- 582 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A complete, professional resource for writing an effective paper in all subfields of political science, Diane Schmidt's 25th anniversary edition provides students with a practical, easy-to-follow guide for writing about political ideas, events, policies, passions, agendas, and processes. It offers additional formats and guidelines focusing on the growing use of social media and the need for professional communication in blogs, tweets, forums, media sites, lectures on demand, and postings on websites. A collection of student papers shows students how to write well for better grades.

After reading Writing in Political Science students will know how to:

- choose and narrow a research topic;

- formulate a research agenda;

- quickly locate reputable information online;

- execute a study and write up findings;

- use the vocabulary of political science discourse;

- follow the criteria used to evaluate student assignments when writing;

- apply writing skills to an internship, civic engagement project, or grant proposal; and

- manage and preserve achievements for career development.

New to the Fifth Edition

- Locating Research Materials: Updated links to all sources, expansion of appropriate sources to include mobile sources available through tweets, blogs, forums, and other informal communication; expansion of tools to include database searching; use of smart phone technology; and evaluation of source reliability to include commercial sources, Wikipedia, media sites, social media, and lectures on demand.

- Creating Evidence: Evaluating data sources on the web including government databases, non-profits, and special interest/commercial data; and using collaborative forms of data collection. Includes a new section on Memorandums of Conversations (MEMCON), essential in recent political controversies.

- Manuscript Formatting and Reference Styles: Updated examples of citing internet sites, blogs, forums, lectures on demand, and YouTube.

- Format/Examples: Updated exam-writing treatment to include on-line, e-learning, open-book exams, media applications examples using YouTube and online media; restored legal briefs treatment; revised proposal examples; revised PowerPoint instructions to include diversity considerations; expanded formula for standard research papers to include wider disciplinary treatment, expanded communication techniques, format and examples of appropriate posting for social media and organizational websites, expanded internship treatment, inclusion of needs-assessment format and examples.

- Career Development: Restoration of 3rd edition chapter and expansion of professional portfolio building including vitae, resume, cover letters, letters of intent, statement of purpose, and skills/competency discussions.

- Updated citations for changes in The Chicago Manual of Style, 17th Edition, 2017 and The MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers, 8th Edition, 2016.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Writing in Political Science by Diane E. Schmidt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Political Inquiry

This writing guide is designed to help students sharpen, reinforce, and develop good writing and research habits in political science. Writing is a process through which we learn to communicate with others. No one expects students to be perfect writers. We all learn and help each other learn. Through organization, writing, and rewriting drafts, and logical presentation of our ideas, we engage in an intellectual process that helps us grow and be a part of the discourse community of political science.

What the Guide Is Supposed to Do

1. Sharpen writing skills particular to political science.

2. Provide information about standards and expectations concerning political science writing.

3. Help differentiate between writing for political science and other disciplines.

What the Guide Cannot Do

1. This material does not teach primary writing skills.

2. This material is not intended to be a substitute for a formal class in writing.

3. This material will not teach grammar, spelling, or punctuation.

4. This material cannot substitute for poor preparation.

THE ART OF POLITICAL INQUIRY DEFINED

Many students are unaware that writing assignments for political science classes require different skills from those required for English composition, creative writing, and journalism courses. Although the basic skills are the same, political scientists, as members of a discipline:

• Ask different questions and seek different answers to questions than those of the humanities and physical sciences.

• Are interested in more than a description of what happened, where something happened, or when something happened.

• Are interested in the political process or the causal connections between political events.

An event or a phenomenon must be politically relevant for it to be of interest to political science scholars. Of course, the standard definition of what is politically relevant is often in the eye of the beholder! A general rule for writing in political science classes is for students to always ask, before they write anything: What are the politics or power relationships existing in a political event?

Professional Research

Professional research in political science is based on the acquisition of scientific knowledge. Locating scientific knowledge requires developing or applying theories either through induction (based on observations) or deduction (based on prior expectations). According to Jones and Olson (2004), such theories include:

1. Systems Theory: This theory explains political activities as part of a process or system. Researchers using this theory explain political phenomena by examining elements in the political environment (citizen activism, parties, interest groups, etc.).

2. Power Theory: This theory explains political activities by examining the power relationship between individuals or groups.

3. Goals Theory: This theory explains political activities by examining the purpose or goals of political phenomena.

4. Rational Choice Theory: This theory explains political activities as a result of individuals’ preferences and self-interest.

Professional Methods of Investigation

There are a variety of approaches to examining political phenomena and there are a number of student paper examples that approximate these professional approaches.

Philosophical method: Those using this approach examine the scope, purpose, and values of government activity. Often, those using this method ask how policymakers should act. This approach is inherently deductive (see “Example of a Political Argument” in Chapter 2 and “Example of an Analytical Essay” and “Example of an Editorial” in Chapter 10).

Historical method: Those using this approach examine what conditions contributed to the occurrence of government activity. The focus of this research is on the structure of a historical event and how this structure may condition the outcome of future events (see “Example of an Analytical Case Study” in Chapter 14).

Comparative method: Those using this approach compare and contrast experiences of governments, states, and other political entities (see “Example of a Comparative Paper” in Chapter 12).

Juridical method: Those using this approach examine the legal or procedural basis for government activities. This approach is sometimes also referred to as institutional research (see “Example of a Legislative Analysis” in Chapter 13).

Behavioral method: Those using this approach study the behavior of political actors by examining data collected on actual political occurrences. Often referred to as positivism or empiricism, this value-free approach approximates the scientific method to examine causal relationships and test theories on actual events (see “Example of an Analysis” in Chapter 12 and “Example of a Policy Evaluation” in Chapter 13).

