![]()

PART I

1

Definitions

1.1. The First Steps

Embarking in 1971 on the organization of the first International Symposium on the Mesolithic in Europe, the author had already published his study of the Polish Mesolithic (“Prehistory of Polish Territories from the 9th to the 5th Millennium BC”, Warsaw: PWN 1972 [in Polish]), as well as ten articles devoted to the Polish Mesolithic (under the common title “The problems of the Polish Mesolithic”). In the territorial sense, these works exceeded the actual borders of Poland, extending from the Elbe in the West to the Dnepr in the East and even further afield. The reason lay not in the author’s sphere of interests alone. It arose from two extensive surveys of available material, covering Moscow, St. Petersburg (then Leningrad), Vilnius, Minsk, Potsdam, Schwerin, Stralsund, Dresden, and Weimar (for the East German visit I remain deeply indebted to Bernhard Gramsch) during which the author had the opportunity to meet with specialists and acquire inside knowledge of many Mesolithic collections, regardless of their importance.

In Poland, this was a time of intensive archaeological research on the Mesolithic and great opportunities for the young and dynamic students of Stefan Krukowski, attending a seminar chaired by Waldemar Chmielewski at the Institute of the History of Material Culture of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw. Poland’s partial opening to the West fruited in exchanges with scholars not only from the Eastern bloc (Carl J. Becker, Hermann Schwabedissen, P.V. Glob, Wolfgang Taute, Hans-Jürgen Müller-Beck and others).

The time was ripe for an overview of the neglected Mesolithic of Europe, starting with the definition (it was then widely believed to be a terminal phase of Late Glacial adaptations) and going on to fundamental description and divisions, not to mention economy. It should be kept in mind that not many specialists in the field were around.

At the time the author was young and ambitious, not to say naïve, and he immediately tried to bite off more than he could chew. His earliest texts presented here are proof of this, where he treats on the definition of the Mesolithic, on a continental system of cultural divisions and extensive cartography. Following these are some texts from later years, which are more balanced and – should I say – less naïve?

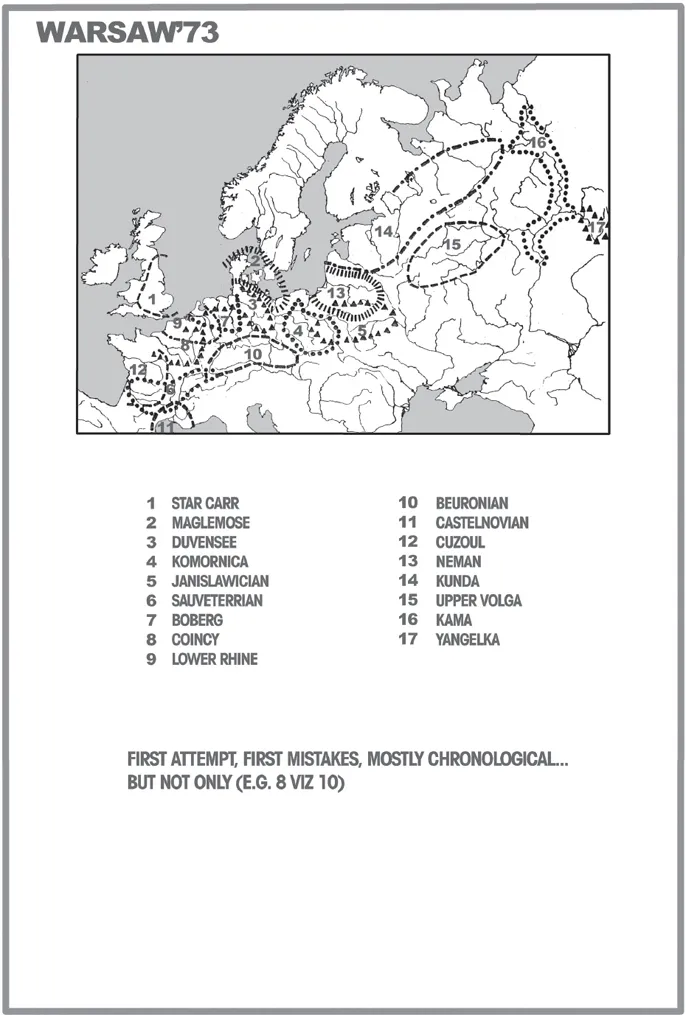

1.2. Warsaw ’73

Introduction to the history of Europe in the Early Holocene

Archaeological literature notes these two basic definitions of the Mesolithic:

