- 180 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Revenue Management for Service Organizations

About this book

This book places revenue management at the forefront of management accounting with cost management and performance measurement in supporting roles. Revenue management introduces new ideas such as yield management, while uniting previously disparate subjects such as project management, capacity costing, and the theory of constraints. Methods of pricing and their associated strategies are included as well as techniques for segmenting consumer markets.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Revenue Management: An Overview

Introduction

Revenue management provides organizations with new opportunities to improve their profitability and cash flows. It does this through a combination of sophisticated methods and more refined ways of examining organization processes. We will explain and illustrate these in this book where the focus is on transferring knowledge about revenue management to managers who wish to implement them in practice. Although revenue management is relatively new, whether we know it or not, we encounter revenue management practices almost every day. Consider the following scenarios.

- A two-star hotel with 120 rooms has two rates: a high rate of $200 per night and a discount rate of $110 per night. Ideally, management would like to have all rooms occupied at $200 per night (the full rate), but this may not be achievable. Assume that the reservations manager receives a booking request 1 month in advance for a room at the discount rate of $110. Should she accept the booking at the lower rate or wait, in the hope that a booking at a higher rate will eventuate? If she rejects the booking, the room may remain unoccupied. If she accepts the booking, the hotel may have to turn down a booking at the higher rate.

- A popular restaurant is always full in peak periods but makes only mediocre returns. Food costs appear to be excessively high and although waiting times for customers are extensive in peak times, the restaurant is usually well below 50% occupancy in the remaining opening times.

- An accounting firm struggles to meet deadlines and to provide speedy turnaround responses to its clients. Delays are common, and clients are increasingly upset over the service the firm provides. In response, the firm argues that all clients are treated equally and delays are due to increased compliance requirements imposed by the government.

All three scenarios contain opportunities for improvement through revenue management. The chapters in this book describe how you can achieve this. Airlines, hotels, amusement parks, restaurants, and golf courses are just some of the organizations that have made substantial gains in profitability through practicing revenue management. Former American Airlines chairman and CEO Robert Crandall described revenue management as the most important technical development in transportation management since deregulation of the airlines. Many organizations practicing revenue management claim to have increased revenues substantially. A recent story about pricing baseball tickets like airline seats in BusinessWeek1 quotes the San Francisco Giants’ ticketing chief as stating that the adoption of a new revenue technology could add $5 million or more to the revenue for 2010.

Revenue management aims to improve an organization’s performance by obtaining the best revenue streams possible from its resources. This involves balancing revenue initiatives with managing processes and resources. There is little point in improving one process if this is outweighed by the deterioration of others. Virtually any organization can profit from revenue management.2 In this book, we show you how to apply new techniques and insights that provide the opportunity to improve revenue flows while controlling costs and investment.

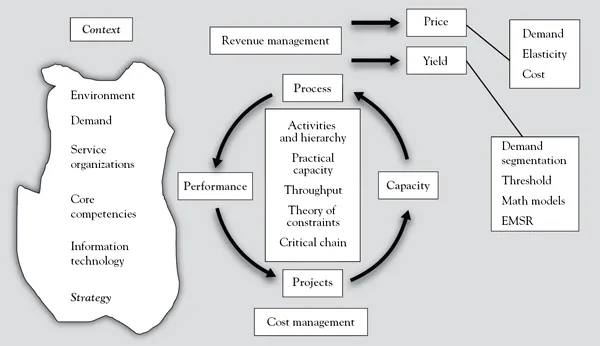

It is not just about maximizing revenue but also about managing resources and related costs of both usage and investment. Figure 1.1 shows a broad picture of the key components that we address in this book. We shall use the three scenarios to illustrate these components.

The first scenario relates to the price and yield components on the right-hand side of Figure 1.1. In turn, these involve the factors in the box. Since there are two prices or rates for the same room, the hotel has segmented its customers into two types: those who are price sensitive and those who are not. By introducing different requirements for each (e.g., to obtain a discounted price, the room must be booked at least 3 weeks in advance), the hotel has created two separate products in the minds of its customers even though the room itself remains unchanged. Ideally, the hotel would like to rent all its rooms at the higher price, but this is unlikely. Consider two extremes: if the hotel refuses to rent any discounted rooms, it is likely to end up with unoccupied rooms. This means lost revenue. If it rents all its rooms at the discounted price in advance, there will inevitably be some customers who would have been willing to pay the higher price closer to the night of stay but who are now lost sales because there are no rooms available. The solution is obviously between these extremes and requires balancing a certain sale now at the discounted price with a less-certain sale at the high price closer to the night of the stay. This sounds like the old adage “a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush,” and the methods for dealing with this include the threshold method and some mathematical models. Of the mathematical models, the two that we will describe and explain are expected marginal seat revenue (EMSR), which is the common method used by airlines and hotels, and linear programming. Any organization is able to use any of the models, but this will require information about demand forecasts and segmenting its customer demand into multiple products.

