![]()

Chapter 1

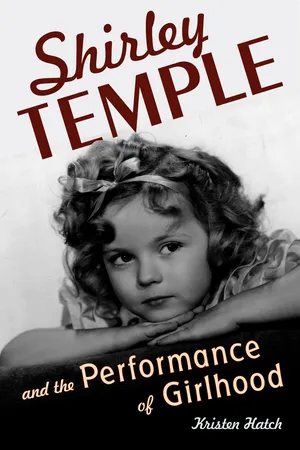

America’s Sweethearts

Mary Pickford, Shirley Temple, and the “Decline of Sentiment”

Before Shirley Temple became a star in 1934, the most popular icon of American girlhood was not a girl at all but an adult woman, Mary Pickford. Pickford was one of the first stars to emerge out of the fledgling film industry, having made her screen debut in 1909 at the age of seventeen. Throughout the teens and 1920s, Pickford was consistently identified as the most popular performer in the world, her name synonymous with movie stardom. She did not play children exclusively; indeed she enacted adult roles in the majority of her films. However, following the First World War, she began playing children with increased regularity, and publicity photographs often showed her in the guise of young girls. Indeed, her screen persona was so strongly associated with youth that she was imagined to be the very personification of childhood: “The spirit of spring imprisoned in a woman’s body; the first child in the world.”1 Although her popularity had waned considerably by the end of the 1920s, as late as 1933 Pickford was in discussions with Walt Disney to play Alice in Alice in Wonderland.2

Shirley Temple’s ascendance to stardom in 1934 prompted journalists to recall Pickford’s heyday, and Twentieth Century-Fox nurtured such comparisons by starring Temple in remakes of several of Pickford’s most popular films: Daddy Long Legs (released as Curly Top), Poor Little Rich Girl, Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, and A Little Princess.3 More than Temple’s reprisal of roles associated with Pickford, however, Pickford and Temple were linked by virtue of their tremendous popularity. Several journalists noted that Temple had displaced Pickford as “America’s Sweetheart,” claiming that “Shirley’s only feminine rival as a box-office draw in the whole history of films is Mary Pickford.”4 And both were icons of girlhood whose images reached far beyond the movie theater, entering into the popular vernacular. Thus, girlhood held a prominent place in the iconography of Hollywood during the industry’s formative years. Scholars have often attributed the prominence of girlish stars in the silent era to the pleasures associated with what Gaylyn Studlar terms a “pedophilic gaze.”5 However, when we consider Temple’s career as an outgrowth of Pickford’s, it becomes clear that their performances of girlhood played an important role in negotiating the twentieth century’s first culture war by evoking what might be better termed a “juvenated” gaze.

In his seminal study of film stardom, Richard Dyer argues that the elusive quality that helps to transform performers into stars—the quality of “charisma”—arises out of the star’s ability to embody ideological tensions. Marilyn Monroe, for example, “has to be situated in the flux of ideas about morality and sexuality that characterized ’50s America. . . . [Her] combination of sexuality and innocence is part of that flux, but one can also see her ‘charisma’ as being the apparent condensation of all that within her. Thus, she seemed to ‘be’ the very tensions that ran through the ideological life of fifties America.”6 Pickford, Temple, and other performers of girlhood likewise embodied a cluster of tensions within American society, tensions that might best be understood in relation to what Lea Jacobs describes as the “decline of sentiment” in American culture, the overturning of a traditional aesthetic of Truth and Beauty in favor of fun and and what was popularly termed “realism.”

Mary Pickford’s screen career reached its apex in the wake of World War I, when the United States began to assume its central position in the world’s industrial economy and the conditions of a distinctly American modernity began to develop. As the economy boomed, Americans incorporated emerging technologies—automobiles, streetcars, movies—into their lives, and the texture of everyday life underwent profound change. At the same time, the United States was shifting from a largely rural nation to a predominantly urban one. Following the war, workers flocked to American cities—New York, Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles—to labor in these new centers of machine-age production. Black sharecroppers migrated from the South, white farm workers moved from small towns and rural areas, and immigrants relocated from Asia and southern and eastern Europe to these metropolitan centers. By 1920, for the first time in its history, the majority of Americans lived in cities.7 Inhabitants of these urban environments found themselves surrounded by people whom they didn’t consider to be of their own kind, while they remembered an idealized past of homogeneous, small-town life that was intelligible and orderly, in memory at least. Further, workers experienced a diminution in their autonomy as labor in the new, industrial economy was governed by the time-clock, the boss, and the machine. At the same time, the social controls governing private life were relatively scarce given the potential for anonymity within the city.