A. | The first comprises the prehistoric period between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic (chronological order) upon the assumption that the “Mesolithic” covers the area of the Old World independently of ecological zones and is characterized by cultures of “microlithic” and “geometric” forms of tools. |

B. | The second definition, and I fully support it, restricts the term “Mesolithic” both in area and environment (Fig. 1.2a–b). The word “Mesolithic” is used here in the meaning of an economic-developmental pattern. It is synonymous with the hunting-fishing-gathering economy which had developed in the European Low land (sic SKK in 2006) with the already developed fore station during the Early Holocene. For this reason then it should be appropriate to take the term to mean the “Mesolithic stage of cultural and economic development” which had distinctly been determined by environment but not necessarily circumscribed in time. |

I am of the same opinion as regards the terms “Paleolithic” and “Neolithic”, which should correspond to the respective stages of economic and cultural development. These stages can be variously dated in particular areas, having developed, for instance, parallel to the Neolithic cultures in the Near East and the Epi-Paleolithic and Paleolithic cultures respectively in the Balkans and Scandinavia. Meanwhile some of those stages never took place in other regions, e.g., there was no Neolithic stage in the Early and Middle Holocene forests of Canada and Siberia.

It seems that the Mesolithic stage resulted from the adaptation of Paleolithic tundra communities to the new ecological conditions, that is, to the forest which appeared in the European Lowland (and Western Europe – SKK in 2006) during the Early Holocene. Important environmental changes which took place at the turn of Late Glacial and Post Glacial forced the original inhabitants of the Lowland to emigrate or to adapt. Adaptation meant a switch to the only available kind of economy, i.e., Mesolithic type of economy. In contrast to the Mediterranean countries, the poor soil of the European Lowland did not create favorable conditions for a direct change from the Paleolithic to the Neolithic economy (sic SKK in 2006).

This is why still more emphasis should be laid on the striking ecological change which accounted for the formation of this basically local or regional stage which the Mesolithic in fact was. Similar changes took a long time to occur in North European territories inhabited in the Early Holocene by the Paleolithic communities of reindeer hunters: Hensbacka, Fosna, Komsa and Suomusjärvi. These tundra-to-forest changes occurred earlier south of the Carpathians. In these regions, the forest communities of Mediterranean type had developed since the Late Pleistocene and, with no big changes occurring, they survived into the Holocene (Epi-Gravettian).

Briefly speaking, the Mesolithic is a stage of “WAITING” or “QUARANTINE”, which was realized in an environment where primitive agriculture could not develop.

Comment in 2006

The above text demonstrates the naiveté of the author’s writing in 1973. The Mesolithic or whatever you call that which followed after the Latest Pleistocene in all of Europe and which lasted until the next great supra-regional change, which was the ceramization (cf.) and Neolithization, is not to be described with a single formula apart from a chronological one perhaps (cf. “The Mesolithic: What we know and what we believe”). But “waiting” and “quarantine” sound nice, don’t they?

Observations of the conservative approach of Late Glacial/Early Holocene Balkan and Scandinavian communities remain true today (no important techno-typological evolution or change). The same can now be said of the Early Holocene groups in South Italy and Iberia. From this perspective, the European Lowland appears much more dynamic at the time, and so does the region between the Pyrenees and the Dynaric Alps. (cf. “Rhythms”).

