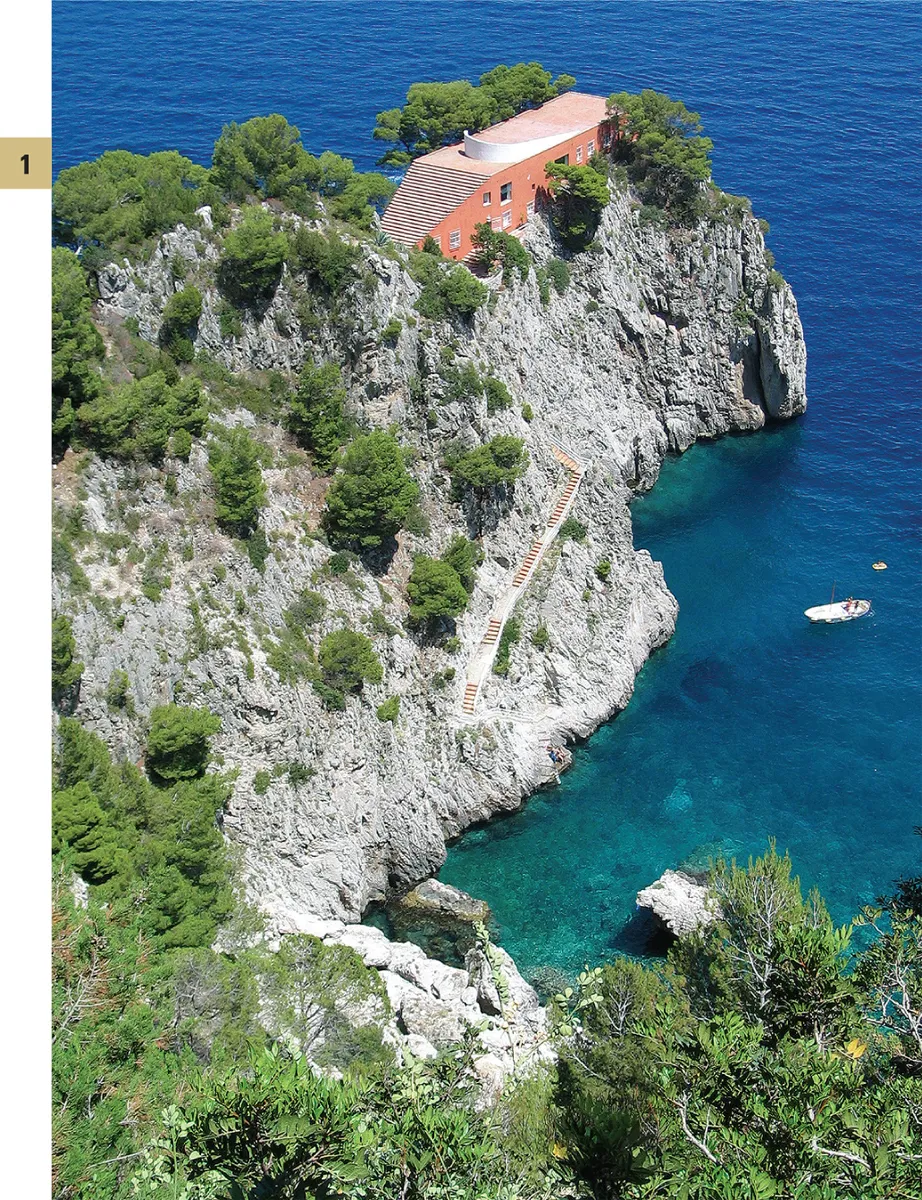

1. Casa Malaparte (Villa Malaparte), Capri, Italy Adalberto Libera, 1937–1943

Adalberto Libera provides us with a clear example of a building responding to its landscape. The Casa Malaparte sits on top of a rocky outcrop on the eastern side of the Island of Capri in Italy. It is constructed from masonry, and is so intrinsically connected to its site that it actually appears to be part of the landscape.

2. A city skyline, London, UK

In an urban environment, a mixture of historical and contemporary buildings can work well together. The London skyline, viewed here from the South Bank, shows a city that has evolved over hundreds of years, each element connecting to the other in terms of material, form and scale.

