CHAPTER 1

Hypotheses, Laws, and Theories: A User’s Guide

What Is a Theory

Definitions of the term “theory” offered by philosophers of social science are cryptic and diverse.1 I recommend the following as a simple framework that captures their main meaning while also spelling out elements they often omit.

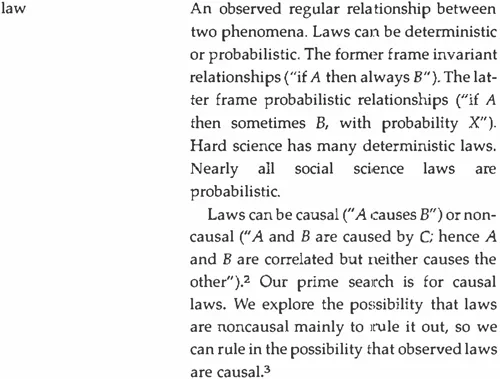

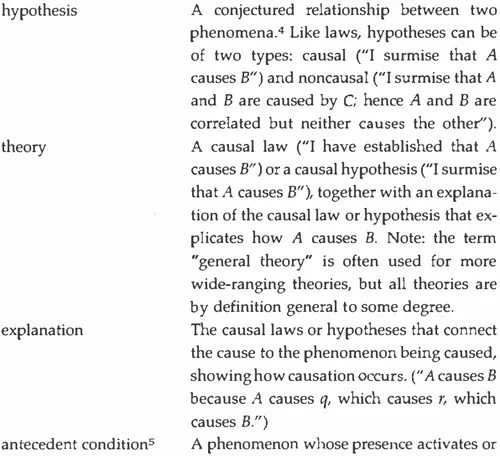

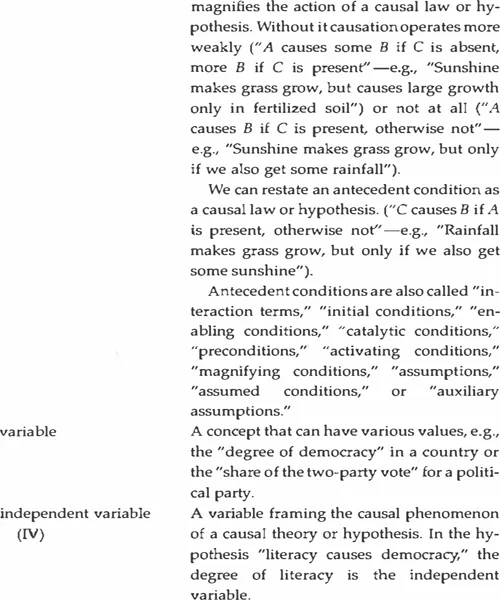

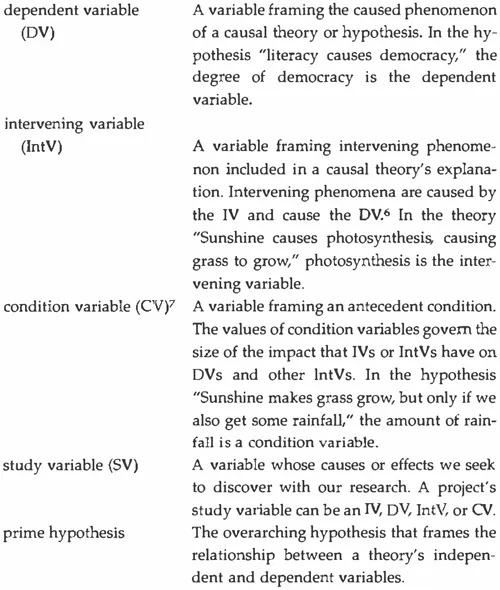

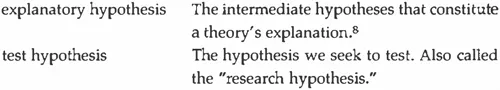

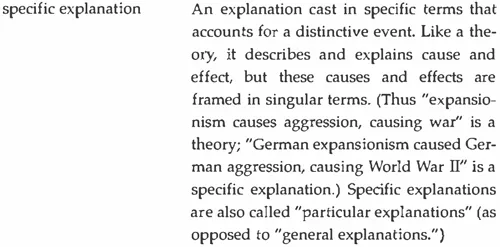

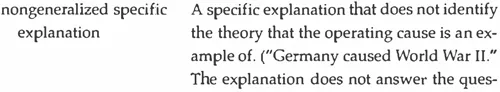

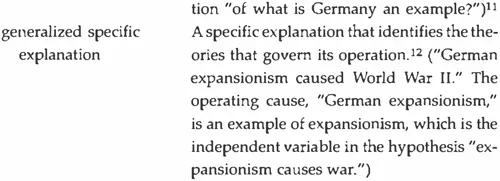

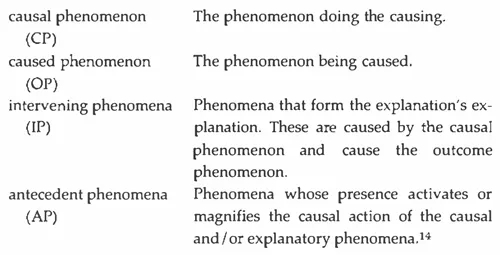

Theories are general statements that describe and explain the causes or effects of classes of phenomena. They are composed of causal laws or hypotheses, explanations, and antecedent conditions. Explanations are also composed of causal laws or hypotheses, which are in turn composed of dependent and independent variables. Fourteen definitions bear mention:

Note: a theory, then, is nothing more than a set of connected causal laws or hypotheses.9

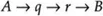

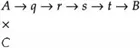

We can always “arrow-diagram” theories, like this:

In this diagram A is the theory’s independent variable, B is the dependent variable. The letters q and r indicate intervening variables and comprise the theory’s explanation. The proposal “A → B” is the theory’s prime hypothesis, while the proposals that “A → q,” “q → r,” and “r → B” are its explanatory hypotheses.

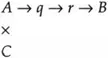

We can add condition variables, indicating them by using the multiplication symbol, “×.”10 Here C is a condition variable: the impact of A on q is magnified by a high value on C and reduced by a low value on C.

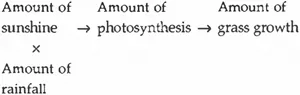

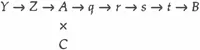

An example would be:

One can display a theory’s explanation at any level of detail. Here I have elaborated the link between r and B to show explanatory variables s and t.

One can extend an explanation to define more remote causes. Here remote causes of A (Y and Z) are detailed:

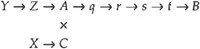

We can detail the causes of condition variables, as here with the cause of C:

There is no limit to the number of antecedent conditions we can frame. Here more conditions (D, u, v) are specified.

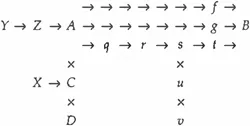