This shift from an agrarian to an industrial economy, from a nation of small towns to one of large cities, gave rise to a host of other changes, not least of which was the proliferation of commercial amusements—including the cinema—that catered to a mass audience of wage earners. In the 1920s, the center of American cultural production had relocated from Protestant New England to polyglot New York. Whereas the WASP stronghold of New England had once been the nation’s literary center, the publishing industry was now located in the borough of Manhattan, which was also the site of Tin Pan Alley, Broadway, and the Harlem Renaissance, all of which helped to bring black and Jewish artists and musicians to the center of American cultural production. As a consequence, the WASP tastes and values that had defined nineteenth-century culture began to be derided as old-fashioned in some quarters. Hollywood, overseen by Jewish movie moguls, peopled by immigrant actors and directors, and transforming working-class men and women into influential stars, was perceived as a threat to middle-class, Protestant hegemony.

During a period in which the United States became the exemplar of modernity, Pickford and Temple embodied the tensions that accompanied the nation’s rapid urbanization and helped Hollywood to navigate this culture war. Both Pickford and Temple were strongly associated with their blonde hair, Pickford’s falling down her back in a voluptuous cascade of curls, Temple’s carefully corralled into precisely fifty-six ringlets. Their curls helped to link them to a tradition of sentimental literature that featured innocent, blonde girls modeled after Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Little Eva from Uncle Tom’s Cabin. And their curls signaled their status as innocent, an innocence bound to their whiteness and youth. In many ways, it was precisely this image of innocence that seemed most under threat in the early twentieth century: white hegemony threatened by migration and immigration, and children potentially corrupted by the burgeoning mass culture. Pickford’s and Temple’s indelible innocence worked to proclaim the stability of these categories in a modern setting, thereby appearing to reconcile the tensions between Victorian and modern aesthetics and values, suggesting that the treasured elements of America’s past need not be lost to modern life.

Sweetness and Light

In a letter written to Alice Stuart-Wortley in 1917, the British composer Edward Elgar captured the feelings of loss and nostalgia provoked by industrialization and the mechanized killing of World War I: “Everything good & nice & clean & fresh & sweet is far away—never to return.”8 His was a sentiment shared by many who understood the changes that attended rapid industrialization in terms of loss rather than progress. American film, which developed in tandem with this destruction, was experienced as both a catalyst and an antidote to this sense of loss. It was a catalyst insofar as it was representative of modernity: a nineteenth-century invention turned commercial amusement for the entertainment of audiences who labored in the industrial economy. And it was an antidote to the extent that it offered a respite from the hurly burly of modern life.

Elgar’s mourning the loss of what was “good & nice & clean & fresh & sweet” might be understood to refer not only to the imagined simplicity of pre-industrial life but also to a public sphere that was characterized by decorum and restraint. Mary Pickford and Shirley Temple both offered the promise of reconciling old values with emerging mores, of recapturing these lost qualities and transplanting them to modern entertainments. However, more than simply appealing to conservative tastes, these stars worked, in Richard Dyer’s formulation of stardom, to embody the tensions between old-fashioned values and a new, modern aesthetic.

Girlhood had been a staple of sentimental melodrama throughout the nineteenth century, associated with virtue and pathos in the multitude of stage plays that featured children: Bootle’s Baby, Editha’s Burglar, and especially Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which was performed continuously from 1852 until the 1930s. However, American culture at the turn of the twentieth century had begun to reject sentimentality in favor of laughter and what Ann Douglas terms “terrible honesty,” which was popularly termed “realism.” This shift in taste is reflected in attitudes toward Little Eva, one of the central characters in the countless stage adaptations of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Previously, Little Eva had been one of the most beloved characters in American culture. In the late 1870s and early 1880s, the death of little Eva was regarded as the high point of the Tom show. When one production eliminated Eva’s deathbed scene in 1878, reviewers found the change “inexcusable.”9 And when the scene was interrupted by a heckler during a Boston production in 1880, “he was promptly and almost fiercely hissed into silence.”10

However, at the turn of the century the angelic child had begun to be reviled as a manifestation of old-fashioned, sentimental culture. Eva came to be regarded as “a sickly, puling little prig,”11 and her scenes with Uncle Tom “the most transcendent piece of claptrap known to the stage.”12 Rather than eliciting tears, Eva’s preoccupation with her own death now seemed absurd: “[Eva] has become ridiculous. A child whose only subject of conversation is speculative interest in heaven and whose only yearning is to die is not now an engaging creature.”13