Figure 1.1. Attributes of the supplier product or service

We have all probably experienced the second scenario in the form of either waiting for a table or deliberately choosing to dine outside of peak times to avoid the rush. Figure 1.1 shows a number of revenue management options. In terms of pricing and yield approaches, we can try to manage demand across peak and off-peak periods using devices such as early-bird specials, two-for-one dining, free entertainment, or even discounted menu prices. These methods are visible to customers but need additional marketing efforts if they are to be effective. An alternative is to look for opportunities to improve the restaurant’s processes. For example, the length of time or duration a table is occupied determines how many times the table can be “turned” (i.e., different sets of diners within a certain time period). The shorter the duration, the more times the tables turn, and the greater the number of customers the restaurant can serve. But customers may not like to feel that they are being hurried during their meal, particularly if they are in a restaurant that they have chosen to celebrate a special occasion. The strategy of the restaurant determines the actions taken. If a restaurant has positioned itself as an exclusive location specializing in fine dining, then its best action is to use pricing to manage peak and off-peak demand. However, even in this situation, there are some actions that the restaurant can take to manage duration. For a restaurant that is medium-priced and caters to diners who want to eat in a pleasant environment but who are less concerned about the specialness of the occasion, a number of options for managing duration are available. Examples include streamlining the menu in peak times, training the waiting staff to avoid suggestive selling during peak times, and “guiding” customers into menu selections that can be more easily filled by the kitchen, thereby reducing preparation time. The secret to duration management is to reduce time spent on activities that are not perceived as adding value to the customers, such as waiting time between servings.

While most of us would recognize the first two scenarios, we do not experience the third scenario quite so often, as we tend to use professional firms less frequently than restaurants or hotels. Nonetheless, many professional organizations experience these problems, and Figure 1.1 shows some of the ways in which revenue management can provide solutions. The mention of deadlines invokes comparison with construction projects, and service organizations can use the same management principles and methods as those used in project management. Furthermore, the major task facing any service business is managing its capacity and capabilities. The theory of constraints, discussed in Chapter 4, uses the idea of a bottleneck to focus on improving its throughput (the rate at which clients are processed and revenue is earned). A bottleneck is the resource or process whose capacity is the primary restriction on how fast volumes can be produced or processed. Often, the bottleneck is a person who authorizes the work or provides a specialization or skill that every job must go through. Mapping the processes and the sequence of these processes can identify bottlenecks as well as reveal potential areas for improvement.

We refer to Figure 1.1 throughout this chapter and the remainder of this book. The important message at this stage is that although revenue management covers many areas, we can boil them down to those that are externally based or visible to the outside world (pricing and yield management) and those that are internally based and not so visible (processes, performance, cost management, and capacity). Revenue management is an all-encompassing approach to the management of the revenue, expenses, and investment areas of an organization. In some ways, it is an old idea repackaged into powerful concepts and techniques that can dramatically improve an organization’s financial performance.

On the subject of old ideas, two centuries ago in 1849, Dupuit wrote on the subject of trains:

It is not because of the few thousand francs which would have to be spent to put a roof over the third-class carriages or to upholster the third-class seats that some company or other has open carriages with wooden benches. What the company is trying to do is prevent the passengers who can pay the second-class fare from traveling third-class; it hits the poor, not because it wants to hurt them, but to frighten the rich3 (quoted by Ekelund).4

This book focuses on the items displayed in Figure 1.1 and explains them using nontechnical language as much as possible. We occasionally resort to more technical terms when this is unavoidable and accompany them with suitable explanations for the benefit of the reader. We also try to minimize technical calculations by putting these inside a sidebar that we have labeled, “Where does the number come from?” You, the reader, can ignore these sidebars without interrupting the flow of the discussion.

This book does not cover all areas. It is not a book about finance or marketing, and although we discuss costing systems, it is not a book about accounting, either. Although information systems are a key feature of many revenue management systems (think airlines), we do not describe these. Similarly, we do not describe sophisticated methods of yield management involving complex mathematical programming and statistical methods. We aim to acquaint the reader with the basic ideas behind revenue management and to provide references for those wishing to pursue the topic in more depth. We also envisage that many managers do not want to understand all the technical details but do want to have a broad understanding of how it works in order to be able to converse with the technical experts. In the chapters that follow, we provide numerous examples in describing the technical material but maintain a high-level perspective on where this material fits into revenue management. If you get lost, come back to Figure 1.1, which shows the main areas of revenue management within an organization. We explicitly include contextual factors in the organization’s structure, strategy, and environment, as these affect the implementation and operation of revenue management. The other main areas include price and yield, process, projects, performance, and capacity. While these may appear to be distinct, Figure 1.1 depicts significant flows among them. This is the nature of real-life systems, which makes them interesting phenomena to study. It also provides a holistic view of how organizations function and enables us to show how techniques within each area interact and complement each other. We briefly describe each of these areas and refer to the relevant chapter that explains them in greater detail. Before doing this, we explain “willingness to pay,” a fundamental concept that we regularly refer to throughout this book.

