- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

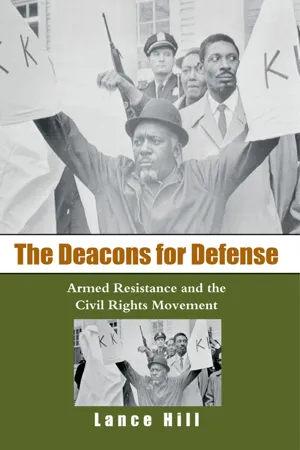

In 1964 a small group of African American men in Jonesboro, Louisiana, defied the nonviolence policy of the mainstream civil rights movement and formed an armed self-defense organization — the Deacons for Defense and Justice — to protect movement workers from vigilante and police violence. With their largest and most famous chapter at the center of a bloody campaign in the Ku Klux Klan stronghold of Bogalusa, Louisiana, the Deacons became a popular symbol of the growing frustration with Martin Luther King Jr.’s nonviolent strategy and a rallying point for a militant working-class movement in the South.

Lance Hill offers the first detailed history of the Deacons for Defense and Justice, who grew to several hundred members and twenty-one chapters in the Deep South and led some of the most successful local campaigns in the civil rights movement. In his analysis of this important yet long-overlooked organization, Hill challenges what he calls “the myth of nonviolence” — the idea that a united civil rights movement achieved its goals through nonviolent direct action led by middle-class and religious leaders. In contrast, Hill constructs a compelling historical narrative of a working-class armed self-defense movement that defied the entrenched nonviolent leadership and played a crucial role in compelling the federal government to neutralize the Klan and uphold civil rights and liberties.

Lance Hill offers the first detailed history of the Deacons for Defense and Justice, who grew to several hundred members and twenty-one chapters in the Deep South and led some of the most successful local campaigns in the civil rights movement. In his analysis of this important yet long-overlooked organization, Hill challenges what he calls “the myth of nonviolence” — the idea that a united civil rights movement achieved its goals through nonviolent direct action led by middle-class and religious leaders. In contrast, Hill constructs a compelling historical narrative of a working-class armed self-defense movement that defied the entrenched nonviolent leadership and played a crucial role in compelling the federal government to neutralize the Klan and uphold civil rights and liberties.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Deacons for Defense by Lance Hill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Política y relaciones internacionales & Historia de Norteamérica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1 Beginnings

EARNEST THOMAS HAD been a fighter all his life. Born in Jonesboro, Louisiana, on 20 November 1935, Thomas was descended from a long line of independent tradesmen and farmers. He came of age in the Deep South under the system of segregation, yet he knew white people as well as his own folk. Racial segregation fought a relentless battle against human nature—against the instinctual longing for companionship and shared joy among members of the human race. The intimacy of everyday life tempted people to disregard the awkward rituals of segregation. In his youth Thomas had frequented the local swimming hole in Jonesboro, a gentle creek that wound its way through the pines. Its tranquil waters welcomed children of all colors. Here black and white children innocently played together, splashing and dunking. At a distance, colors disappeared into a shadow silhouette of bobbing heads, the languid summer air disturbed only by occasional shrieks of joy.1

Yet inevitably nature surrendered to the mean habits of adult society. Thomas recalled that sometimes the whites would band together and swoop down on a handful of frolicking blacks, claiming the waters as the spoils of war. On other occasions, Thomas would join a charging army of whooping black warriors as they descended on the stream, scattering a gaggle of unsuspecting white boys. The swimming hole wars of his youth provided Earnest Thomas with one enduring lesson: rights were secured by force more often than by appeals to reason and moral argument.

In the summer of 1964 Thomas was swept up in a new phase of the civil rights movement and became a leader of the founding chapter of the Deacons for Defense and Justice. How the most widely known armed self-defense organization in the Deep South came into existence in a remote Louisiana town, far removed from the movement centers and media limelight, in itself speaks volumes about a largely invisible conflict within the civil rights movement between the partisans of nonviolence that descended on the South and an emerging working-class movement that resisted pacifism in the face of police and vigilante terror.