This rejection of Little Eva is one manifestation of a much broader shift in American taste culture, one that saw the overturning of the ideals of Truth and Beauty that had once shaped American literature. Andreas Huyssen attributes this shift, in part, to a rejection of mass culture. He traces the development of an association of the popular arts (particularly novels) with women to the late nineteenth century, arguing that Modernism developed as a reaction formation against the perceived femininity of mass culture.14 According to Huyssen, the rejection of idealism that began to take hold in European art and literature in the nineteenth century was also a rejection of a mass culture that had come to be defined as feminine. Similarly, Ann Douglas identifies a “matricidal” impulse in both high art and popular culture during the 1920s, an impulse that was often expressed in terms of a rejection of the “feminizing” effects of sentimental culture. Under the influence of Freud, Marx, and Nietzsche, artists and writers favored brutal truths over uplift and decorum. Innocent young girls had been a staple of nineteenth-century sentimental art and literature, and they were anathema to modernism.15

Hollywood was not untouched by the sea change in popular and high-art aesthetics. Lea Jacobs demonstrates that, during the 1920s, Hollywood filmmakers and film reviewers, too, rejected sentiment in favor of naturalist aesthetics. Tracing what she describes as the “history of the decline of sentiment,” Jacobs demonstrates that during the 1920s trade reviewers evaluated films in accordance with an aesthetic that rejected the sentimentalism that had dominated American tastes just a decade earlier.

Hollywood’s celebration of girlhood would therefore seem to be at odds with the general trend in American mass culture. Even before Pickford adapted such classic novels as Daddy Long Legs, Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, or Pollyanna to the screen in the late teens, these stories were considered old-fashioned. They came in for as much invective as they did praise, maligned as saccharine and overly sentimental. Writing of Ruth Chatterton’s performance as Judy in the Broadway production of Daddy Long Legs, one reviewer described the play as “sentimentalism sentimentally interpreted, [a] turnip smothered in sugar, offered as an apple of life.” Audiences’ craving for the empty calories of sugary sentiment is attributed to the drab monotony of modern life: “living lives emotionally impoverished, performing dull chores or engaged in routine jobs, they sink back in blissfulness at this version of a dream come true. . . . [I]n monotonous lives there is a great craving for sweetness, and so, since the disguise is plausible, the general public is glad to be cheated to indulge in this perversion of life.”16 The review captures the emerging terms by which popular performances were understood. No longer associated with uplift, sentiment was now viewed with suspicion, understood to be a means of manipulation rather than inspiration, a drug to dull the senses rather than a stimulant to moral feeling.

And yet the emergent taste culture was far from universally celebrated. For every reviewer who bemoaned the treacly sentiment of Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm or Pollyanna, there were others who railed against the vulgarity of modern literary and popular culture. For example, Edward Wagenknecht describes Lillian Gish’s pale, “Dresden doll” complexion as “immensely precious: doubly so because she lives in an age when . . . everything must be frank and open, everything ruthlessly displayed, no matter how ugly it may be.”17 Indeed, Lea Jacobs understands the debates over the censorship of the movies, debates that were a key element of both Pickford’s and Temple’s stardom, to be a manifestation of the controversies that emerged alongside the new taste culture. “In my view,” writes Jacobs, “the problem censorship posed for the industry was not simply one of enforcing a particular moral agenda but also, and more importantly, of negotiating very different sets of assumptions about the subject matter deemed fit for inclusion in a film and the manner in which it could be represented: it was an issue of decorum as much of morality.”18

Pickford and Temple walked a fine line between these two taste cultures. On the one hand, they tapped into what Raymond Williams would term the “structures of feeling” associated with Victorian values, which were threatened by modern life.19 One reason their films were so successful was that they appealed to the Victorian tastes that had come to be rejected by much of American popular culture. At the same time, though, they also signified American modernity. By updating a stock figure of sentimental fiction, Pickford and Temple suggested that the nation still held to traditional values, that girlhood innocence could thrive even in the soil of modern America.

Just a Grown-Up Child

Despite their shared ability to bridge the divide between Victorian and modern culture and values, Pickford and Temple emerged out of two distinct cultural moments and theatrical traditions. Whereas Temple was often promoted as a prodigy—celebrated for her pre...