eBook - ePub

Building a Housewife's Paradise

Gender, Politics, and American Grocery Stores in the Twentieth Century

- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Building a Housewife's Paradise

Gender, Politics, and American Grocery Stores in the Twentieth Century

About this book

Supermarkets are a mundane feature in the landscape, but as Tracey Deutsch reveals, they represent a major transformation in the ways that Americans feed themselves. In her examination of the history of food distribution in the United States, Deutsch demonstrates the important roles that gender, business, class, and the state played in the evolution of American grocery stores.

Deutsch’s analysis reframes shopping as labor and embeds consumption in the structures of capitalism. The supermarket, that icon of postwar American life, emerged not from straightforward consumer demand for low prices, Deutsch argues, but through government regulations, women customers' demands, and retailers' concerns with financial success and control of the “shop floor.” From small neighborhood stores to huge corporate chains of supermarkets, Deutsch traces the charged story of the origins of contemporary food distribution, treating topics as varied as everyday food purchases, the sales tax, postwar celebrations and critiques of mass consumption, and 1960s and 1970s urban insurrections. Demonstrating connections between women’s work and the history of capitalism, Deutsch locates the origins of supermarkets in the politics of twentieth-century consumption.

Deutsch’s analysis reframes shopping as labor and embeds consumption in the structures of capitalism. The supermarket, that icon of postwar American life, emerged not from straightforward consumer demand for low prices, Deutsch argues, but through government regulations, women customers' demands, and retailers' concerns with financial success and control of the “shop floor.” From small neighborhood stores to huge corporate chains of supermarkets, Deutsch traces the charged story of the origins of contemporary food distribution, treating topics as varied as everyday food purchases, the sales tax, postwar celebrations and critiques of mass consumption, and 1960s and 1970s urban insurrections. Demonstrating connections between women’s work and the history of capitalism, Deutsch locates the origins of supermarkets in the politics of twentieth-century consumption.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Building a Housewife's Paradise by Tracey Deutsch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Retail Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Women and the Social Politics of Food Procurement

For much of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth, urban Americans bought food from peddlers, public markets, and local grocers, and picked produce from their own gardens. They bartered, negotiated, demanded personal attention, and submitted themselves to the canny gaze of food sellers—when they were not scavenging or stealing. Too important to be done thoughtlessly or according to anyone else’s standards, food shopping in its everyday enactments was a complicated pursuit, which made it difficult to think of women as a unified group or of food selling as a peaceful procedure.

This chapter argues that urban food shopping in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was—and was understood to be—difficult, timeconsuming, and important work. The narrative uncovers the central components of that work, focusing on the gendered division of labor that assigned food shopping to women, the weighty social and cultural role of food, the geographic density of food retailers, the diversity of retail formats, and the legacy of personal assertiveness that surrounded food marketing in this period.

The social context of food shopping helps explain why it was such difficult work and why women took it so seriously. Following Marjorie DeVault’s conclusion that the difficult labor of food preparation is part of a larger “care-giving” project for which women are primarily responsible, I embed food procurement in broader ideological and social contexts.1 The chapter investigates particularly the gender norms, communal ties, religious identities, and familial loyalties that were at stake in food work during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In endless negotiations over the price and quality of goods, grocers and customers scrutinized each other’s personalities and habits, as well as racial and ethnic loyalties. Small independent grocery stores, market stalls, and peddlers’ wagons—although often romanticized in our own time—were places of discord and debate as well as friendship and community.2

The chapter also reveals the structural implications of these social politics, demonstrating that the commercial spaces in which food was sold were shaped by grocers’ expectations that women customers would demand significant authority over the terms of purchase. Personalized interactions and attention seemed both problematic and inevitable to most retailers.

Ultimately, the social tensions that permeated stores and women’s food shopping motivated grocers to move toward the top-down, standardized aesthetics of supermarkets and mass retailing. Thus, the way in which women shopped had enormous implications for political economy and the workings of capitalist exchange over time. The world of personal transactions described in this chapter stands in contrast to and helps explain the origins of the streamlined world of supermarkets and mass retail described later in the book.