In the nineteenth century the pine hills of North Louisiana were a hostile refuge for the poor and dispossessed. Following the Civil War, legions of starving and desperate whites were driven into the pine hills by destruction, drought, and depleted soil in the Southeast. They arrived to find the best alluvial land controlled by large landowners and speculators. The remaining soil was poorly suited for farming, rendered haggard and sallow by millennia of acidic pine needles deposited on the forest floor. The lean migrants scratched the worthless sandy soil, shook their heads, and resigned themselves to the unhappy fate of subsistence farming.

Upcountry whites eked out a living with a dozen acres of “corn and ’taters,” a few hogs for fatback, trapping and hunting for game, and occasionally logging for local markets. Not until the turn of the century, when the large-scale lumber industry invaded the pines, did their hopes and prospects change. Even then, prosperity was fleeting. By the 1930s the lumber leviathans had stripped the pine woods bare, leaving a residue of a few paper and lumber mills. Those fortunate enough to find work in the pulp and paper industry watched helplessly in the 1950s and 1960s as even these remaining jobs were threatened by shrinking reserves and automation.2

These Protestant descendants of the British Isles were the latest in several generations of whites forced west by a slave-based economy that rapidly expended the very soil it arose from. With the end of the Civil War their plight was compounded by more than three million black freedmen surging across the South in search of work and land. Emancipation thrust blacks into merciless competition with whites for the dearth of work, land, and credit.

The freedmen also looked to the pines for deliverance. Blacks who remained on plantations lived in constant fear of new forms of bondage such as gang labor and sharecropping. Thousands of dusty, tattered black families packed their belongings and trekked into the hills to escape the indignities of debt peonage. Like their white competitors, the freedmen sought the dignity and independence conferred by a few acres of land and the freedom to sell their labor.

The pine hills were soon peopled by the most independent and self-sufficient African Americans: those willing to risk everything to escape economic bondage. Their passionate independence flourished in the hills as they worked as self-employed timber cutters and log haulers. By the middle of the twentieth century many of their descendants had left the land, drawn to the small industrial towns that offered decent wages in lumber and paper mills.

From the end of the Civil War through the 1960s these two fiercely independent communities, black and white, traveled separate yet parallel paths in the pine hills of North Louisiana. In the summer of 1964, in the small town of Jonesboro, these two worlds would finally cross paths—as well as swords.

Jonesboro was one of dozens of makeshift mill towns that sprang up as eastern businesses rushed to mine the vast timber spreads of Louisiana. Incorporated in 1903, the town was little more than an appendage to a sawmill—crude shacks storing the human machinery of industry.

By the 1960s Jonesboro lived in the shadow of the enormous Continental Can Company paper mill located in Hodge, a small town on the outskirts of Jonesboro. The New York–based company produced container board and kraft paper at the Hodge facility and employed more than 1,500 whites and 200 blacks. In addition, many blacks found employment at the Olin Mathieson Chemical Company. Those blacks who were not fortunate enough to find work in the paper mill labored as destitute woodcutters and log haulers on the immense timber landholdings owned by Continental Can.3

Almost one-third of Jonesboro's 3,848 residents were black. Though by southern standards Jonesboro's black community was prosperous, poverty and ignorance were still rampant. Nearly eight out of every ten black families lived in poverty. Ninety-seven percent of blacks over the age of twenty-five had never completed a high school education. The “black quarters” in Jonesboro and Hodge consisted of dilapidated clapboard shacks, with cracks in the walls that whistled in the bitter winter wind. Human waste ran into the dirt streets for want of a sewerage system. Unpaved streets with exotic names like “Congo” and “Tarbottom” served alternately as dust storms and impassable rivers of mud.4

Daily life in Jonesboro painstakingly followed the rituals and conventions of Jim Crow segregation. A white person walking downtown could expect blacks to obsequiously avert their eyes and step off the sidewalk in deference. Jobs were strictly segregated, with blacks allotted positions no higher than “broom and mop” occupations. The local hospital had an all-white staff, and the paper mill segregated both jobs and toilets. Blacks were even denied the simple right to walk into the public library.5

On the surface there appeared to be few diversions from the tedium and poverty. The ramshackle “Minute Spot” tavern served as the only legal drinking establishment for blacks. To Danny Mitchell, a black student organizer who arrived in Jonesboro in 1964, Jonesboro's African Americans appeared to take refuge in gambling and other unseemly pastimes. Mitchell, with a note of youthful piety, once reported to his superiors in New York that most of Jonesboro's black community “seeks enjoyment and relief from the frustrating life they endure through marital, extramarital, and inter-marital relationships.”6

