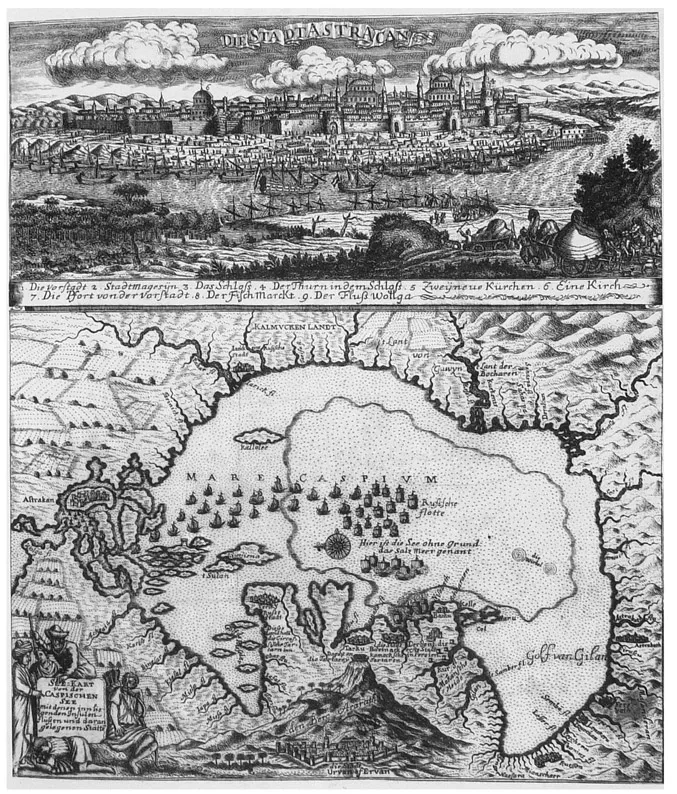

“Vid Astrakhani i karta Kaspiiskogo moria” (View of Astrakhan and the Caspian Sea) (1678), from the German edition of Jan Struys’s Reisen durch Greichenland, Moscau, Tatarey . . . , reproduced in Natal'ia Borisovskaia, Starinnye gravirovannye karty i plany xv–xviii vekov (Galaxy, Moscow, 1992), p. 155.

CHAPTER ONE

Frontier Colonization

As heaven and earth beget them, men have one same heaven, but each a different earth.

Ch'iu Chün, Supplement to the “Expansion of the ‘Great Learning’ ”

THE RUS' LAND AND THE FIELD

According to the Primary Chronicle, when the first Eastern Slavs established themselves in what would become Ukraine and western Russia they settled in woods and along waterways: “So these Slavs came and settled on the Dniepr and called themselves People of the Clearings [poliane]; others called themselves People of the Trees [drevliane] because they settled in the forests; and different ones settled on the Dvina and called themselves People of the Polota [polochane], taking the name of the Polota River, which flows into the Dvina. And those Slavs who settled near Lake Ilmen' called themselves by their own name—Slavs—and they built a town and called it Novgorod [New Town].”1 The chronicler did not indicate why the Slavs chose to settle in these environments and not others, though it was presumably because the surroundings offered fish, shellfish, berries, honey, furs, game, shelter, and fuel as well as security from enemies and opportunities for farming and trade.2 Over time, as the settlers came under the rule of Rus' Varangians “from beyond the sea” and their rulers, centered in the wooded, riverine town of Kiev, adopted a new religion and literary language “from the Greeks,” the Slavs’ habitat as well as their “Slavic tongue,” their “written law,” and their wise decision to forsake the “gloom of idolatry” for “the sunlight of the true faith” became what their Kievan spokesmen saw as their defining attributes.3