Shopping and Social Relationships

At the heart of shopping for food was the effort to win individual attention. Indeed, this remained a constant refrain of Chicagoans for nearly forty years. A personalized interaction, steeped in mutual skepticism and canniness, required work on the part of sellers as well as buyers. “Marketing,” noted one observer in 1911, “is still a question of beating down the tradesman from an outrageous price to a reasonable one.”3 One letter writer in 1913 urged her comrades to avoid shopping in the afternoon, when clerks were too busy to pay attention to individuals. In the mornings, she observed, “you have the pick of the market . . . instead of stale leftovers.”4 Sometimes, this expectation of individual attention resulted in requests that required remarkable levels of trust and personalized service from sellers. Marion Harland advised readers of her housekeeping column in the Chicago Tribune to have “a little forethought” and ask butchers to save cheaper cuts of meat until they could come in and purchase them.5

Women might ask for these services, but there was no guarantee that retailers would comply or that they would do so readily. Not surprisingly, when Chicagoans talked about stores, it was often to complain about their shortcomings: “As every housekeeper knows,” wrote a Chicago journalist in August 1896, “one of the most exacting demands of housekeeping is marketing.” The author went on to decry the options available to women. Placing orders with stores, either via delivery boys or over the telephone, could lead to subpar foods arriving at one’s doorstep. If one “sallied forth” oneself, the well-meaning housewife found “the task of spending money scarcely less laborious than the task of earning it.” Such a job required a shopper to be able to leave home just after breakfast or risk limited selection and long lines later in the day. “Then,” she continued, “there is the friction of discussing the demerit of items previously delivered . . . and the often fruitless effort to secure just what is desired.” Even women who had time for this face-to-face bargaining found it “weariness to the flesh.”6

Shoppers’ frustrations speak to the institutional effects of this mode of shopping and to the difficult business of distributing food. The inescapable individualism of shoppers was credited with causing spectacular bottlenecks all along the distribution chain. One anonymous observer of grocery stores pointed out that efforts to guess at what women wanted and therefore to standardize and minimize service would surely end in failure: “About the only thing upon which housewives are agreed,” they lamented, “is that prices are too high.”7

Similarly, the authors of a 1926 study on Chicago’s South Water Market explained the difficulty of streamlining produce distribution as an inevitable result of selling to individual women. Quoting from a contemporaneous study of markets in New York, the authors asserted: “Partly because she cannot find the room to store perishables in a city apartment and partly because she prefers to see what is new at the vegetable market each day, the modern housekeeper pursues a hand-to-mouth purchasing policy . . . . The consumer wants a head of lettuce or a half-dozen oranges today and a grapefruit and two ounces of mushrooms tomorrow. The retail grocer or vegetable man tries to carry a little bit of everything and consequently not much of any one variety.” The result, they concluded, was enormous congestion at produce markets as large lots were broken into very small quantities.8 A frustrated housewife summed up her own perspective on the matter succinctly: “Individuality is greatly discouraged by those who serve her,” she noted, “as they deem it an inroad on the even tenor of their way.”9 The need to serve women as individuals was both fundamental to and a problem for the operation of grocery stores.

As these accounts of shopping attest, food buying in the first decades of the twentieth century was an intensely, indeed uncomfortably, social encounter. The exchange was neither abstract nor impersonal, but took place through relentlessly messy social relations. Indeed, these social relations made exchange possible and, in the minds of retailers, they were an inevitable part of doing business.10 Understanding how these relations mattered to stores themselves requires exploring food shopping in the lives and work of women who so often undertook this task. To appreciate the social relations in stores, one must appreciate what food buying meant outside stores.

Shopping in the Context of Housekeeping

Food shopping was difficult, in large measure, because it had to be accomplished around so much other work. Evidence from early Anglo America describes women’s responsibility for most tasks associated with home life. In the antebellum United States, in the words of Jeanne Boydston, “housework remained the personal responsibility and defining labor of women.”11 Although the particular tasks, standards, and technologies changed over time, “women’s work” conjured up images of cooking, cleaning, and caretaking through the later nineteenth and twentieth centuries.12 Even amid the astonishing changes in women’s tasks during the extension of industrial production and market relations in the early nineteenth century, women continued to answer for the cleanliness of their homes and continued to oversee the procurement of needed items, to process the raw materials of food and cloth into meals and clothing, and to perform the bulk of the child care in their households. Things had not changed by the end of the century: “There is the whole house to put in order and keep in order,” wrote the pseudonymous “Aunt Hannah” in 1897, “the marketing, etc., sewing for the whole family, mending and darning and necessary attention to the laundrying. The children must be kept clean and clothed, fed and nursed through all of those dread forty children’s diseases and brought up in the way they should go.” “The life of a housewife,” she concluded, “is an extremely busy one.”13

What we know of household technology and housework shores up Aunt Hannah’s claim. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, women did perform and oversee an enormous number of tasks. Some took up whole days (washing, for instance), but most were intermittent. Into this category went meal preparation, sweeping and mopping, and tending fires and lamps. The poorer the household, the more difficult daily maintenance could be. Crowded tenements were more difficult to keep clean than were less densely populated middle-class homes. Food was more difficult to come by for the poor than for the better off. And in working-class neighborhoods, water was more likely to require long hauling than to be available in backyard pumps or indoor taps.14

Finally, ideological pressures and tensions contributed to the difficulty, rewards, and significance of housework generally and of food shopping specifically.