One can add more avenues of causation between causal and caused variables. Here two chains of causation between A and B (running through intervening variables f and g) are added, to produce a three-chain theory:

A “theory” that cannot be arrow-diagrammed is not a theory and needs reframing to become a theory. (According to this criteria much political science “theory” and “theoretical” writing is not theory.)

What Is a Specific Explanation?

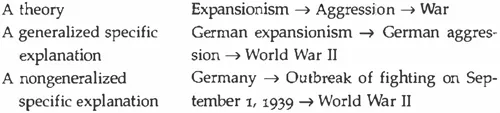

Explanations of specific events (particular wars, revolutions, election outcomes, economic depressions, and so on) use theories and are framed like theories. A good explanation tells us what specific causes produced a specific phenomenon and identifies the general phenomenon of which this specific cause is an example. Three concepts bear mention:

Specific explanations come in two types. The second type (“generalized specific explanation”) is more useful:

Specific explanations are composed of causal, caused, intervening, and antecedent phenomena:13

We arrow-diagram specific explanations the same way we do theories:

What Is a Good Theory?

Seven prime attributes govern a theory’s quality.

1. A good theory has large explanatory power. The theory’s independent variable has a large effect on a wide range of phenomena under a wide range of conditions. Three characteristics govern explanatory power:

Importance. Does variance in the value on the independent variable cause large or small variance in the value on the dependent variable?15 An important theory points to a cause that has a large impact—one that causes large variance on the dependent variable. The greater the variance produced, the greater the theory’s explanatory power.

Explanatory range. How many classes of phenomena does variance in the value on the theory’s independent variable affect, hence explain? The wider the range of affected phenomena, the greater the theory’s explanatory power. Most social science theories have narrow range, but a few gems explain many diverse domains.16

Applicability. How common is the theory’s cause in the real world? How common are antecedent conditions that activate its operation? The more prevalent the causes and conditions of the theory, the greater its explanatory power.17 The prevalence of these causes and conditions in the past govern its power to explain history. Their current and future prevalence govern its power to explain present and future events.

