![]()

PART ONE SEX IN THE CITY

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

Ernest Boulton, aka Stella or Lady Stella Clinton

Frederick William Park, aka Fanny Winifred

Lord Arthur Pelham Clinton, Conservative member of Parliament,

third son of the Duke of Newcastle

Louis Hurt, well-connected employee of the post office in Scotland

John Safford Fiske, American consul at Leith

Mr. Flowers, judge at the Bow Street Magistrates’ Court

Hugh Alexander Mundell, idle gentleman, admirer of Stella

Francis Kegan Cox, businessman, admirer of Stella

George Smith, former beadle at the Burlington Arcade

Dr. James Thomas Paul, police surgeon

Amos Westrop Gibbings, gentleman, host at the ball at Haxell’s Hotel, the Strand

Mrs. Mary Ann Sarah Boulton, mother of Ernest

Judge Alexander Park, father of Frederick

Lord Chief Justice Alexander Cockburn

Simeon Solomon, artist

John Saul, eponymous hero of The Sins of the Cities of the Plain,

or Confessions of a Mary-ann

Various and sundry policemen, lawyers, physicians, partygoers, landladies,

domestic servants, a theater manager, a coachman, a hotel proprietor, an actor,

and numerous anonymous reporters and editorialists

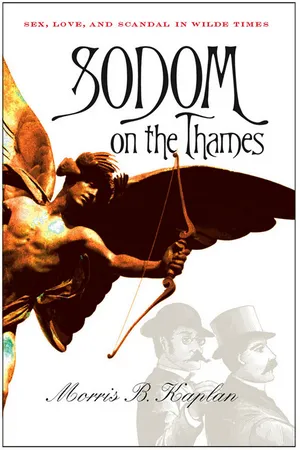

1. “MEN IN PETTICOATS”

The presence in London of sites where men looking for sex with other men might congregate was not new in the 1860s. However, this underworld might have become more easily accessible to men such as Symonds who did not set out deliberately in search of it. This enhanced visibility reflected both the proliferation of urban forms of life and the emergence of a heightened consciousness of erotic possibility among middle-class men. Symonds’s narrative of his encounters unsettles any easy division between private and public domains: the urban landscape he charts is at once personal fantasy and social reality. Occasionally, the police would interrupt such casual encounters between men in squares, parks, and public lavatories, leading to prosecutions for sodomy, attempted sodomy, or “indecent assault.” The visibility of female prostitution had become a subject of increased public concern as the nineteenth century progressed, and young working-class men willing to exchange sexual favors for ready cash were also not hard to find: guardsmen had a special reputation in that regard. Sometimes these episodes became police matters when complaints of assault were countered by allegations of attempts at blackmail.

“Molly Clubs,” where men looking for other men gathered, date back to the beginnings of the eighteenth century.1 Perhaps the most notorious was “Mother Clap’s Molly House.” The constable who brought charges against it in 1726 testified:

I found between 40 and 50 Men making Love to one another, as they call’d it. Sometimes they would sit on one another’s Laps, kissing in a lewd Manner, and using their Hands indecently. Then they would get up, Dance and make Curtsies, and mimick the voices of Women. . . . Then they’d hug, and play, and toy, and go out by Couples into another Room on the same Floor, to be marry’d, as they call’d it.2

There were men dressed as women: “Some were completely rigged in gowns, petticoats, headcloths, fine laced shoes, furbelowed scarves, and masks; some had riding hoods; some were dressed like milkmaids, others like shepherdesses . . . and others had their faces patched and painted and wore very expensive hoop petticoats, which had been very lately introduced.”3 Most often the “marriage” was nothing more than a one-night stand, but there are some reports of longer-term relationships. In 1728, a blacksmith called “Moll Irons” wed a butcher attended by two “bridesmaids”: “Princess Seraphina the butcher of Butcher Row and Miss Kitten (alias Mr. Oviat, ‘who lately stood in the pillory’).”4 More puzzling are reports that some of the mollies enacted mock childbirths surrounded by their friends.

