- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

With its prominent profile recognizable for miles around and featuring vistas among the most beloved in the Appalachians, North Carolina’s Grandfather Mountain is many things to many people: an easily recognized landmark along the Blue Ridge Parkway, a popular tourist destination, a site of annual Highland Games, and an internationally recognized nature preserve. In this definitive book on Grandfather, Randy Johnson guides readers on a journey through the mountain’s history, from its geological beginnings millennia ago and the early days of exploration to its role in regional development and eventual establishment as a North Carolina state park. Along the way, he shows how Grandfather has changed, and has been changed by, the people of western North Carolina and beyond.

To tell the full natural and human story, Johnson draws not only on historical sources but on his rich personal experience working closely on the mountain alongside Hugh Morton and others. The result is a unique and personal telling of Grandfather’s lasting significance. The book includes more than 200 historical and contemporary photographs, maps, and a practical guide to hiking the extensive trails, appreciating key plant and animal species and photographing the natural wonder that is Grandfather.

To tell the full natural and human story, Johnson draws not only on historical sources but on his rich personal experience working closely on the mountain alongside Hugh Morton and others. The result is a unique and personal telling of Grandfather’s lasting significance. The book includes more than 200 historical and contemporary photographs, maps, and a practical guide to hiking the extensive trails, appreciating key plant and animal species and photographing the natural wonder that is Grandfather.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One: A History of the Mountain

Chapter 1: Grandfather Mountain

NATURALLY OUTSTANDING

You expect inspiring shapes from the world’s iconic mountains. The elegant obelisk of the Matterhorn leaps to mind. At Grandfather, it’s the mountain’s signature profiles that put an acclaimed public face on this summit. Grandfather’s distinctive patriarch is truly set in stone. Seen from both east and west, the mountain’s highest ridge forms a figurative face looking skyward. Another profile gazes upward above Foscoe on the northwest ridge of Calloway Peak, from the summit to near NC 105. The most remarkably human face looks west from the lowest outcrop, the “beard” or “chin” of that bigger visage. With the sad loss of New Hampshire’s “Old Man of the Mountains” on May 3, 2003, the anthropomorphic crown of the Appalachians settled solely on Grandfather. Actually—no slight intended to the North Country—it was already there. Grandfather had its face-based name before surveyors first sighted New Hampshire’s Old Man in 1805. More than that, Grandfather’s faces are more dramatic, more humanlike than the Old Man of New Hampshire’s memory—and license plates still. But Grandfather’s significance extends beyond a pretty face or four. Its profiles adorn a massive mountain that stands alone on the skyline at the crest of the Blue Ridge.

Grandfather’s impressive massif drops east from snow-dusted mountain ash and full blown autumn on the peaks to still-green forests far below in the Piedmont. Photo by Randy Johnson.

Geology of Grandfather Mountain

The geological term “window” may be unfamiliar, but in the case of the “Grandfather Mountain window” the concept draws the curtain on real insight into how this iconic mountain came to be. A geological window is where a layer of rock has eroded or broken open to expose a lower layer. Generally, a “window is an opening through younger rocks that permits a look back at older rocks below the surface,” explains Anthony Love, a geologist and geology department researcher at Appalachian State University in Boone. In Grandfather’s case, the upper layer is actually the older rock, the Linville Falls thrust sheet. A “hole” has formed in that upper layer—the Grandfather Mountain window—through which we see younger rock that accounts for Grandfather Mountain’s ruggedness today. Grandfather’s window is a triangular oval almost 50 miles long and as much as 20 miles wide. It’s a big chunk of terrain that misses Boone but includes Linville and Linville Gorge.