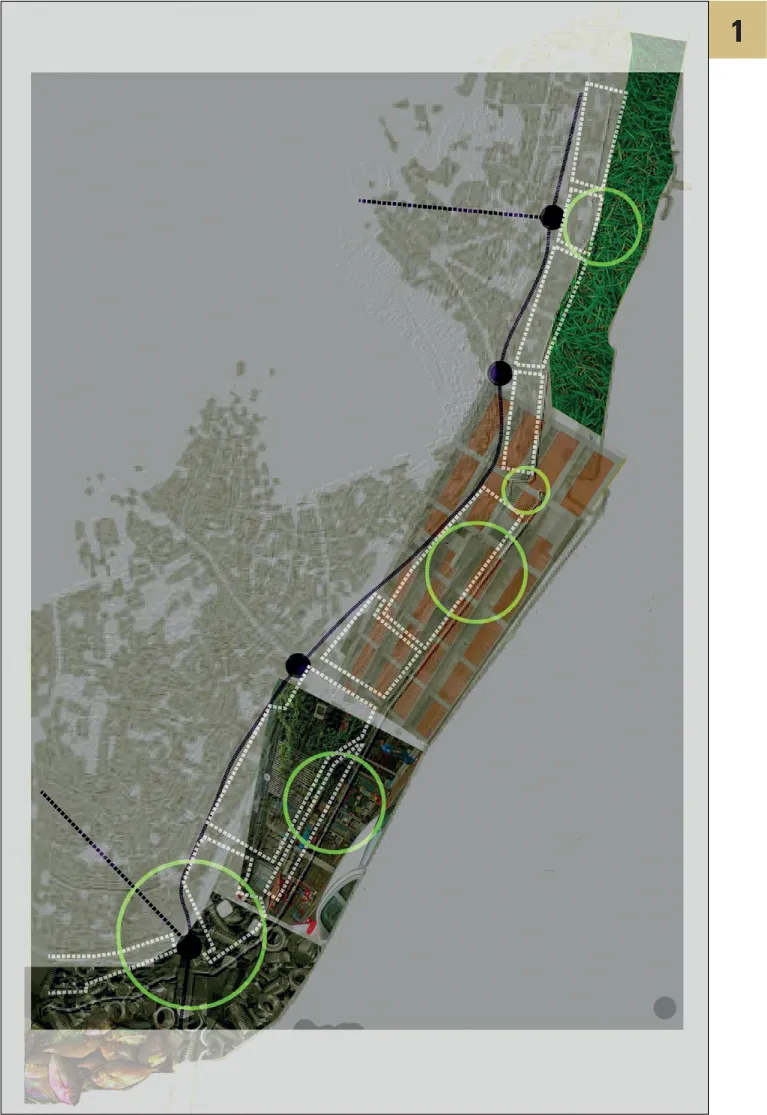

1. Istanbul: Karaköy analysis

This is a map of an area of Istanbul, alongside the water edge, the study identifies the key centres of activity along the map and also describes the various intended ‘character areas‘ through use of colour.

SITE ANALYSIS AND MAPPING

Techniques to record and understand a site are varied, from physical surveys (measuring quantitatively what is there) to qualitatively interpreting aspects of light, sound and experience. Most simply, just visiting a site to watch and record its life cycle can provide clues about how to produce a suitable design response.

Contextual site responses respect the known parameters of the site. Acontextual responses deliberately work against the same parameters to create contrast and reaction. For either approach it is necessary for the architect to have read the site, and properly understood it via various forms of site analysis.

To properly analyse a site it must be mapped, which means recording the many forms of information that exist on it. The mapping needs to include physical aspects of the site, but also more qualitative aspects of the experience and personal interpretations of the place.

There are a range of tools that can be used to map a site, investigate it and produce a design from its indicators. These are analytical tools that allow the site to be measured in a range of different ways.

2. Personal interpretations of a site

A collage image of London comprises a set of sketches of a journey, overlaid on a train map; a personal interpretation of a visit to London.

TOOL ONE: PERSONAL INTERPRETATION OF A SITE

The first impression we have of a place is critical. Our personal interpretations of the overall character of a site will inform subsequent design decisions, and it is important to record these honestly and immediately.

The idea of a personal journey around a site and the interpretation of it is something that Gordon Cullen focuses upon when he describes the concept of ‘serial vision’ in his book The Concise Townscape (1961). This concept suggests that the area under study is...