eBook - ePub

The Yankee Plague

Escaped Union Prisoners and the Collapse of the Confederacy

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

During the winter of 1864, more than 3,000 Federal prisoners of war escaped from Confederate prison camps into South Carolina and North Carolina, often with the aid of local slaves. Their flight created, in the words of contemporary observers, a “Yankee plague,” heralding a grim end to the Confederate cause. In this fascinating look at Union soldiers' flight for freedom in the last months of the Civil War, Lorien Foote reveals new connections between the collapse of the Confederate prison system, the large-scale escape of Union soldiers, and the full unraveling of the Confederate States of America. By this point in the war, the Confederacy was reeling from prison overpopulation, a crumbling military, violence from internal enemies, and slavery’s breakdown. The fugitive Federals moving across the countryside in mass numbers, Foote argues, accelerated the collapse as slaves and deserters decided the presence of these men presented an opportune moment for escalated resistance.

Blending rich analysis with an engaging narrative, Foote uses these ragged Union escapees as a lens with which to assess the dying Confederate States, providing a new window into the South’s ultimate defeat.

Blending rich analysis with an engaging narrative, Foote uses these ragged Union escapees as a lens with which to assess the dying Confederate States, providing a new window into the South’s ultimate defeat.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Yankee Plague by Lorien Foote in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Storia & Storia della guerra civile americana. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Escape

The story of fugitive Federals and the collapse of the Confederacy begins in September 1864, when the Confederacy was staggering under myriad external and internal threats to its existence. On the military front, Confederate armies were giving up ground and casualties in every region. In the spring of that year, Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, the newly appointed commander of all Union armies, ordered coordinated offenses in order to apply pressure at all points and take advantage of superior manpower. He was the first general to implement such a strategy during the war. In response, Confederate generals Robert E. Lee in Virginia and Joseph E. Johnston in Georgia adopted defensive maneuvers and entrenched positions that inflicted appalling casualties on Union armies and that seemed to stymie their breakthroughs on both fronts. Impatient and war-weary northerners feared the war had become a stalemate, even though Union armies were on the doorsteps of Richmond and Atlanta, and in August President Abraham Lincoln worried he would not be reelected.

Confederate armies expended maximum blood and treasure to stall Union offensives, yet the enemy continued its heavy punches. In the meantime, the Union’s blockade of the Confederacy contributed to shortages and an inflation rate that reached 9,000 percent in 1864. The blockade was not the only source of economic troubles. The Confederate government printed fiat money without making such currency legal tender. Speculators roamed the country in the guise of Confederate officials, bought produce from hard-pressed farmers, and hoarded the goods to sell at astronomic prices. The drain of manpower from farms to battlefield, the slowdown of work on the part of slaves, the refusal of some planters to grow food for the armies rather than cotton for the blockade-runners, and the incursions of Union armies in various locations caused a downslide in agricultural production. Confederate states implemented welfare programs to provide relief for thousands of soldiers’ wives who could not feed their families.

With these pressing military and economic problems, the Confederacy faced additional political and social turmoil during 1864. President Jefferson Davis battled constant and increasing opposition in the Confederate Congress and from state governors over taxation, conscription policies, and the disposition of Confederate troops. State legislatures passed bills that contradicted national laws in order to keep men out of Confederate armies fighting in Virginia and Georgia. In the Appalachian Mountain regions of Virginia, Tennessee, the Carolinas, and Georgia, thousands of deserters from the Confederate army and disgruntled elements who defied Confederate authority stole provisions from loyal Confederate citizens, attacked state and Confederate units sent to capture them, engaged in guerrilla warfare with Confederates, and contributed to the descent into chaos and anarchy in some counties. Slaves in regions adjacent to Union armies ran away in droves, defied their masters, and constantly watched for opportunities to subvert the Confederacy’s most important economic and social institution.1

Within this context of multiplying and enlarging threats, Union military offensives injected an unexpected element: Federal prisoners of war. According to a cartel established between the Union and the Confederacy in July 1862, prisoners captured in battle were immediately released on parole, which was a signed promise not to fight again until both governments agreed upon an exchange of prisoners. But neither side adhered to the terms of the cartel. The system soon broke down under the weight of mistrust and mutual recriminations. The Confederacy refused to treat African American soldiers who fought for Union armies as prisoners of war and President Lincoln insisted that they do so. By 1864 general exchanges of prisoners stopped. During the massive Union offensives in Virginia and Georgia between May and August, tens of thousands of Federal prisoners accumulated behind the lines in the Confederacy. They were a galling problem that sapped the Confederate infrastructure of manpower and provisions under the necessity of guarding and (barely) feeding them. Grant and U.S. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton were not really interested in exchanging prisoners of war. The Union had an advantage, since it held more prisoners than the Confederacy did. Grant wanted Rebels in northern prison camps rather than in Rebel armies, even if that meant thousands of Union soldiers died of hunger, exposure, and disease in Confederate camps. In the long run, Grant believed, such a policy would end the war faster and ultimately save more lives than it cost.2