But there was more to Jonesboro than sex and dice. Indeed, segregation had produced a complex labyrinth of social networks and organizations in the black community. The relatively large industrial working class preserved the independent spirit that characterized blacks in the pine woods. As in many other small mill towns, blacks in Jonesboro had created a tightly knit community that revolved around the institutions of church and fraternal orders. In the post–World War II era, black men in the South frequently belonged to several fraternal orders and social clubs, such as the Prince Hall Masons and the Brotherhood for the Protection of Elks. These formal and informal organizations provided a respite from the oppressive white culture. They offered status, nurtured mutual bonds of trust, and served as schools for leadership for Jonesboro's black working and middle classes.7

In the period of increased activism following World War II, most of Jonesboro's civil rights leadership emerged from the small yet significant middle class of educators, self-employed craftsmen, and independent business people (religious leaders were conspicuously absent from the ranks of the reformers). While segregation denied blacks many opportunities, it also created captive markets for some enterprising blacks, particularly in services that whites refused to provide them. There were twenty-one black-owned businesses in Jonesboro in 1964, including taxi companies, gas stations, and a popular skating rink.8

The black Voters League of Jonesboro drew its leadership primarily from the ranks of businessmen and educators, such as W. C. Flannagan, E. N. Francis, J. W. Dade, and Fred Hearn. Flannagan, who led the league in the early 1960s, was a self-employed handyman who also published a small newsletter. Francis owned several businesses, including a funeral home, grocery store, barber shop, and dry-cleaning store. Dade was, by local standards, a man of considerable wealth. He taught mathematics at Jackson High School and supplemented his teaching salary with income from a dozen rental houses. Hearn was also a teacher and worked as a farmer and installed and cleaned water wells.9

Jackson Parish (county), where Jonesboro is located, had had a small but well-organized chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) since the 1940s. In 1956 the Louisiana NAACP was gravely damaged by a state law that required disclosure of membership. Rather than divulge members’ names and expose them to harassment, many chapters replaced the NAACP with “civic and voters leagues.” Such was the case in Jackson Parish, where the NAACP became the “Jackson Parish Progressive Voters League.” From its inception, the Voters League concentrated on voter registration and enjoyed some success. When the White Citizens Council and the Registrar of Voters conspired to purge blacks from the registration rolls in 1956, the Voters League retaliated with a voting rights suit initiated by the Justice Department. The Voters League prevailed and federal courts eventually forced the registrar to cease discriminating against blacks, to report records to the federal judiciary, and to assist black applicants in registering to vote. By 1964 nearly 18 percent of the parish voters were black, a remarkably high percentage for the rural South.10

The Voters League never commanded enough votes to win elective office for a black candidate. For the most part, the league was limited to delivering the black vote to white candidates in exchange for political favors. Although political patronage offered some benefits to the black community at large, it more frequently created opportunities for personal aggrandizement. At its worse, patronage disguised greed as public service. Some Voters League critics felt that its leaders were principally interested in gaining personal favors from politicians, and there was credence to the charge.11

In truth, the white political establishment offered a tempting assortment of patronage rewards to compliant black leaders in an effort to discourage them from conducting disruptive civil rights protests. Inducements included positions in government and public education, ranging from school bus drivers to school administrators. White political patronage bought influence and loyalty in the black community. The practice testified to the fact that white domination rested on more than repression and fear: it depended on consent by a segment of the black middle class. Conflicts over segregation were to be resolved by gentlemen behind closed doors. Time and again, civil rights activists in Louisiana found the black middle class and clergy to be significant obstacles to organizing. One activist in East Felicana Parish reported that the lack of interest in voter registration in 1964 could be attributed to, among other things, the “general fear-inducing activity of the very active community of Toms. Every move we make is broadcast by them to the whole town.”12