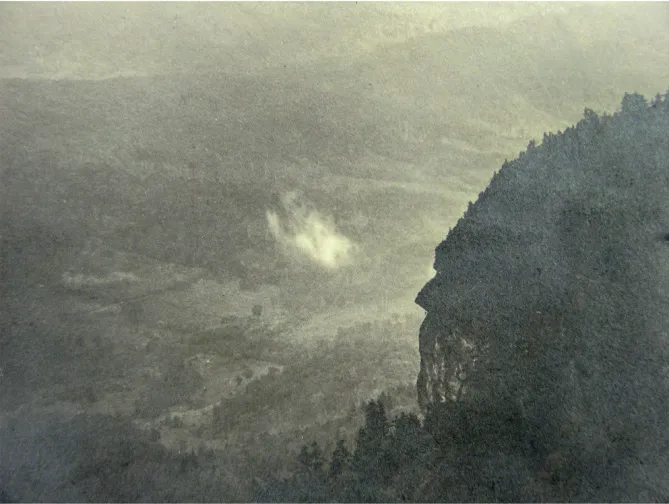

Faces abound on the Grandfather Mountain, and they’ve been photographed and commented on for centuries. Early hiker D. R. Beeson captured this iconic image of the authentic Grandfather Profile in 1913. Courtesy of Archives of Appalachia, East Tennessee State University, D. R. Beeson Papers.

That window makes Grandfather Mountain a great vantage point from which to appreciate how the grandeur of the Appalachians started and why so much of it remains on this special summit. “There are few places on Earth where so many people can ascend to the crest of a mountain range formed by the collision of continents,” writes Robert J. Lillie in a Blue Ridge Parkway geology treatise. And there is “no other where they can drive the length of the crest.” That’s well known to geologists at Appalachian State, where students and researchers have been studying the Grandfather window for years. “The big hurdle we face as scientists,” Love laments, “is that our research is so laced with technical terms that it isn’t simple to explain.” Nevertheless, both Love and his colleague Dr. Loren Raymond, former geology department chairman, are experts on Grandfather Mountain’s geology. Both men are drawn to it for more than scientific reasons—Raymond and his family to the rugged trails, and Love to Rough Ridge, one of the state’s best rock-climbing sites. Each insists the creation of the Appalachians and the head-scratching concept of the Grandfather window are easy to understand if you don’t get too technical. The key is plate tectonics, the notion that earth’s surface consists of meandering sheets of crust and upper mantle—the lithosphere—that float atop softer, warmer matter called the asthenosphere. The collisions of those shifting plates have shaped the globe we spin on today, and the mountain we look up at. About 1 billion years ago, the collision of Africa and North America (an early continent called Rodinia) pierced the sky with peaks as high as the Alps or Himalayas. That earliest mountain-building event created what Raymond calls the “roots of Grandfather Mountain,” distinctly different types of rock called gneiss that, adds Love, “contain the same minerals as granite; it’s just been metamorphosed, squashed out, and compressed.” Wilson Creek gneiss, Blowing Rock gneiss, and Cranberry gneiss were all formed between 1.2 and 1 billion years ago from sedimentary or igneous rocks during the intense heat and pressure of metamorphism, a force unleashed by the mountain-building collision that raised summits up and down the ancient continent’s east coast. Love calls them “basement rocks”—the lowest structural level of the Blue Ridge and “some of the oldest rocks in the Appalachians.”

Those “early” Appalachians, the Grenville Mountains, were ultimately eroded by water, wind, snow, and ice. As the tectonic plates that caused the collision spread apart, blocks of rock dropped down, and a continental rift zone, or rift valley, formed below, eventually filling up with layer upon layer of sediment eroded from higher ground. Love describes that process as you might see it today on the scale of a small mountain stream, where an endless cycle of rains and floods generates silt and sand, layers of mud populated with pebbles and big rocks from above. Raymond calls that sediment-covered plain “the Grandfather Mountain Basin.” The multilayered part of that plain that would “become the rocks of Grandfather Mountain” eventually “solidified to become rocks called conglomerate (former gravels), sandstone (former sands), and shale (former muds),” Raymond explains. Offers Love, “Grandfather Mountain’s biggest contribution is that this is one of the oldest mountain-building events that we can easily recognize on the East Coast, where it’s apparent that the continent was being torn apart—forming the basin and the sediments that eventually became Grandfather.” Ultimately, as Rodinia separated, an early North American continent, Laurentia, was on its own between 770 million and 600 million years ago. Cracks formed in the sedimentary surface left behind, and until about 740 million years ago, lava flows filled in the cracks with ancient eruptions. This three-quarter-billion-year-old material was the earliest form of the rock that would become Grandfather Mountain.