The Confederate government shifted thousands of Yankees from Richmond to Georgia when Grant’s offensives filled beyond their capacity the notorious Libby and Belle Isle prisons located in the Confederate capital. Enlisted men, more than 30,000 of them, shipped off to Camp Sumter in Andersonville, and 1,500 Federal officers transferred to Camp Oglethorpe in Macon. The blame for the death and suffering that transpired in these two camps during the summer of 1864 remains contentious to this day. The prisoners believed—most of those who survived never wavered in this belief—that the Confederate government deliberately starved, robbed, and tortured them. Defenders of the Lost Cause, then and now, blamed Lincoln for not exchanging prisoners and Union armies and navies for ravaging southern resources. With Rebel armies going hungry, they claimed, there was nothing to spare for Yankee prisoners. Modern scholarship on Civil War prisons points to the gross incompetence of Confederate authorities who mismanaged every aspect of the prison system, from selecting sites for camps to distributing available stocks of food.3

Confederate mismanagement was on stark display when the movement of Union armies in September 1864 once again necessitated the shifting of Federal prisoners. This time, though, authorities in Richmond unleashed a chain reaction that had vast repercussions in the daily lives of Confederate citizens who lived in the Carolinas. On September 2, 1864, Major General William Tecumseh Sherman captured Atlanta. Samuel Cooper, the Confederate adjutant and inspector general, decided to remove most Federal prisoners from Georgia to keep the Union army from liberating the captives. When he ordered the evacuation of Andersonville and Macon prisons on September 5, there were not adequate shelters prepared anywhere else in the region to house the hungry and ill-clad Yankees. Nor was there an effective command-and-control structure over the Confederate prison system. There was no commissary general of prisoners in September 1864 but rather divided responsibility between Brigadier General John Winder and Brigadier General William Gardner, neither of whom was entirely clear about his lines of responsibility and authority. Winder was in charge of the evacuation, and he decided to send the prisoners to Savannah and Charleston.4

No one bothered to notify Confederate departmental military commanders about the transfer of thousands of prisoners to Savannah. Major General Lafayette McLaws was flummoxed when 1,500 Federal prisoners arrived in the city on September 8. “There must be some strange misconception as to the force in this district,” he protested. “I have now not a single man in reserve to support any point that may be threatened by the enemy. I have no place stockaded or palisaded or fenced in where the prisoners can be kept. No place where there is running water.” McLaws placed an officer in charge of the emergency, who immediately impressed slaves wherever they could be found on the city’s streets. They worked through the night lengthening a three-sided fence that partially enclosed an open area behind the local jail. They left one end open in order to extend the sides as more prisoners arrived. Crews continued to work until September 17, when the stockade reached the capacity to contain 10,000 prisoners.5

Cooper and Gardner did notify Major General Samuel Jones, commander of the Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, that prisoners were on the way from Andersonville to Charleston. They had not, however, consulted him about how the transfer of thousands of prisoners might thwart his defense of a city besieged by ongoing and active Union military operations. On September 8, Jones frankly threatened Secretary of War James A. Seddon that if Union forces advanced he would withdraw all guards from the prisoners and send them out of the city under the care of the railroad companies. “I am compelled to send prisoners of war where I can, not where I will,” an annoyed Seddon responded.6

Jones scrambled to find guards. He contacted Brigadier General James Chesnut Jr., commander of the Confederate Reserves in South Carolina, who had earlier informed Richmond that his entire force was not sufficient to guard the prisoners from Georgia. Chesnut tried to cooperate. He telegraphed Jones on the ninth that he would “call out citizens temporarily.” But on the tenth he reported he could not get “a single man from the militia” to help and that he had to obey orders from Richmond sending the reserves to escort the prisoners to Charleston. “I must respectfully at present decline to take charge of prisoners,” he wrote.7

When more than 1,400 Union officers and nearly 6,000 enlisted men accumulated in Charleston on September 12, Jones again protested furiously to Seddon that he did not have sufficient troops to guard the prisoners and defend the city. A few days later, medical officials reported a yellow fever epidemic. Without notifying prison authorities or consulting anyone in Richmond about locations, Jones removed the Federal prisoners from Charleston. Between September 12 and 18, he sent batches of the enlisted men to Florence and put them in an open field with only a force of 125 South Carolina Reserves to guard them. The prisoners, veterans of a summer in Andersonville prison, immediately mutinied in a desperate attempt to flee the area before Major F. F. Warley could construct a stockade. More than 400 of them broke loose from the guards, plundered the citizens in the vicinity of the camp for food and clothing, and attempted to destroy the railroad. Others headed for the woods in a quest to escape. Two of these were Simon Dufur and George Hull of the First Vermont Cavalry. The night was pitch dark, and Dufur and Hull could not see each other, so they had to talk to keep in contact. The woods were full of fugitives and they heard voices in every direction around them. In the mass confusion, Dufur lost his companion, but soon joined a Wisconsin soldier named Orange Ayers and five men from Michigan. The party raided the outbuilding of a large farmhouse and headed into some nearby swamps.8