Indeed, the “mass meeting” technique represented a rudimentary form of working-class control over the black middle class and redefined the political decision-making process in the black community. Prior to the civil rights movement, racial conflicts and issues were normally negotiated by intermediaries: middle-class power brokers, the NAACP, or the Voters Leagues. During the civil rights movement direct democracy mass meetings assembled the black community to make decisions by consensus, a process that functioned not only to build community support for the leaders’ decisions, but also to prevent middle-class leaders from making secret agreements and compromises with the white power structure. Plebiscitary democracy guaranteed that all agreements had to pass muster with the black rank and file: the working class, the poor, and the youth.13

There were good reasons for the suspicions exhibited by the rank and file. Black leadership was more complex and divided than the undifferentiated, united image reflected in the popular historical myth of the civil rights movement. The movement did not march in unison and speak with one voice. The black community had its share of traitors, rascals, and ordinary fools. In general, though, the leaders of the Voters League in Jonesboro were honorable men who had the community's interests at heart. Nonetheless, it was difficult for the league to generate enthusiasm for voting rights when the ballot benefited only a handful of elite blacks. For most black voters in Jonesboro, elections offered little more than a Hobson's choice between racism and more racism.

Deep divisions existed between the black clergy and the movement in Jonesboro. Only one church, Pleasant Grove Baptist Church, initially supported the movement. Pleasant Grove had a highly active and concerned membership, led by Henry and Ruth Amos who operated a gas station and Percy Lee Bradford, a cab driver and mill worker. The dearth of civil rights church leaders in Jonesboro was no anomaly. In both large cities and small towns in the South, the attitude of black clergy toward the movement generally ranged from indifference to outright hostility. Medgar Evers, the martyred Mississippi NAACP leader, once grumbled that the ministers “won't give us 50 cents for fear of losing face with the white man.” Martin Luther King did not mince words about the complacency of his brothers of the collar in Birmingham: “I'm tired of preachers riding around in big cars, living in fine homes, but not willing to fight their part,” said King. “If you can't stand up with your own people, you are not fit to be a leader.”14

The conservative character of rural black clergy was owing to several factors. Church buildings were vulnerable to arson in retaliation for civil rights activities (black churches in the South were frequently located outside of town in remote, unguarded areas). It was common for insurance companies to cancel insurance on churches that had been active in the movement. Moreover, black ministers depended on good relationships with whites to obtain loans for the all-important brick-and-mortar building projects.

But the clergy's conservatism was also emblematic of the contradictory character of the black church. On the one hand, the church was a force for change. It provided a safe and nurturing sanctuary in a hostile, oppressive world. In the midst of despair, it forged a new community, nourished racial solidarity, defined community values, and provided pride and hope. And when it adopted the twentieth-century “social gospel” theology, as practiced by Martin Luther King, the black church could even be a powerful vehicle for social justice and national redemption.

In contrast to this uplifting role, though, the black church could also lapse into a fatalistic outlook that bred passivity and political cynicism. Fatalism is a rational and effective adaptation in reactionary times when people live on hope alone. Some of the black clergy preached the gospel of resignation—extolling the glories of heaven and eschewing social and political reform—and, worse yet, honored the color line and its attendant traditions of deference. During the Montgomery Bus Boycott, black leader E. D. Nixon gave voice to the frustration that many felt with the black clergy. “Let me tell you gentlemen one thing,” Nixon told a group of ministers he had gathered to organize the boycott. “You ministers have lived off of these wash-women for the last hundred years and ain't never done nothing for them.” Nixon scolded that it was shameful that women were leading the boycott while the ministers were afraid to even have their names published as supporters. “We've worn aprons all our lives. It's time to take the aprons off … if we're gonna be mens, now's the time to be mens.”15

In contrast to the spotty record of the black church in the rural movement, the black fraternal orders were frequently the backbone of...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- The Deacons for Defense

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- CHAPTER 1 Beginnings

- CHAPTER 2 The Deacons Are Born

- CHAPTER 3 In the New York Times

- CHAPTER 4 Not Selma

- CHAPTER 5 On to Bogalusa

- CHAPTER 6 The Bogalusa Chapter

- CHAPTER 7 The Spring Campaign

- CHAPTER 8 With a Single Bullet

- CHAPTER 9 Victory

- CHAPTER 10 Expanding in the Bayou State

- CHAPTER 11 Mississippi Chapters

- CHAPTER 12 Heading North

- CHAPTER 13 Black Power—Last Days

- CONCLUSION The Myth of Nonviolence

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index