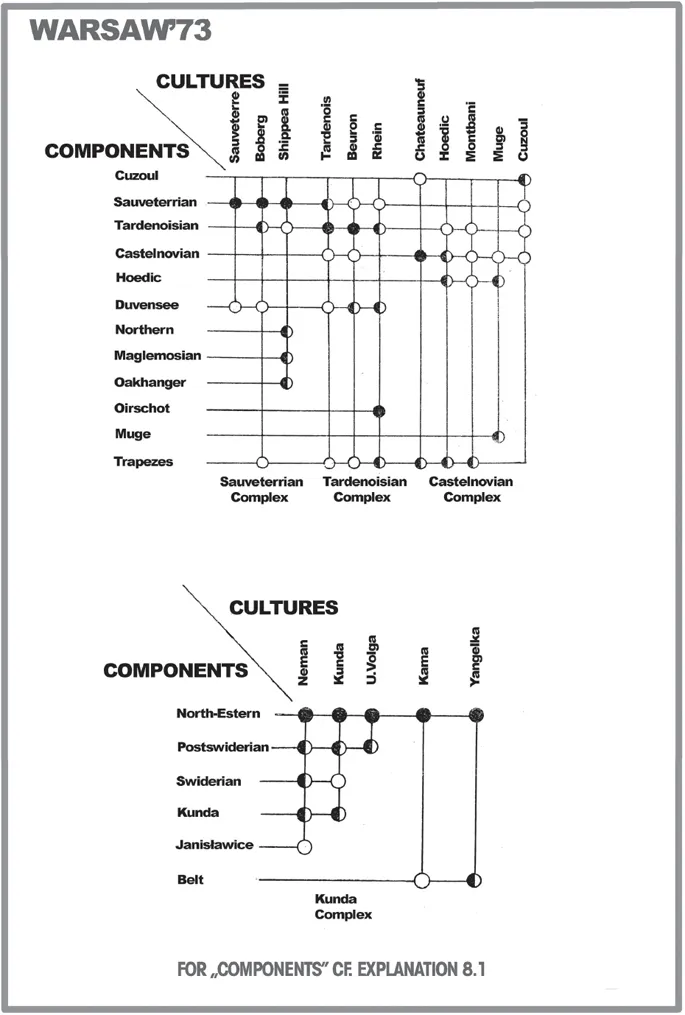

Thirty some years later, the author can say he has gained the wisdom to modify his definition of the Mesolithic from a “behavioral” to a chronological one. It hardly changes the fact that the Early and Middle Holocene were characterized by highly diversified adaptation models. At the beginning of the period, the region between the Pyrenees and the Ural mountains, north of the Alps and south of the North Sea and the Baltic was seething with activity. The southernmost (both in the East and West) and northern extremes of the continent either continued placidly in the old traditions without any breeze of evolution to disturb the picture, or were only starting to be settled by pioneers streaming in from the south who introduced very few changes in their culture. For an explanation of the term “component” used in the figures, cf. “Les courants interculturelles”.

1.3. Forli ’96

Early postglacial adaptations in central Europe

Introduction

The objective of this paper is a concise presentation of selected aspects of communities of hunters, gatherers, and fishermen inhabiting Central Europe (area between the Rhine and Dnieper, and the Baltic and Adriatic) during the Early and Middle Holocene, i.e. from c. 9400/9000 cal. BC to 6300/5600 (Balkan Peninsula and Carpathian Basin) and 5500/3800 cal. BC (Central European Lowland). The earlier date marking the appearance in Central Europe of communities described as “Mesolithic” is similar throughout the area in question (cf. radiocarbon dates for Star Carr in England, Klosterlund in Denmark, Friesack, Duvensee and Jägerhaushöhle in Germany, Romagnano III in Italy, Padina in Serbia, Frankhthi in Greece, Chwalim I and Całowanie in Poland, Pulli in Estonia). Not so in the case of the final dates which differ considerably from region to region (c. 6900 cal. BC for the Balkan Peninsula – Frankhthi; 6350 for Odmut, Lepenski Vir and Vlasac in Serbia and Montenegro; c. 4900 for northern Italy – Romagnano III, Riparo Gaban; c. 5100/4350 for Switzerland and southern Germany, cf. Birsmatten-Basisgrotte, Jagerhaushöhle, Tschäpperfels; c. 5500/4900 for the southern part of the Central European Lowland, but c. 4350/3750 in its northern part, e.g. in Polish Pomerania or in Denmark).

I have begun with a definition of the phenomenon described as ‘Mesolithic’ and have proceeded to discuss the pertinent evidence, the environment which conditioned the formation and existence of this phenomenon, and the differentiation (zonation) of this environment. Further on, I have presented the principal features of the system of adaptation to the described environment, devoting separate attention to regional adaptation systems, particularly to the stylistic differences of flint artifacts, this differentiation being due only partly to ...