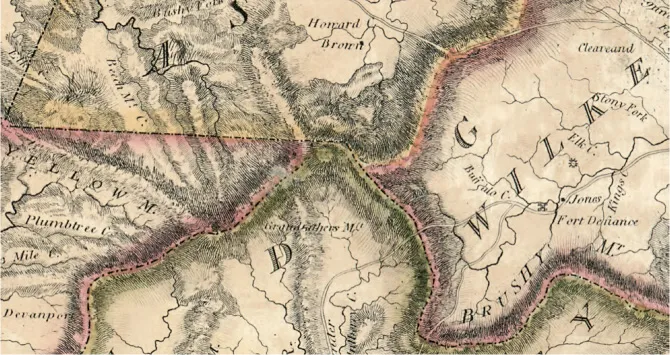

The earliest land grants bestowing ownership of property on or near the mountain in the late 1780s were already referring to the peak as Grandfather. By 1808, a possessive version of the mountain’s anthropocentric name—“Grandfather’s Mountain”—had made itself onto this early map in the Library of Congress, dubbed the “Price-Strother Map; First Actual Survey of North Carolina.” Note that the landmarks at the time were not towns but the family-named farms of early, often noteworthy, backcountry settlers. North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina Library at Chapel Hill.

About 300 million years ago, “compressional tectonics” occurred again when the Iapetus Ocean between today’s Africa and North America slammed shut, forming the megacontinent Pangea. That collision, the Alleghanian orogeny, pushed up the Appalachians. And, Raymond points out, the massive heat and pressure of the collision changed the sedimentary rock layers of the Grandfather Mountain Basin. Metamorphism turned conglomerate into metaconglomerate, sandstone became metasandstone, and shale morphed into phyllite—all rocks still seen on the mountain. Another major geological event occurred during this collision of continents. The rock that would become Grandfather was covered up when the older rock of the Linville Falls thrust sheet was forced up and over the underlying rock. “That faulting process damaged the older rock, making it more susceptible to erosion,” explains Love. All across the Grandfather Mountain window, from Linville Falls and Linville Gorge to Grandfather’s rocky crest, the older, fragmented overlying layer eroded away. Gradually, the rugged, younger rock below protruded through the opening. Where Grandfather’s summits rise today, a window to another time is thrown open wide. “Grandfather rock” eroded too, but those rocks also evolved, becoming intruded with other kinds of rock, some crystalizing into the erosion-resistant quartz so often seen on the mountain today. “A big part of the mountain’s distinctive shape and ruggedness,” Love maintains, “is the strength of the materials that are exposed.” Quartz is visible all over the mountain as veins in other rock or crystal boulders, especially on the White Rock Ridge, where quartz was once mined. “The durability of quartzite accounts for the towering height of the mountain,” asserts the Blue Ridge Parkway’s 1997 official history of the Grandfather section of the road. It’s the strength of the crags formed in that distant time that give such a striking appearance to the mountain today. The Grandfather Mountain window also provides a view into human history. Before designation of the first Southern Appalachian national parks—Shenandoah and Great Smoky Mountains—early national park proponents envisioned combining Grandfather Mountain and Linville Gorge as one park. Proximity recommended pairing the two, but a deeper kinship was revealed when the Grandfather Mountain window opened so long ago.

Grandfather Mountain’s Backside

You’re likely to overhear people talking about Grandfather’s “backside.” Not his posterior, but the mountain’s “back side” versus the “front side.” Ironically, few talk about the “front side” except by referencing the “back side.” So which is which? That depends. From octogenarian Howard Byrd’s side of the mountain in Foscoe, boyhood trips led “all along the back side, along US 221.” Siblings Richard Chastain and Dixie Chastain Lemons grew up on the Blowing Rock side and they see it differently. “This is the front side we look at here,” Richard maintains. Dixie agrees. “We have the correct view, with the outline of the man laying down. The back side is on NC 105.”

In The Carolina Mountains, Margaret Morley concurs with the Chastains, describing a walk in Foscoe as “the back of the Grandfather,” where “we see the profile from which the mountain is said to have received its name.” If Morley thinks the “back side” profile is the “correct” one, is the Chastains’ Blowing Rock face the wrong one? That, too, depends. Some think the “man laying down” from Blowing Rock is the best profile, and since many people first see the mountain from there, the “outline of the man laying down” must be the “front side,” right? But wait. That “man laying down” from Blowing Rock looks the same from Banner Elk, so how can one face be front or back, right or wrong, especially if the true namesake “Old Man” overlooks Foscoe? Grandfather is silent on these vexing questions. It just may be that Grandfather’s front side or back side is determined by which side you live on or like best. Either that or there are a lot of people who can’t tell Grandfather’s face from his backside.