Willingness to Pay

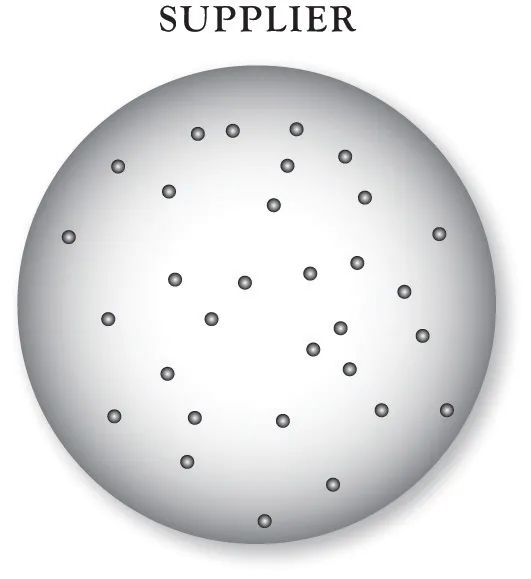

Willingness to pay is a key concept in pricing and yield management, and it underpins many of the issues surrounding value and nonvalue adding that are discussed in later chapters. As the expression suggests, customers vary in how much money they are willing to pay for a product or service. Some customers are willing to pay a high price, while others will purchase only at a lower price. This reflects, to a large extent, the relative value they are placing on a product or service that embodies their perception of the product or service. The diagram in Figure 1.2 represents the features or attributes of a product or service from a supplier perspective. The circle titled “supplier” contains a series of dots that represent product or service attributes, for example, technical features of the product itself, such as functionality, ease of use, reliability, and fit for the job; aesthetic features such as appearance, feel, and attractiveness; and support features such as service, parts, and warranties. These are all attributes that the supplier believes customers value or think that the product or service should contain.

The number of attributes or dots can vary from product to product, although Chapter 3 describes how the same underlying product can be differentiated into many products. Since the supplier knows their product inside and out, they are usually aware of all the bells and whistles that are provided. Suppliers therefore tend to see their products or services differently than customers.

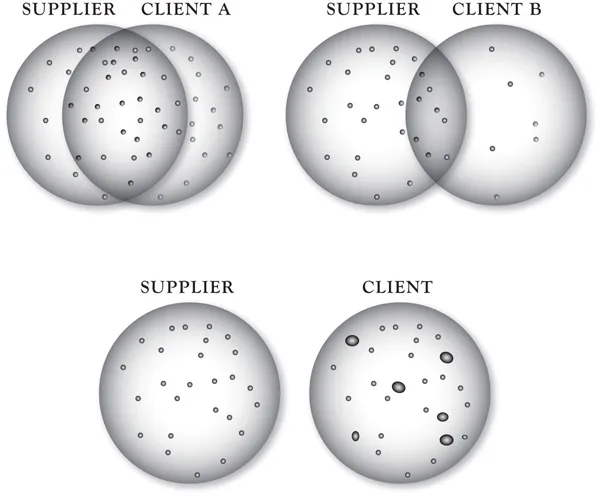

Figure 1.3 shows the interaction of two clients with the supplier and reveals two related dimensions of willingness to pay: (a) clients who do not want all the bells and whistles a supplier provides and (b) clients who value all the supplier product attributes differently.

Figure 1.2. Supplier’s perception of features or attributes of their product or service

Figure 1.3. Willingness to pay as a marriage between supplier and client:

Panel A: Clients only want particular attributes and not others.

Panel B: A client has varying values for the supplier’s product attributes.

In Panel A, two clients are depicted by two respective circles, and these overlap the supplier’s circle. Client A likes many of the attributes provided by the supplier. In contrast, client B only wants some of them. There remain some attributes (to the left of the supplier circle) that both clients either do not want, do not understand how to use, or of which they are simply ignorant. A good example of the latter is the many features found in software packages that are available, but users fail to use them. It is also apparent that the supplier fails to meet all the expectations or needs of clients A and B, represented by the area on the right of the circles. These areas provide an opportunity for the supplier to work with the client to co-create a new product or service that provides greater value to both parties.

Panel B illustrates how a client values the product attributes differently, as shown by the relative size of the dots in the right-hand circle. The larger the dot, the greater the value placed on that attribute. The smaller the dot, the lower the value placed on the attribute. Some attributes are not valued at all, and a careful comparison will reveal where a dot that appears in the supplier’s c...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Revenue Management: An Overview

- Chapter 2: Relating Your Business to Its Environment: Building Strategy From Internal and External Analysis

- Chapter 3: Pricing Strategies and Yield Management

- Chapter 4: Process Management

- Chapter 5: Cost and Capacity Management

- Chapter 6: Performance Measurement

- Chapter 7: Summary

- Notes

- References

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Revenue Management for Service Organizations by Paul Rouse in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Managerial Accounting. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.