Known to the Rus' as “the field” (pole), the grassy plains that opened up to the south of their settlements appeared completely different. In contrast to the “Rus' land” (rus'kaia zemlia), “the field” contained few freshwater lakes or trees, and its inhabitants were nomadic pastoralists who did not speak Slavic, did not farm, had no permanent homes, and had little interest in either “written law” or the Christian god. Instead, as the chronicler put it, they “lived according to the ways of their fathers,” which included such unsavory habits as “shedding blood,” eating carrion and prairie dogs, and sleeping with their stepmothers.4 Most disturbing of all, the nomads periodically raided Rus' towns and ambushed their trading parties on the Dniepr, which meant that they were not merely foul and godless but also dangerous. Kievan ecclesiastics, who began writing in the eleventh century, consequently singled out the Pechenegs, Torki (Oghuz), and especially the Polovtsy (Qipchaq, Cumans), who occupied the steppe during that time, as their country’s most heinous neighbors. Indeed their heinousness was so complete that Rus' authors did not conceive of them as members of the inhabitable world made by God (oecumene) but rather as the descendants of apocalyptic peoples (such as the Ishmaelites and the unclean tribes of Gog and Magog) whose eventual victory against the Christians would herald the end of the world.5 A “pagan place” where their “meek and suffering” monkish brethren were taken away to be tortured and their “brave princes” went to do battle with the “godless armies of the Polovtsians,” the plains were the Kievan literati’s ultimate wilderness: “the threatening antitype to [their] ordered cosmos” and the “ultimate disquieting horizon of [their] medieval world.”6

This was the world according to the churchmen. The world of day-today interaction was different. Relations between the Rus' and the nomads were in fact intimate as well as distant, and peaceful as well as hostile, with physical proximity creating its own rules of engagement. Southern Rus' settlements on the fringes of the forest-steppe could be as little as a few hours’ ride from habitual nomadic pastures and encampments. (According to one early eleventh-century account, it took two days to travel by horse from the town of Kiev to the edge of the “land of the Pechenegs.”)7 Consequently, Rus' princes and commoners went to “the field” to hunt bison, boar, hare, fox, and antelope or to break wild horses, while the nomads went to Rus' towns to trade, receiving honey, cloth, grain, and metal goods in exchange for horses, cattle, sheep, and hides, all of which, according to the Byzantine emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus, were much appreciated by the Rus' since “none of the aforesaid animals is found in Russia.”8 The Rus' and the nomads were also tied through the Rus'-sponsored trade “from the Varangians to the Greeks,” which crossed the steppe and consequently depended on the nomads’ cooperation for its success.

Whenever the Rus' refused to provide the nomads with the “gifts” they expected, or the nomads broke their arrangements with the Rus' by raiding Rus' towns to seize slaves and other “booty,” the trade suffered, but such hostilities were rarely prolonged enough to shut the trade down completely.9 Instead, quite the opposite occurred. The trade endured and the dependencies it created turned the nomads and the Rus' into essential players within each other’s fractious politics, with a necessary blurring of distinctions between the two sides. By the late twelfth century, Rus' princes married nomadic “princesses” and vice versa; alliances were formed between Rus' and Polovtsy clans against the clans of other Rus' and nomads, and no one had a monopoly on raiding. In his Testament, the Kievan prince Vladimir Monomakh relates attacking his Rus' rivals with “his Polovtsy,” being raided by “the whole Polovtsian land” as well as their Rus' allies, rescuing certain “Polovtsian princes” from their Polovtsian captors, and, in another instance, capturing three Polovtsian princes and some fifteen notables alive and then “cut[ting] them down and throw[ing] them into the Sal'nia River.”10 This was right after the prince noted that he had also “made peace with the Polovtsian princes once less than twenty times, both in my father’s day and after his death [i pri otse i bez otsa], and I gave [to them] many of my clothes and heads of stock.”11

The most obvious physical example of the complicated consequences of cohabitation was the stretches of earthen ramparts and palisades that the Rus' began building south of their settlements in the time of Vladimir the Great and Iaroslav the Wise. Known to subsequent Slavs as “serpentine walls” (zmievye valy), the intended purpose of the ramparts was to keep the nomads from raiding Rus' towns, as well as to keep the lands between the walls and the towns from being turned into nomadic pasture.12 The defenses were also recognized as an obvious dividing line between the “Rus' land” and “the field.” As the archbishop Bruno put it, having passed through the gates in an attempt to proselytize among the nomads in 1008, on one side of the ramparts lay the territory of Prince Vladimir while on the other was the land of “his enemy . . . the Pechenegs . . . the most evil of pagans.”13 Yet if the walls were intended as an “ordering concept,” their practical impact was at best disorderly.14 They never stopped either the Rus' or the nomads from crossing into each other’s territory when political or economic objectives required it (that is, neither party saw the ramparts as an obstacle to an “offensive strategy”), and because various Rus' rulers made use of nomadic allies as border guards and servitors, the defenses ultimately brought the Rus' and the nomads together as much as they kept them apart.15 The walls were not part of a deliberate policy to colonize the land behind them nor were they used as a springboard for taking over “the field,” since the rulers of Rus' conceived of their dominion in terms of “the peoples that render Rus' tribute” rather than in terms of territorial possession.16 And in any case, taking over the steppe was not a realistic proposition. Even if the Rus', as the beneficiaries of an agricultural economy, were in a position to depend less on the nomads than the nomads depended on them, neither “the field” nor the “Rus' land” could overwhelm the other with convincing military superiority.17