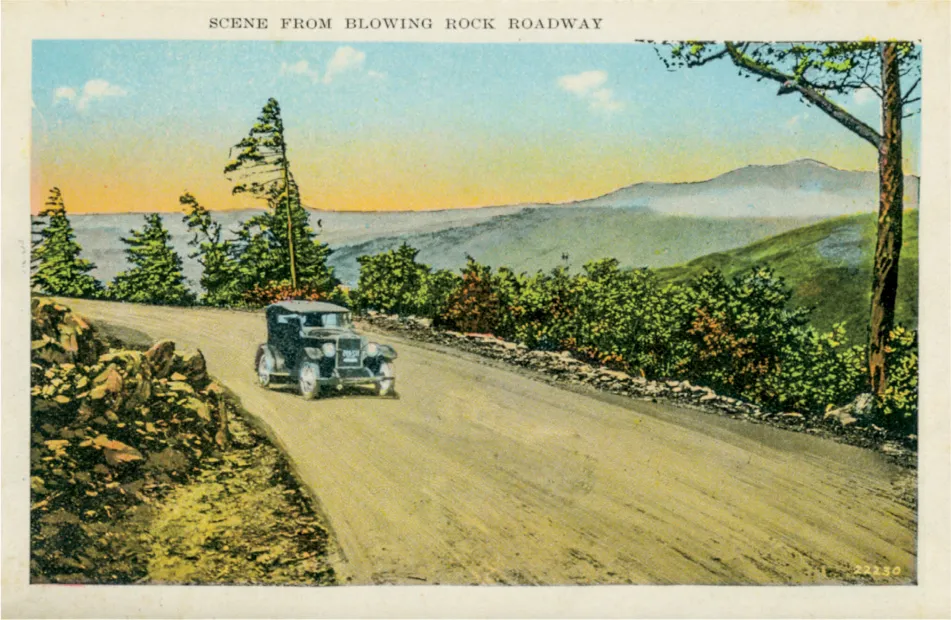

Blowing Rock’s “front side” view of Grandfather is a postcard-perfect vista seen since visitors first made their way to this tempting tourism town in the late 1800s. The town’s namesake viewpoint, The Blowing Rock, and the venerable Green Park Inn were early destinations, and still are. Shirley Stipp Ephemera Collection, D. H. Ramsey Library Special Collections, UNC Asheville 28804.

More Than a Pretty Face

Though decidedly his own man, Grandfather compares in size to other great Appalachian summits such as Mount Washington and Mount LeConte. Peaks connected to Mount Washington and Mount Mitchell complicate an apples-to-apples comparison with Grandfather, a monolith one 1950s newspaper wrote was distinguished by “its aloneness.” Nevertheless, the bulk of all these mountains would fit into an imaginary 7-by-7-mile square drawn from adjacent gaps, notches, and lowlands. Grandfather’s 50 square miles encompass more than just the crest we see above the Blue Ridge Parkway. Grandfather sprawls from the entrance to the Grandfather Mountain attraction on US 221 in the south, north to Holloway Mountain Road in the Blue Ridge Parkway’s Julian Price Park. West to east, it runs from west of NC 105 across the main ridge and far down into Pisgah National Forest, its true base. Thanks to Grandfather’s underlying geology, its many faces gaze out over a vast panorama. In The Carolina Mountains, Margaret Morley (1858–1923) says Grandfather impresses with its “splendid sweep directly up from the abysmal depths of the foothills with no intervening terraces. It has the effect of standing alone, its feet in the far-down valleys, its head in the clouds.” The directness and size of that vertical rise distinguish Grandfather’s jagged dominance over surrounding real estate. Elsewhere in the Southern Appalachians, adjacent plateaus and peaks soften the impact of elevation.

