This paper argues the case for the adoption of account management programmes by first recognizing that all firms in business-to-business markets have a relatively small number of customers (current and potential) that are critical for long-run future health. Because they are so important, the firm should treat them better than it treats its average customer. It further argues that traditional go-to-market strategies are under pressure from a range of environmental and customer-related factors, leading to fragmentation of the traditional system, and that this system will remain but two additional systems are forming – for small customers and for key, strategic and global customers. For the effective implementation of KAM programmes companies must achieve agreement or congruence between the four key organizational elements of strategy, organizational structure, systems and processes, and human resources.

Introduction

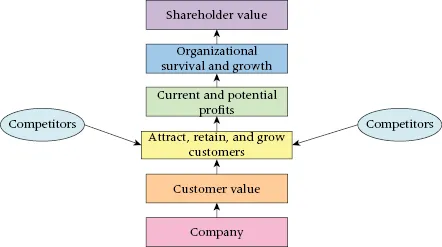

The best place to start in making the case for managing strategic accounts in a business-to-business (B2B) environment is with the fundamental business model (Figure 1). This model assumes that the basic operating task for managers and their companies is to make profits today and promise profits tomorrow. If the firm is successful in this task, it will survive and grow, and shareholder value will increase. However, if the firm is unsuccessful in making profits for a sufficiently long time period, it will eventually go bankrupt and likely be forced out of business. Hence, consistent operating success in making profits enables the firm's survival and growth, and leads to enhanced shareholder value.

The managerial imperative to make profits is all well and good, but the causal relationships laid out in the top part of Figure 1 beg an important question: What does the firm have to do to make profits today and promise profits tomorrow? The answer is extremely simple but very powerful: the firm must attract, retain and grow customers. The firm succeeds in this task by delivering value to customers – the vertical dimension of the figure. But merely delivering value to customers is insufficient. The value that the firm delivers must be greater than the one its competitors deliver so that it may secure differential advantage. Securing differential advantage provides the firm with some level of monopoly power (Lerner 1934) and allows it to earn profit margins that exceed the going interest rate.

It is all well and good for the firm to secure differential advantage and to attract, retain and grow customers, but all customers are not equal; some customers are more equal than others (Orwell 1945). The customer revenue distributions of most firms are skewed, following a Pareto distribution (Davis 1941) – more popularly known as the 80:20 rule. In this formulation, 80% of the firm's sales revenues derive from 20% of its customers. Of course, this rule is not exact: for some firms the ratio may be 70:30 and for others 90:10, or even more skewed. (And we should not just confine ourselves to current customers; some customers that provide small revenues today may join the 20% important customers within a few years.)

The implication for the firm is quite straightforward: if a large percentage of revenues derive from a small percentage of customers, then those relatively few customers should receive a disproportionately large amount of firm attention and resources. But where should the firm locate these resources? That is also quite straightforward: if the 80:20 (70:30) rule is true, then the 20:80 (30:70) rule must also be true – 20% of firm revenues derive from 80% of the firm's customers. In general, these 80% of smaller customers are less important to the firm's future than the 20% of larger customers; hence, they should receive less attention and resources. For many managers, this is a harsh truth to stomach, but they cannot escape the reality that resources are scarce. Unless they accept and act on this reality, they will be condemned to the fate of one well-known company. A senior sales manager famously said of this organization: ‘The problem we face is that senior management doesn't seem to understand the implications of the 80:20 rule; they want us to be fair to all of our customers. The result is quite predictable; we give the same lousy service to all our customers.’1

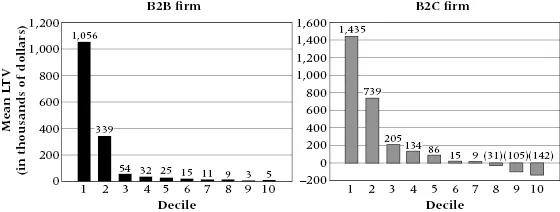

We can move beyond revenue distributions and even profit distributions to consider customer lifetime value (CLV) (Capon 2012). CLV is the expected discounted profit stream the firm earns from a customer factored by the retention rate/probability. Figure 2 shows empirical results from two firms: a B2C firm and a B2B firm (Kumar and Shah 2009). The y-axis measures CLV; the x-axis classifies firms by deciles – largest 10%, second 10%, etc. The figure shows that for both firms, the CLV distribution is highly skewed (in excess of 90:10); the top two customer deciles are responsible for CLV for each firm. For the B2B firm, CLV just declines as customer deciles become smaller. For the B2C firm, the eighth, ninth and tenth customer deciles incur losses.

To summarize: all firms have a relatively small number of customers (current and potential) that are critical for long-run future health. Because they are so important, the firm should treat them better than it treats its average customer. This admonition may sound unfair, but it is absolutely necessary. However, all firms have traditional organization structures and processes for addressing customers that may have been in place for many years but do not recognize the new reality. In this paper, we present these traditional systems, we discuss the various pressures they face, then we show the ways in which many firms are evolving their go-to-market approaches. These new systems recognize the realities of the fundamental business model and the Pareto distribution that characterizes their revenue sources, and attempt to address their weaknesses in this new and evolving world.

