eBook - ePub

The Won Cause

Black and White Comradeship in the Grand Army of the Republic

- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In the years after the Civil War, black and white Union soldiers who survived the horrific struggle joined the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) — the Union army’s largest veterans' organization. In this thoroughly researched and groundbreaking study, Barbara Gannon chronicles black and white veterans' efforts to create and sustain the nation’s first interracial organization.

According to the conventional view, the freedoms and interests of African American veterans were not defended by white Union veterans after the war, despite the shared tradition of sacrifice among both black and white soldiers. In The Won Cause, however, Gannon challenges this scholarship, arguing that although black veterans still suffered under the contemporary racial mores, the GAR honored its black members in many instances and ascribed them a greater equality than previous studies have shown. Using evidence of integrated posts and veterans' thoughts on their comradeship and the cause, Gannon reveals that white veterans embraced black veterans because their membership in the GAR demonstrated that their wartime suffering created a transcendent bond — comradeship — that overcame even the most pernicious social barrier — race-based separation. By upholding a more inclusive memory of a war fought for liberty as well as union, the GAR’s “Won Cause” challenged the Lost Cause version of Civil War memory.

According to the conventional view, the freedoms and interests of African American veterans were not defended by white Union veterans after the war, despite the shared tradition of sacrifice among both black and white soldiers. In The Won Cause, however, Gannon challenges this scholarship, arguing that although black veterans still suffered under the contemporary racial mores, the GAR honored its black members in many instances and ascribed them a greater equality than previous studies have shown. Using evidence of integrated posts and veterans' thoughts on their comradeship and the cause, Gannon reveals that white veterans embraced black veterans because their membership in the GAR demonstrated that their wartime suffering created a transcendent bond — comradeship — that overcame even the most pernicious social barrier — race-based separation. By upholding a more inclusive memory of a war fought for liberty as well as union, the GAR’s “Won Cause” challenged the Lost Cause version of Civil War memory.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Won Cause by Barbara A. Gannon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

The World African Americans Made in

the Grand Army of the Republic

1

The Only Association Where Black Men and

White Men Mingle on a Foot of Equality

Comrade Jacob Hector, “a tall, fine-looking man, black as coal,” was a popular speaker at Pennsylvania GAR gatherings. A Methodist minister from York, Hector described to his fellow Pennsylvanians the wartime service of black veterans at a state meeting in 1884. “He was here to remind his hearers that they had homes, churches and schools to fight for, while the dark-skinned people of his own race had neither flag nor country and a very poor home, nevertheless they went shoulder to shoulder with the white man” to war. According to Hector, comrades in war remained comrades in peace: “I greet you and you greet me as comrades of the Grand Army of the Republic—the only association this side of Heaven, where black men and white men mingle on a foot of equality.” Similarly, Rev. William Butler, a Memorial Day speaker addressing an all-black GAR post in West Chester, Pennsylvania, understood the unique nature of the interracial GAR. African Americans, he explained, were “thankful for the G.A.R. as an organization, originating with the white man, which cannot shut its doors against the colored man. The Masons did that, the Oddfellows did that and the Knights of Pythias have done the same.” The GAR was the only group that allowed Americans that were “as dark as coal” to stand on a foot of equality with their fellows.1

The GAR was an interracial social organization because its members, both black and white, thought it should be. Since black and white soldiers had served together in the Civil War, African American veterans joined this organization, and they were able to do so because most white veterans believed that their organization should include these men. African Americans participated in the political life of the organization at the state level. They spoke at annual meetings about matters profound and mundane and held elective office. No explanation is needed for why white veterans, who came of age in a society that accepted race-based slavery, sometimes rejected black veterans. This study, therefore, examines why most white veterans accepted black soldiers as their political equals, a status that no other organization granted black Americans in this era.