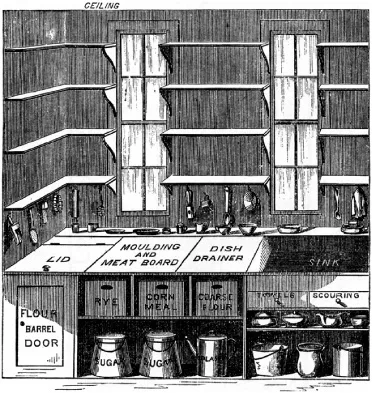

FIGURE 1.1. Catharine Beecher’s kitchen. Catharine Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe, plan of sink and cooking form, 1869. (Catharine Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe.The American Woman’s Home. 1869. (Reprint, Hartford: Stowe-Day Foundation, 1975.)

Food, and its preparation and serving, figured prominently in the ideology of domesticity and its classed nature.15 Beginning at least in the ante-bellum period with the publication of women’s housekeeping guides, cooking and serving were celebrated as the stage on which women could best enact the work of efficiency and of generosity—work that would maintain familial coherence. Meals were the vehicle for love, nutrition, the reinforcement of religious and communal norms, the education of children, and displays of skill— for all the ways that women might convey their affection, nurturance, and fitness.16 Prescriptions for cooking and eating changed over time but nearly always posited meals as central moments in families’ lives. Catharine Beecher’s famous sketch of the ideal kitchen points both to the work of cooking and to its importance in the vision of middle-class domesticity. Later iterations of the ideology of domesticity continued to place enormous emphasis on women’s work around food. By the turn of the twentieth century, the emerging “science” of home economics encouraged women to see food and its preparation as a framework for their performance of efficiency and careful attention to family’s health. (This emphasis on mealtime has not ended; in the early twenty-first century, researchers suggested that home-cooked family dinners would prevent everything from premarital sex to obesity to drug use.)17 The ideology of domesticity emphasized the “work” done by meals and firmly assigned responsibility for those meals to women.

Over time, food purchasing became a marker of gender normativity for women. Even novelists reflected this broad discourse, which regarded failure to shop as failure to perform one’s duties as a wife and mother. In Sister Carrie, Theodore Dreiser uses the male protagonist Hurstwood’s assumption of food shopping as a mark of his declining fortunes and the dissolution of his and Carrie’s relationship.18 This ideological context made women’s food procurement a social and cultural necessity as well as a physical one.

Commerce, Food, and Shopping as Women’s Work

For all of the celebration of cooking as a bulwark against the dangers and exhaustions of work, and therefore as a duty particularly appropriate for women, the ingredients that cooks used and the technology with which those ingredients were prepared often required enormous physical labor. Experts at the turn of the century estimated that the work of tending stoves for a little under a week could easily require the cook to lift 292 pounds of coal.19 Nor were tasks such as preserving fruit, baking bread, or plucking chickens for the faint of heart. For these reasons, servants sometimes did much of the work of cooking in middle-class homes, although this practice was less common by the early decades of the twentieth century. Even in families that employed a maid or cook, the employer was supposed to oversee techniques, meal choices, and ingredients.20 Thus, employing a servant complicated but did not preclude a middle-class woman’s taking credit for feeding her family.

Perhaps the most important contradiction that food-work revealed in the ideology of domesticity was the involvement of commerce and money in housework. By the turn of the twentieth century, food was increasingly obtained through marketplace transactions.21 Food was one of the first commodities encompassed by a burgeoning system of mass distribution, so that by the turn of the century, many women could purchase glassed and canned soups and jellies, preserved vegetables, crackers, cereals, and nationally or regionally branded flour and cornmeal. All these products eased the work of cooking and introduced more variety in the diets of those families who could afford them. Other changes also increased the variety of food purchased. As transportation and refrigerated shipping became more feasible, urban markets also offered an impressive and much-appreciated selection of fresh fruits and vegetables, meat, and dairy.22 According to one estimate, Water Street Market in Chicago, an important distribution point for both local and regional produce, saw fifty-three different varieties of produce move through on an average day.23 While not all families could afford to purchase exotic goods, access to markets allowed many to make occasional forays into more extensive and varied diets—and to lessen some of the work of meal preparation.

There are many reasons why Americans regularly purchased their food. Some reflected sheer practicality: the increasing numbers of Americans who lived in cities encountered enormous difficulty in trying to produce and preserve food in small urban lots. Also, the rudimentary refrigera...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Building a Housewife’s Paradise

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- Figures and Tables

- Introduction

- 1 Women and the Social Politics of Food Procurement

- 2 Small Stores, Big Business

- 3 The Changing Politics of Mass Consumption, 1910–1940

- 4 Moments of Rebellion

- 5 Grocery Stores Trade Up

- 6 Winning the Home Front

- 7 Babes in Consumerland

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgments

- Index