2. Good theories elucidate by simplifying. Hence a good theory is parsimonious. It uses few variables simply arranged to explain its effects.

Gaining parsimony often requires some sacrifice of explanatory power, however. If that sacrifice is too large it becomes unworthwhile. We can tolerate some complexity if we need it to explain the world.

3. A good theory is “satisfying” that is, it satisfies our curiosity. A theory is unsatisfying if it leaves us wondering what causes the cause proposed by the theory. This happens when theories point to familiar causes whose causes, in turn, are a mystery. A politician once explained her election loss: “I didn’t get enough votes!” This is true but unsatisfying. We still want to know why she didn’t get enough votes.

The further removed a cause stands from its proposed effect, the more satisfying the theory. Thus “droughts cause famine” is less satisfying than “changes in ocean surface temperature cause shifts in atmospheric wind patterns, causing shifts in areas of heavy rainfall, causing droughts, causing famine.”

4. A good theory is clearly framed. Otherwise we cannot infer predictions from it, test it, or apply it to concrete situations.

A clearly framed theory fashions its variables from concepts that the theorist has clearly defined.

A clearly framed theory includes a full outline of the theory’s explanation. It does not leave us wondering how A causes B. Thus “changes in ocean temperature cause famine” is less complete than “changes in ocean temperature cause shifts in atmospheric wind patterns, causing shifts in areas of heavy rainfall, causing droughts, causing famine.”

A clearly framed theory includes a statement of the antecedent conditions that enable its operation and govern its impact. Otherwise we cannot tell what cases the theory governs and thus cannot infer useful policy prescriptions.

Foreign policy disasters often happen because policymakers apply valid theories to inappropriate circumstances. Consider the hypothesis that “appeasing other states makes them more aggressive, causing war.” This was true with Germany during 1938–39, but the opposite is sometimes true: a firm stand makes the other more aggressive, causing war. To avoid policy backfires, therefore, policymakers must know the antecedent conditions that decide if a firm stand will make others more or less aggressive. Parallel problems arise in all policymaking domains and highlight the importance of framing antecedent conditions clearly.

5. A good theory is in principle falsifiable. Data that would falsify the theory can be defined (although it may not now be available).18

Theories that are not clearly framed may be nonfalsifiable because their vagueness prevents investigators from inferring predictions from them.

Theories that make omnipredictions that are fulfilled by all observed events are also nonfalsifiable. Empirical tests cannot corroborate or infirm such theories because all evidence is consistent with them. Religious theories of phenomena have this quality: happy outcomes are God’s reward, disasters are God’s punishment, cruelties are God’s tests of our faith, and outcomes that elude these broad categories are God’s mysteries. Some Marxist arguments share this omni-predictional trait.19

6. A good theory explains important phenomena: it answers questions that matter to the wider world, or it helps others answer such questions. Theories that answer unasked questions are less useful even if they answer these questions well. (Much social science theorizing has little real-world relevance and thus fails this test.)

7. A good theory has prescriptive richness. It yields useful policy recommendations.

A theory gains prescriptive richness by pointing to manipulable causes, since manipulable causes might be controlled by human action. Thus “capitalism causes imperialism, causing war” is less useful than “offensive military postures and doctrines cause war,” even if both theories are equally valid, because the structure of national economies is less manipulable than national military postures and doctrines. “Teaching chauvinist history in school causes war” is even more useful, since the content of national education is more easily adjusted than national military policy.

A theory gains prescriptive richness by identifying dangers that could be averted or mitigated by timely countermeasures. Thus theories explaining the causes of hurricanes provide no way to prevent them, but they do help forecasters warn threatened communities to secure property and take shelter.

A theory gains prescriptive richness by identifying antecedent conditions required for its operation (see point 4). The better these conditions are specified the greater our ability to avoid misapplying the theory’s prescriptions to situations that the theory does not govern.

How Can Theories Be Made?

There is no generally accepted recipe for making theories.20 Some scholars use deduction, inferring explanations from more general, already-established causal laws. Thus much economic theory is deduced from the assumption that people seek to maximize their personal economic utility. Others make theories inductively: they look for relationships between phenomena; then they investigate to see if discovered relationships are causal; then they ask “of what more general causal law is this specific cause-effect process an example?” For example, after observing that clashing ef...