The story of African Americans in the GAR began before the guns fell silent after Appomattox. Ironically, few Americans at the beginning of the war believed the United States would ever recruit black soldiers, so most Americans would have rejected the notion that African Americans would belong to an interracial veterans' group after the war. Most white northerners believed that African Americans had no place in a war fought to preserve the Union—slavery and all—and therefore the U.S. Army initially refused to recruit black soldiers. Some officers, such as David Hunter in South Carolina, armed slaves under laws written to facilitate the recruitment of laborers; officers who needed soldiers, particularly those opposed to slavery, refused to recognize a color line that excluded black troops. Ultimately, the Emancipation Proclamation allowed the U.S. Army to recruit and officially organize black regiments.2

It is no coincidence that Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation after the battle of Antietam. Not only did he need a victory to announce his intention to free the slaves in rebellious states, but the battle made it clear to northerners that freeing and arming slaves was necessary. In one day, at Antietam Creek, Maryland, 24,000 northern and southern soldiers died or were wounded or missing. The only way modern Americans can appreciate this statistic is to extrapolate these figures based on the current population of the United States. If any battle incurred similar losses today, the United States would suffer more than 240,000 dead, wounded, or missing in a twenty-four-hour period. Antietam may have been the bloodiest single day in the war, but many other battles had equally appalling butchers' bills; the Gettysburg casualty list included more than 50,000 dead, missing, and wounded at the end of the three-day battle. Many northerners opposed slavery on principle, but most supported emancipation because the North needed more soldiers on the front line and fewer slaves behind the lines supporting the war; freeing slaves achieved both ends. Ultimately, 180,000 African Americans served in the Union army and approximately 18,000 served in the Union navy. During the war, the government recruited black soldiers and sailors because of the horrific nature of Civil War combat; in its aftermath, the cruel legacy of this struggle defined the comradeship of black and white veterans in the GAR.3

While both black and white soldiers and sailors served and died, they were not treated equally. African American soldiers served in predominantly black army units, under the command of white officers, and only a handful of African Americans received commissions. For much of the war, black soldiers earned less than their white counterparts; the government equalized pay only after black soldiers and their white officers protested this injustice. Moreover, many African American army units served in support roles, either guarding supply lines or performing manual labor. Given the racial attitudes of that era, it is not surprising that black soldiers were generally seen as inferior to white Americans, unworthy of an officer's rank, deserving less pay, and of questionable fighting value.4

African Americans who served in the Union navy were assigned to integrated ships. Ironically, because black Americans sailed and fought alongside white Americans, they are less visible in the GAR and Civil War Memory. Because the GAR did not officially label either individuals or posts as “Colored,” I relied on the GAR's recording an individual's wartime service to determine a member's race. For example, a death record that lists John Smith, former private, Fifth United States Colored Troops (USCT), obviously refers to an African American member, but the race of John Smith of the USSVermont cannot be determined. Fortunately, I was able to identify the race some of these sailors—such as James Wolff and John Bond of Massachusetts—and tell their story. Overall, the black and white sailors who served together at great hazard seem to have been forgotten, and it is their land-based comrades who have received the most attention. Even black Americans who struggled to remind Americans of black wartime service emphasized black soldiers at the expense of black sailors. Perhaps the heroism of African American sailors on an integrated ship received less attention because it reflected individual sailors' character and not, as would be the case with an all-black unit, the martial virtues of the race.5

When Joseph T. Wilson, a black official of the Virginia GAR and a former sailor who had served in the navy and in one of the earliest black regiments officially recruited into U.S. service in Louisiana, wrote the story of his African American comrades, he emphasized their land campaigns. He described the first major test of African American troops—the 1863 assault at Port Hudson, a critical bastion that guarded an important section of the Mississippi River. According to Wilson, the assault, which included both black and white regiments, had little chance of success. “Never was fighting more heroic than that of the federal army and especially that of the [black] Phalanx regiments,” he wrote. “If valor could have triumphed over such odds, the assaulting force would have carried the works, but only abject cowardice or pitiable imbecility could have lost such a position.” Despite the failure of this attack, Wilson argued, “the battle was lost to all except black soldiers; they, with their terrible loss, had won and conquered a much greater and stronger battery than that upon the bluff. Nature seems to have selected the place and appointed the time for the Negro to prove his manhood.” Service in black regiments allowed these men to demonstrate the manly qualities of their race in a way that service on integrated ships did not.6