THE WILD FIELD AND THE TSARDOM

This rough parity collapsed in 1223 when the Rus' and their Polovtsy allies were routed by an army of “unknown peoples” (iazytsi neznaeme) on the steppe near the Kalka River.18 The “unknown peoples” turned out to be the Mongols, who, some twenty years later, leading one of the largest steppe confederations ever assembled, destroyed Kiev and turned the Rus' into tributaries. This fact at once solidified the Rus' ecclesiastics’ loathing of “the field” (identified now with “these godless Moabites called Tatars”) and completely changed Rus' politics.19 The nomads were now in charge, so much so that the khans of the Golden Horde gradually began settling into a stationary capital on the Lower Volga.20 Kiev was eclipsed, and the obscure principality of Moscow, much further north and deeper within the woods, gradually became the new center of the Rus' lands. As Moscow “rose,” its princes paid the tribute to the khans, gave them hostages, and were alternatively obedient and rebellious as circumstances allowed. Once the Horde began to unravel, Moscow maintained similarly complicated relations with its fellow successor states, the Turko-Mongolic and Islamicized khanates of Kazan, Crimea, and Astrakhan. Muscovite rulers fought with the khanates over Tatar raiding and slave-taking, took sides in their internal politics, and made claims to patrimonial entitlement. But they also sent embassies seeking “friendship and love,” recruited Tatar servitors, and engaged in a good deal of commerce. Long-distance merchantmen like Afanasii Nikitin of Tver' shuttled goods between Muscovy and “the Derbent Sea—the Sea of Khvalinsk” and “the Black Sea—the Istanbul Sea,” while Muscovite nobles, or boyars, yearly exchanged furs, cloth, and walrus tusks for thousands of horses from their Nogay (Mangyt) “friends” and “brothers” on the Volga steppes.21 In other words, the familiar realpolitik continued. Conflict with people the churchmen called “evil beasts” and “godless creatures,” now all the more heinous for having adopted Islam, did not preclude cooperation, and not even growing commitments to Orthodox messianism could eclipse the worldly pursuits of stability and profit.22

This remained the case even after the armies of Ivan IV conquered the town of Kazan in 1552. Pragmatism in relations with the steppe continued, only now the presumption was that Moscow alone should be in charge. During the next four years, the men of Ivan Vasil'evich subju-gated the rest of Kazan’s territory, and in the summer of 1556, with the aid and encouragement of their allies among the Nogays, they seized the poorly defended entrepot of Astrakhan at the mouth of the Volga and chased out the independent “Astrakhan tsar,” replacing him with a Nogay khan obedient to Moscow.23 Next, the leaders of the Bashkir (Bashkort) clans, former tributaries of Kazan and the Nogays in the Southern Urals, “beat [their] foreheads” and agreed to submit to Muscovite rule in the 1550s. So, too, did the khanate of Sibir' (later conquered outright by Moscow in 1581). Using Astrakhan as a base, the tsar’s men then pushed around the western end of the Caspian and into the Northern Caucasus, building scattered forts and insisting on the fealty of local “princes.”24 Of course, even as the Muscovites “gathered” these remnants of the former Horde, they could not and did not even try for a full sweep by acquiring the Crimea or the north Pontic steppe, inhabited by the Nogay Lesser Horde, who were “vassals” of the Crimeans. Instead, the Crimeans, themselves “vassals” of the Ottomans, joined a Turkish-led and ultimately ill-fated “expedition against Astrakhan” in 1569. Then, two years later, they organized their own, much more success...