These clubs had been known to exist since around 1700 and their owners and patrons were intermittently prosecuted by representatives of the Societies for the Reformation of Manners and officials sympathetic to their cause. These trials could have dire consequences: Of those arrested at Mother Clap’s establishment, “three men had been hanged at Tyburn, two men and two women had been pilloried, fined and imprisoned, one man had died in prison, one had been acquitted, one had been reprieved, and several had been forced to go into hiding.”5 These cases received considerable publicity in newspapers and pamphlets; public outrage at those arrested sometimes erupted into fatal violence. The last such scandal, involving the “Vere Street Coterie” in 1810, led to a near riot when the London crowd went after six men sentenced to the pillory: “The first salute received by the offenders was a volley of mud, and a serenade of hisses, hooting and execration, which compelled them to fall flat on their faces in the caravan. The mob, and particularly the women, had piled up balls of mud to afford the objects of their indignation a warm reception.”6 Whereas earlier, most mollies came from the working class, those caught up in the Vere Street affair represented a broader social mix. Some men of wealth were believed to have bribed their way out of trouble.7

By the middle of the century, such scenes were long forgotten. Those Molly Clubs that survived were pretty much left to their own devices. The mollies were content to entertain themselves. Their notoriety resulted from the efforts of reforming moralists, often aided by individuals with grudges to settle, to clean up particular neighborhoods. Something important happened when these figures of flagrant effeminacy and suspect desire emerged from protected enclaves and began walking the streets openly. This “coming out” challenged conventional assumptions about gender and sexuality, domesticity and publicity, commerce and pleasure. The Yokel’s Preceptor, a London publication of the 1850s, warns visitors to the city of new dangers, thus whetting the appetites of those with unconventional tastes or restless desires:

The increase of these monsters in the shape of men, commonly designated margeries, poofs, etc., of late years, in the great Metropolis, renders it necessary for the safety of the public that they should be made known. . . . Will the reader credit it, but such is nevertheless the fact, that these monsters actually walk the streets the same as whores, looking out for a chance!8

The guide identifies parts of the city that offered such sights and opportunities, including the Strand, the Quadrant, Holborn, Charing Cross, Fleet Street, St. Martin’s Court. The author mentions individuals who plied their trade in these parts, one of whom, known by a woman’s name, kept a “fancy woman” of his own. He paints a vivid portrait of their gathering places, appearance, and distinctive gestures: “They generally congregate around the picture shops, and are to be known by their effeminate air, their fashionable dress. When they see what they imagine to be a chance, they place their fingers in a peculiar manner underneath the tails of their coats, and wag them about—their method of giving the office.”9 It is hard to imagine Symonds responding to such a sign the way he did to the young grenadier or the phallic graffito. The spectacle of Victorian London offered and inspired a variety of erotic possibilities.

The most notorious incident combining gender transgression and same-sex desire is the case of Ernest Boulton and Frederick Park in 1870–1871.10 Their flagrant appearance on the scene as “Stella” and “Fanny” was discomfiting enough to get them arrested. Boulton and Park, the sons, respectively, of a stockbroker and a judge, were initially charged with offending “public decency” by repeatedly parading about London’s West End dressed in women’s clothes and followed by groups of young men. Both their respectable social origins and their very public promenades distinguished them from the mollies of earlier times. The case received extensive publicity that revealed how powerfully the “men in petticoats” amused and troubled the imagination. Witnesses claimed to believe they were women, responding to them as especially flagrant—and attractive—female prostitutes.

Agitation about street prostitution in England’s cities and concern about the threat of contagion had been marked in the preceding years. The Contagious Diseases Acts of 1864, 1866, and 1869 tried to control the spread of venereal disease among the armed forces by authorizing both police and physicians in selected naval ports and army garrisons to detain women suspected of being “common prostitutes.” These women were subjected to intrusive medical examinations and could be confined in hospitals against their will for up to six months. After their release, their health was regularly monitored. If they failed to cooperate, they could be jailed. This intense regulation of young women and the apparent approval of male sexual license generated increasing opposition from moral reformers, early feminists, and political radicals who condemned the disproportionate impact of the acts on the working classes. Public agitation led to the repeal of these provisions in the 1880s. As for London, visitors from abroad frequently commented on the large number of streetwalkers offering their services at the city’s center.11 Thedisplay of sexual opportunities in public spaces was seen as a threat to bourgeois domestic virtue, a threat embodied in women whose “painted faces” disguised the contagion they carried.

To these dangers Fanny and Stella added subversion of the “natural” order of sex and gender. At the same time, the two young men appeared in court as scions of the respectable upper middle class, represented by distinguished barristers who claimed they were performers who had allowed their youthful pranks to get out of hand. Prosecution efforts to show that they earned their living as prostitutes were confounded by evidence about their income and class status. Ironically, the attempt to discipline and punish these privileged miscreants became a spectacular performance before an audience greater than any they might have imagined.