Addressing customers

Most B2B firms' traditional approach to addressing customers typically embraces some form of personal selling effort. The basic choice that firms make is to conduct this activity in-house with an employee sales force or by outsourcing the selling effort to third parties such as agents, brokers, representatives and/or distributors. When the firm decides to conduct the selling effort itself, it must trade off selling effort effectiveness with the cost of sales. Typically, the least costly approach is to organize the sales force by geography – each salesperson sells all of the firm's products to all customers within a well-defined geographic area. However, if customer needs and/or product characteristics vary widely, this approach may not be very effective. For this reason, the firm may specialize its sales effort organizationally by product, market segment, distribution level, current versus potential customers, or some other dimension. Indeed, a large firm may employ multiple types of sales specialization.

The crucial point is that all firms have some traditional sales organization in place. Certainly the organization evolves over time, but historically, firms have not considered customer importance as a key dimension on which to organize. To put it bluntly, the implications of the fundamental business model and the Pareto revenue distribution discussed above have not deeply penetrated many executive suites. But this is changing and in the next section we suggest some critical pressures that are causing firms to think more deeply about their go-to-market strategies and to make significant changes.

Generalized pressures on traditional go-to-market strategies

Regardless of the historic success of the particular go-to-market model the firm currently employs, four general areas – increased competition, environmental forces, globalization and sales force costs – are generating increased pressure on the firm.

Increased competition

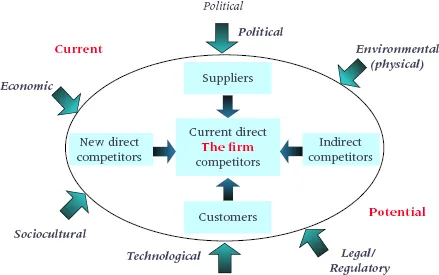

There is scarcely any executive today who will tell you that the competitive environment is easing – virtually all will agree that competitive pressures are increasing in depth and scope. The best approach to competitive pressures is to adapt Porter's five forces model (Porter 1980) and consider each of the forces he identified as a competitor (current or potential). In this framework the firm faces five types of competitors:

Traditional direct competitors. These competitors target similar customers to the firm with similar products and services, and similar business models, according to established rules of the game. Typically, neither the firm nor its competitors gain advantage quickly; rather, improved positions result from long-run sustained effort. Regardless, more rapid change may occur when direct competitors merge, or resource availability shifts quickly via acquisitions/divestiture, leveraged buyouts and new capital structures.

New direct competitors. These competitors also offer similar products and services but often have some new competitive advantage. Many Western corporations face competition from Asian firms; these new direct entrants often secure price advantage based on low-cost labour. Sources of new direct entrants may be start-ups including former firm employees, firms expanding geographically, organizational networks, new sales and distribution channels, and strategic alliances.

Indirect competitors. These competitors offer similar customer values to the firm but with quite different products or technologies. These functional substitutes often appear as different product classes or product forms. Examples are legion: Kodak's chemical film versus electronic imaging; bricks-and-mortar bookstores versus Amazon; and steel versus plastic in automobiles.

Supply-chain competition. The firm may face two types of supply-chain competition: suppliers may integrate forward by offering the firm's customers products that the firm currently offers, or the firm's customers may integrate backwards by purchasing from the firm's suppliers and adopting in-house activities the firm currently performs. (Of course, the firm may face severe pressure from suppliers and buyers short of actual competition; we discuss customer pressure in more detail below.)

As a general statement, the overall level of competition faced by most firms is increasing. Different firms face different competitor types and pressures. At any point in time, one competitor or another type may be more significant for the firm. Of course, all firms must consider not only the types and levels of competition they face today but also the potential competitors they may face tomorrow.

PESTLE forces

The firm must address a set of environmental forces that seem ever more complex and subject to change. The PESTLE acronym captures these well: P – political, E – economic, S – sociocultural, T – technological, L – legal/regulatory and E – environmental (physical environment).

Whether it is governmental policy changes, shifting social mores, the impact of the Internet, reregulation and deregulation, or global warming or the fallout from volcanoes in Iceland and Chile, the perturbations caused by PESTLE forces are seriously affecting most firms. Some forces impact the firm directly but, as Figure 3 illustrates, they also have an indirect impact via the firm's competitive environment.

Globalization

A special feature of broad environmental pressures is the seemingly inexorable march towards greater globalization (Friedman 2007). Factors driving increased globalization include a generalized political belief that trade is good; development of organizations such as the World Trade Organization (WTO) to effect increased trade by reducing barriers; the maturing of economic and political unions (like the European Union (EU)) and free trade areas (like NAFTA); greater competitive home-market pressures that encourage firms to venture abroad; opportunities in emerging markets such as BRICI (Brazil, Russia, India, China, Indonesia); improved global communications and the Internet; and improved global transportation – by air for small packages, by sea via containerization, or by widening the Panama Canal.

The combined effect of these factors means that firms conduct increasing amounts of business outside their home-market boundaries. Increas...