Understanding the place of black veterans, both soldiers and sailors, in the interracial GAR requires a brief review of the black military experience in the Civil War. The second major engagement involving black soldiers, the attack on Fort Wagner, South Carolina, by the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Infantry is better known today than Port Hudson because of the movie Glory. George Washington Williams, a pioneering African American historian who rose to the position of adjutant general of the Ohio GAR, chronicled the attack on this “strongly mounted and thoroughly garrisoned earthworks,” observing that such a desperate charge was worthwhile because “the reduction of this fortress . . . [would allow] siege guns [to] be brought within one mile of Fort Sumter, and the city of Charleston, the heart of the rebellion[,] would be within extreme shelling distance.” “From a purely military standpoint,” Williams continued, “the assault upon Fort Wagner was a failure, but it furnished the severest test of Negro valor and soldiership. It was a mournful satisfaction to the advocates of Negro soldiers to point the doubting, sneering, stay-at-home Negro-haters to the murderous trenches of Wagner.” As discussed in later chapters, Wilson and Williams, like their less literary African American compatriots, used their membership in the GAR to challenge those who doubted and scoffed at their service and who tried to erase African American soldiers' service from Civil War Memory.7

The Fifty-fourth Massachusetts and two other all-black units, the Thirty-fifth and the Eighth USCT fought alongside a number of white regiments in a failed expedition to Olustee, Florida. According to Joseph Wilson, who had transferred to the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts and was wounded in this engagement, “The rout was complete; the army was not only defeated but demoralized. The enemy has succeeded in drawing it into a trap for the purpose of annihilating it.” He blamed the failure on the “miserable mismanagement of the advance into the enemy's country. The troops were marched into an [ambush], where they were slaughtered by the enemy at will.” In the end, as Wilson explained, “the battle and the retreat had destroyed every vestige of distinction based upon color. The troops during the battle had fought together, as during the stampede they had endured its horrors together.” How the horror of war destroyed, or at least damaged, distinctions based on color is an essential element in understanding the interracial GAR.8

While the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts, a state regiment, has received the lion's share of what glory has been allowed to black units, most black soldiers served in units organized by the federal government—the U.S. Colored Troops, such as the Eighth and the Thirty-fifth. In addition to the Fifty-fourth, Massachusetts organized two other African American units that kept their identity as state regiments throughout the war, the Fifty-fifth Massachusetts Infantry and the Fifth Massachusetts Cavalry. Only one other state, Connecticut, formed black regiments that did not transfer to federal authority, and only one of these units, the Twenty-ninth Connecticut, saw any action. William Fox's Regimental Losses in the American Civil War, published in 1889, documented the entire spectrum of black military service, which included USCT regiments. According to Fox, “Before the war closed the colored troops embraced 145 regiments of infantry, 7 of cavalry, 12 of heavy artillery, 1 of light artillery, 1 of engineers; [for a] total [of] 166” regiments. Three black regiments, the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts, the Eighth USCT, and the Kansas-based Seventy-ninth USCT, made Fox's list of the elite 300 Fighting Regiments. He listed all of the separate engagements and skirmishes involving black soldiers across the country from Wilmington, North Carolina, to Poison Spring, Arkansas. White GAR members who read Fox's book would have been aware that black Americans' Civil War service encompassed more than one attack by a single Massachusetts regiment that ended in glory. While historians have emphasized segregation in the Civil War, the existence of well over a hundred regiments with the word “Colored” in their name kept alive the story of black service and sacrifice in this struggle.9