In The Appalachians, Maurice Brooks casts that consideration in stark relief, writing, “A mountain is impressive in proportion to its rise above the base.” The essence of Brooks’s point is that when a summit stands 4,000 or 5,000 feet above adjacent valleys, the immediate visual impact of elevation makes it obvious “this is a major peak.” Take the Smokies’ Mount LeConte, for example. From 6,593 feet, LeConte plummets to Gatlinburg at about 1,400 feet, just more than 5,000 feet. That’s impressive by Appalachian standards, but more than that, Brooks notes, it’s “comparable, so far as rise is concerned to standing in Estes Park and looking toward the Rockies’ Front Range.” That analysis yields a remarkably unappreciated accolade for Appalachia: The East’s highest summits boast a Rocky Mountain–like elevation change. Grandfather is a member of that elite club, rising 4,800 feet above its base. LeConte’s 5,200 feet of vertical drop and Mount Washington’s maximum of nearly 5,500 feet exceed Grandfather’s rise (due largely to their added height above Grandfather’s 5,946 feet). Nevertheless, Grandfather’s relief is among the greatest in the East, equaling Mount Washington’s dramatic lift above New Hampshire valley towns like Jefferson or Berlin (pronounced BER-lin). Grandfather’s perch atop the Blue Ridge gives it the airy sense of altitude found atop Mount Katahdin in Maine, another premier massif that stands largely alone above lake-dotted lowlands. That northernmost anchor of the Appalachian Trail drops about 4,700 feet in 5 miles.

Hugh Morton owned the most rugged mountain in the South; but he wanted more, and the “Fantascope” camera gave it to him. If anything it made the Profile ridge even more facelike. Linville Peak and the Swinging Bridge looked like something out of Switzerland. North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina Library at Chapel Hill. Photos by Hugh Morton.

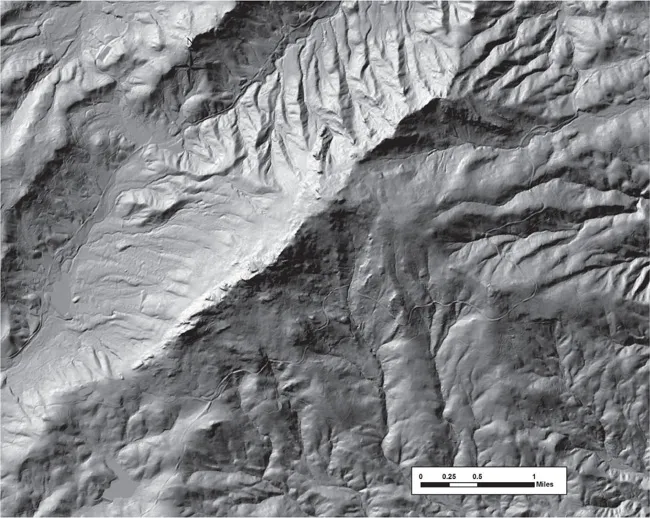

A LiDAR map, named for Light Detecting And Ranging, of the mountain nicely reflects the rugged topography even without topographic lines. This map tracks the mountain’s descent far down its eastern slope. N.C. Geological Survey.

Pardon my partisanship, but I’d argue that the unobstructed plummet from Grandfather’s rock-capped crest equals the impact of peaks with even greater vertical relief. Margaret Morley appreciates that when she describes the distinct edge of the Piedmont as a “shoreless sea of the lowlands.” That oceanlike expanse of flatland North Carolina still impresses today. Other writers have used oceanic imagery in praise of the view. Wilbur G. Zeigler and Ben S. Grosscup’s 1883 book The Heart of the Alleghenies compares the lowest foothills to “a stormy ocean stilled.” With “cumuli building on the horizon you fancy hearing the sound of breakers.” Zeigler loved grappling with big horizons. His 1895 It Was Marlowe first proposed that Christopher Marlowe wrote Shakespeare’s plays. The impression of overviewing an ocean is most striking when inspiring, oft-seen undercast spreads below Grandfather. Morley describes the scene as “all the world blotted out, excepting the Grandfather’s summit rising out of the white mists, so firm to the eye that one is tempted to step out on it.” The mountain’s frequent sea of cloud stretches from the grea...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Sidebars

- Introduction

- Part I: A History of the Mountain

- Part II: A Practical Guide to Hiking and Photography

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgments

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Grandfather Mountain by Randy Johnson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Travel. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.