When Warley telegraphed to Charleston that his force was completely overpowered and the railroad might be destroyed, Jones immediately deployed the Waccamaw Light Artillery, a cavalry unit, and every infantryman he could spare from Charleston to Florence. Over the next several days, these forces and local citizens patrolled the area and rounded up nearly all of the fugitives. Warley placed an appeal to citizens in the Darlington Southerner and asked them to look out for escaped prisoners and detain them. The cavalry caught Dufur six days after his escape thirty-three miles from Florence. Citizens brought hundreds of others back, some of whom had crossed the line into North Carolina. Only twenty-three of the September mutineers arrived safely inside Union lines. Sixteen of these made an arduous quest to Knoxville, Tennessee, reporting there at various times between November and February.9

Despite the temporary influx of troops from Charleston, Confederate officers in Florence resorted to mobilizing the local population in order to restore order and assert authority over the prisoners. The hastily built stockade, although not complete, was ready to receive the prisoners being guarded in the open field on September 30, and an additional 6,000 were on the way from Charleston. Citizens from the countryside surrounding Florence assembled on that morning, each carrying whatever arms he possessed, and came to the prison site to help put the Yankees inside the new stockade. Prison officials were able to restore order and contain the prisoners only with the help of the local population. Prisoners continued to arrive at the compound without prior notice until the end of November.10

Jones’s precipitous creation of a site at Florence only partially handled the prisoner of war crisis in Charleston. Jones had sent off the enlisted men, but he still had more than 1,500 Federal officers on his hands. He sent them to Columbia on October 5 and 6 with similar disastrous results. An unknown number of Yankees escaped in Charleston as they were marched down King Street to the train station. Slaves, free blacks, white Unionists, and a number of Irish and German immigrants hid these escaped prisoners, sometimes for weeks at a time, while they waited for opportunities to escape the city. The citizens who aided the fugitives used the streets of Charleston as pathways to transfer the Yankees from place to place when Confederate troops searched neighborhoods. Captain William H. Telford, Fiftieth Pennsylvania, traveled through six locations in the city, including a shoemaker’s shop on King Street, a store on Cummings Street, a bachelor’s house on Calhoun Street, and a family residence near the Negro Hospital. Eventually the fugitives ended up on one of the city wharves, where slave pilots moved them out by boat under the cover of darkness to Union lines on Hilton Head. Twenty-six of these fugitive Federals made it safely to the island by January 1865.11

This portrait of J. Madison Drake appeared in Fast and Loose in Dixie (1880).

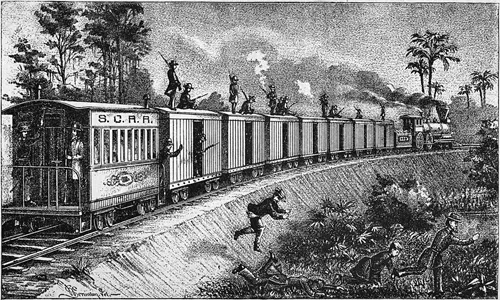

More than 100 Federal officers escaped from the train on the way to Columbia, jumping off at one or the other of its two stops to fill up with water, first at Branchville, then at Kingsville. Among the latter were Lieutenant J. Madison Drake, and Captains Jared E. Lewis, Harry H. Todd, and Albert Grant, who were in the boxcar immediately in front of the caboose. Later, none of them could remember or explain how they survived the landing uninjured. As soon as they stopped rolling, they ran into a dark woods by the side of the railroad tracks, and then into a huge cypress swamp. The plan, forged during hours of studying an old atlas they found in the Marine Hospital where they were kept in Charleston, was to march northwest to the Union lines near Knoxville, Tennessee.12

More than 100 Federal officers escaped from the train carrying prisoners between Charleston and Columbia. Depicted here is the leap of J. Madison Drake and his comrades near Kingsville. Sketch from Fast and Loose in Dixie (1880).

During his exploits as a fugitive inside the Confederacy, J. Madison Drake proved to be the heroic leader of men that his earlier war career foretold. A journalist and foreman of a fire company in Trenton, New Jersey, Drake enlisted immediately after the fall of Fort Sumter in a three-month regiment along with thirty-two other members of the American Hose Company. He recruited do...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations and Maps

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations in the Text

- Introduction: The Plague

- 1: Escape

- 2: The World in Black and White

- 3: They Cover the Land like the Locusts of Egypt

- 4: Guardian Angels

- 5: God’s Country

- 6: A Futile Attempt at Imprisonment

- Epilogue: Terrible Times in the Past

- Note on Sources

- Appendix: Maps

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index