Of all the battles of the Civil War, those that relied most heavily on black combat troops involved the final campaigns against Richmond and Petersburg. Williams maintained that “by the spring of 1864 a numerous force of Negro troops had been added to [the] army, and an active and brilliant military career opened up to them.” These campaigns are not as well known today as are the earlier battles in the East, such as those at Antietam and Gettysburg. Neglect of these later campaigns may be due to their grim character. Much of the time, soldiers lived in trenches with only a few pitched battles to break the stalemate, similar to the battles in World War I, with its static warfare and none of the “romance” of the war's earlier battles. Unfortunately, when historians and others slight these campaigns, they reinforce the historical amnesia that wrote black soldiers out of the all-white brothers' war. Just when African American soldiers arrived on the center stage of Civil War history, much of the audience had left the theater.10

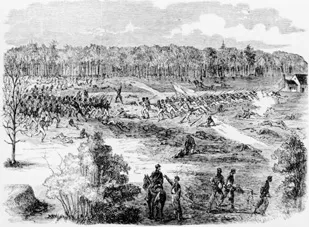

Fox's study would have reminded Americans of black Americans' service in the engagements around Richmond and Petersburg if they consulted Fox's study. An attack by African American soldiers on Petersburg on June 15, 1864, was, according to Fox, “a brilliant success, [which resulted in the capture of] the line of works in its front and seven pieces of artillery.” He maintained that “had the Army of the Potomac arrived in time to follow up the success of the colored troops, Petersburg would have been taken then.” Later in that campaign, a mine exploded underneath the Confederate line and created a large “Crater,” the name given to another battle involving black troops. Fox contended that the black division that had been selected to lead the charge was “sent in last. It was not ordered forward until the assault was a bloody failure, and although it did all that men could do, it was unable to retrieve the disaster.” He cited fifteen black units for their service in the various battles around Petersburg and Richmond, including lesser-known engagements at Chafin's Farm and New Market Heights. Even though black and white soldiers served in segregated units in these crucial final battles, they later shared a common fellowship as members of the GAR.11

The Twenty-second USCT advancing against the Confederate lines at Petersburg. From Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, 1896, in author's collection.

One year after Richmond fell, a handful of battered survivors of the Union army formed the first GAR post in Illinois. While in theory the GAR was born in 1866 and died in 1956, the life of the organization had two distinct phases. During phase one, the first decade of its existence, the GAR flourished, but accusations of partisanship and the institution of an unpopular new ritual that re-created military ranks and hierarchies led to the GAR's decline. Mary R. Dearing, in the first modern study of the GAR, Veterans in Politics, characterized the GAR and its local posts as “efficient cogs in the Republican [political] machine.” Membership dropped so precipitously that in some states the GAR disappeared; by 1876, the organization had about twenty-seven thousand members.12

The GAR was reborn in the 1880s when it remade itself into an organization that emphasized charity, patriotism, and good fellowship among veterans of all political stripes. As Stuart McConnell has argued, “the overt involvement of the order in electoral politics . . . did not long survive Grant's first term. Instead, the GAR after 1872 wore several masks: fraternal lodge, charitable society, special-interest lobby, patriotic group, political club.” Mary Dearing's study documents not so much the GAR as partisan political phenomenon but as the first major political interest group and lobbying organization—similar to its modern counterparts, the AARP (formerly known as American Association for Retired People). She also rightly emphasizes veterans' pensions as its overriding political interest. During the late 1880s, the GAR lobbied hard to ensure that all veterans received a pension based on their wartime service. (Previously, veterans had to prove a service-related disability to get this monthly payment.) The GAR's advocacy of veterans' pensions ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- THE WON CAUSE

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- PART I The World African Americans Made in the Grand Army of the Republic

- PART II The World Black and White Veterans Made Together

- PART III Brothers Ever We Shall Be: Black and White Comradeship in the GAR

- PART IV The Won Cause: A Meaning for Their Suffering

- Epilogue

- Appendix I African American GAR Posts

- Appendix II Integrated GAR Posts

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index