Post-behavioral method: Those using this approach examine, sometimes with mathematical models, not only observed behavior but values associated with the behavior. Often referred to as post-positivist, this method supports the argument that examining values and ethics, as well as observed events, is important (see “Example of a Position Paper” in Chapter 12 and “Example of a Policy Recommendation” in Chapter 13).

For more information on political inquiry in political science, policy, and public administration, see Jones and Edwards (2005), Schrems (2004), and Rabin (2003).

TYPES OF STUDENT WRITING

Although professional-level research is rarely expected of students, political science assignments often emulate professional research. The following is a list of common types of writing assignments required in political science classes.

Analysis: These assignments usually ask students to examine the relationships between the parts of a political document or some political events or political outcome. Typically, these assignments require the student to provide a perspective or reasoned opinion about the significance of an event or a document (such as a policy). For example, students may be required to assert and defend an opinion about the most important features in the Bill of Rights (see examples in Chapter 12).

Argument: These assignments often require the student to prove or debate a point. Typically, these assignments ask for normative assertions supported by evidence and examples. For instance, instructors may ask students to provide an argument supporting (or not) automatic voter registration, random drug testing, or a constitutional amendment protecting the flag (see “Example of a Political Argument” in Chapter 2 and “Example of an Analytical Essay” in Chapter 10).

Cause and effect: These assignments typically require the student to speculate about the reasons why some political event has occurred. For example, students may be asked why people vote, why members of Congress worry about their images, what caused the Civil War, or why some people are disillusioned with government (see “Example of an Analysis” in Chapter 12).

Classify: These assignments usually ask the student to identify a pattern or system of classifying objects, such as types of voters, types of political systems, or types of committees in Congress (see “Example of a Literature Review” in Chapter 12).

Compare or contrast: These assignments usually ask the student to identify the differences and similarities between political roles, political systems, or political events (see “Example of a Comparative Paper” in Chapter 12).

Definition: These assignments usually ask the student to define a political concept, term, or phrase such as democracy, socialism, or capitalism. Students must provide examples of distinguishing features and differentiate the topic from others in its functional class (see “Sample Answer: Essay Test Question” in Chapter 10).

Process: These assignments usually ask the student to describe how some political phenomena relate functionally to other political phenomena. For example, students may be asked to describe how media influence voting behavior, how decisions are made in committees, or how a historical event occurred (see “Example of a Position Paper” and “Example of Process Tracing” in Chapter 12).

THE PROCESS OF POLITICAL INQUIRY

Professional political scientists, as part of a discourse community, engage in a process of political inquiry that involves using research techniques, critical thinking skills, and theory building. In general, political inquiry involves posing a question (a hypothesis), collecting data, analyzing the data, and drawing conclusions about whether the data support the hypothesis.

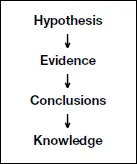

Understanding the nature of evidence and uses of data to support an assertion or hypothesis is critical to the inquiry process. The process functionally relates questions to evidence to conclusions to knowledge:

A hypothesis is a generalization that can be tested. Hypotheses state expected relationships between the dependent variable (the event being explained) and the independent variables (occurrences that caused or are associated with causing the event). Most importantly, hypotheses assert precisely how a change in the independent variable(s) changes the dependent variable.

Data are evidence. There are two kinds of data:

Quantitative evidence: objective or numerical data usually from surveys, polls, tests, or experiments.

Qualitative evidence: subjective or authoritative data usually from interviews, firsthand observations, inference, or expert opinions.

Conclusions are assertions made by the author concerning the relationship between the hypothesis and the evidence.

Knowledge is what we have learned from political inquiry. The goal of all political inquiry is to contribute to a universal body of knowledge. As scholars, we are obliged to learn and contribute to this body of knowledge.

Problem Solving, Learning, and Writing

One of the most important components of political inquiry is the creative process that students engage when moving from abstract ideas to concrete assertions about the nature and scope of political problems. As students form arguments about the relationships between variables, they engage in several iterations of action-based learning that move from divergence (sorting information) to convergence (recombining information) in developing their arguments about political events (Ninck 2013). From this sorting and recombining process, students should develop the following active learning results:

Outcomes based on sorting (divergence)

Evaluation: assessing the value, significance, or worth of the event. Analysis: examining events systematically.

Reflection: using thoughtful consideration of how what is learned can be used to improve the future.

Outcomes based on recombining (convergence)

Synthesis: combining different perspectives about the event into a single idea.

Understanding: explaining what is learned.

Application: applying what is learned to a new event (also known as transference).

The Author’s Argument: The Nature of Assertions

Sometimes, in conversation with friends and colleagues, we take for granted that assertions or statements are true or are reasonably close to being correct. Sometimes we even switch from opinions to beliefs to facts as th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Detailed Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Political Inquiry

- 2 Critical Thinking: The Cornerstone of Political Inquiry

- 3 Topic Selection

- 4 Locating Research Materials Using Indexes, Databases, the Internet, and Mobile Sources

- 5 Creating Evidence with Primary and Secondary Data

- 6 Properties of a Good Essay or Research Paper

- 7 Common Problems with Writing

- 8 Practices and Expectations for Manuscript Format

- 9 Referencing Styles for Author-Date and Footnote/Endnote Systems

- 10 Format and Examples of Activities to Enhance Comprehension and Synthesis of Class Materials

- 11 Format and Examples of Assignments for Managing and Processing Information

- 12 Format and Examples of Conventional Research Papers

- 13 Format and Examples of Assignments Requiring Special Techniques

- 14 Format and Examples of Assignments with Appropriate Formatting for Professional Communication

- 15 Format and Examples of Assignments Organizing and Documenting Achievements for Career Development

- Text Acknowledgments

- Index