The case began with Boulton’s and Park’s arrest at the Strand Theatre in late April 1870 and culminated in their trial before the Lord Chief Justice and a special jury at the Queen’s Bench, Westminster Hall, in May 1871. After an extended hearing in the Bow Street Magistrates Court that attracted crowds of onlookers and extensive press coverage, they were indicted and tried for “conspiracy to commit the felony” of sodomy. It turned out that the authorities had been watching Fanny and Stella for more than a year. After taking the pair into custody as they left the theater in full drag, accompanied by a young swell, police searched their rooms and confiscated a large quantity of women’s apparel, jewelry, photographs, and personal letters. The police surgeon subjected the two to intrusive physical examinations analogous to those authorized by the Contagious Diseases Acts for suspected female prostitutes.12 Their letters revealed the existence of a circle of friends who shared a coded language, played fast and loose with gender norms, and raised suspicions about deviant desires and sexual practices. Police traced two of their correspondents to Edinburgh, where they conducted similar searches leading to the indictment of Louis Hurt and John Safford Fiske. Witnesses were produced who had seen Fanny and Stella in drag at theaters and restaurants, at the annual Oxford-Cambridge boat race on the Thames, and at a fancy dress ball. On several occasions authorities had ejected them from the Burlington Arcade, the Alhambra Theatre, and other public places because of the commotion they created. Boulton and Park generated a pervasive confusion about their gender. Although newspapers proclaimed righteous indignation at their behavior, they could not disguise their fascination with these exotic figures. Hugh Alexander Mundell, the “idle” gentleman and son of a barrister arrested with them, admitted that when first he met them, they wore men’s clothes; still, he insisted he had taken them to be women in disguise. When they protested they were men, this young man-about-town simply refused to believe them. Of course, there is no reason to accept the self-serving testimony of an admirer—given under the threat of legal prosecution. Fanny’s and Stella’s ambiguous displays of feminine and masculine characteristics may have been among their principal charms.

The public attention paid to the case of Boulton and Park suggests that the appearance of men in women’s clothes around the West End was still a novelty. Cross-dressing was not established in the public mind as an indication of same-sex sexual desire. When he charged the defendants with “conspiracy to commit the felony” of sodomy in addition to the less serious “offense against public decency,” the prosecutor undertook to establish that link. Sodomy had been defined as a capital crime by the Buggery Act of Henry VIII in 1633 and remained one until 1861, when the penalty was reduced to life imprisonment. (No executions for sodomy are reported after 1836.)13 Judges had defined the “sin not to be named among Christians” as anal intercourse, regardless of the sex (or species) of the partner, and required proof of penetration. As both active and passive partners were equally guilty, this evidence was not easy to find. The more frequent charges were “attempted sodomy” and “indecent assault.”14 Until the 1830s, men convicted of these crimes could be exposed in the “pillory” where, as in the Vere Street case, angry crowds might vent their outrage by hurling garbage and offal at them. Some were permanently injured or mutilated by these expressions of community morality.15 Against this background, the decision to charge Fanny and Stella with felonies seriously raised the stakes, mobilizing family and friends in support of the accused men. It also heightened public interest in the story.

The way of life and intimate relations of Boulton, Park, and their friends were subject to intense and protracted scrutiny and were reported in extensive detail in the major newspapers under headlines such as “Men in Petticoats,” “The Gentlemen Personating Women,” or “The Young Men in Women’s Attire.” More extravagantly, others announced “The ‘Gentlemen-Women’ Case” or “The ‘Men-Women’ at Bow Street.” The illustrated papers included vivid portraits of the two, both in and out of drag. (At the time of their trial, they appeared as well-dressed young men-about-town: Fanny had even grown whiskers, and Stella a faint mustache.) Public appetite for scandal in high places was whetted by claims that Stella had lived as the “wife” of an aristocratic young member of Parliament, carrying visiting cards that announced her as “Lady Arthur Clinton.”

The case was vigorously contested; the defendants were represented by leading barristers of the day. They offered evidence that Boulton and Park were actors who took women’s roles in both amateur and professional theatricals. The well-financed defense team called eminent professors of medicine to testify to the innocence of the men’s bodily condition and to challenge “expert” testimony on the effects of repeated acts of sodomy. The uncertainty regarding the significance of Fanny’s and Stella’s female impersonations permitted even the most sober ...