eBook - ePub

Chicago's New Negroes

Modernity, the Great Migration, and Black Urban Life

- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

As early-twentieth-century Chicago swelled with an influx of at least 250,000 new black urban migrants, the city became a center of consumer capitalism, flourishing with professional sports, beauty shops, film production companies, recording studios, and other black cultural and communal institutions. Davarian Baldwin argues that this mass consumer marketplace generated a vibrant intellectual life and planted seeds of political dissent against the dehumanizing effects of white capitalism. Pushing the traditional boundaries of the Harlem Renaissance to new frontiers, Baldwin identifies a fresh model of urban culture rich with politics, ingenuity, and entrepreneurship.

Baldwin explores an abundant archive of cultural formations where an array of white observers, black cultural producers, critics, activists, reformers, and black migrant consumers converged in what he terms a “marketplace intellectual life.” Here the thoughts and lives of Madam C. J. Walker, Oscar Micheaux, Andrew “Rube” Foster, Elder Lucy Smith, Jack Johnson, and Thomas Dorsey emerge as individual expressions of a much wider spectrum of black political and intellectual possibilities. By placing consumer-based amusements alongside the more formal arenas of church and academe, Baldwin suggests important new directions for both the historical study and the constructive future of ideas and politics in American life.

Baldwin explores an abundant archive of cultural formations where an array of white observers, black cultural producers, critics, activists, reformers, and black migrant consumers converged in what he terms a “marketplace intellectual life.” Here the thoughts and lives of Madam C. J. Walker, Oscar Micheaux, Andrew “Rube” Foster, Elder Lucy Smith, Jack Johnson, and Thomas Dorsey emerge as individual expressions of a much wider spectrum of black political and intellectual possibilities. By placing consumer-based amusements alongside the more formal arenas of church and academe, Baldwin suggests important new directions for both the historical study and the constructive future of ideas and politics in American life.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Chicago's New Negroes by Davarian L. Baldwin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Mapping the Black Metropolis

A CULTURAL GEOGRAPHY OF THE STROLL

We can end this review of the institutions, businesses and life of the Negro in Chicago with much self-contentment, if the review of this big city has unsealed the eyes of many, regardless of where they live, who contend that the race has no field for its capital.

—Howard A. Phelps, “Negro Life in Chicago,” Half-Century Magazine, May 1919

—Howard A. Phelps, “Negro Life in Chicago,” Half-Century Magazine, May 1919

The Map of Colored Chicago: Showing the Streets, Street Car Lines, and especially featuring the Colored section, giving the location of all the principal Colored Churches, Colored Hospitals, Lodges, Colored Clubs, Colored Y.M.C.A., Colored Y.W.C.A., and other public places of amusement, recreation and interest.

—Progressive Book Company advertisement, Half-Century Magazine, April 1922

—Progressive Book Company advertisement, Half-Century Magazine, April 1922

Chicago . . . was a real us-for-we, we-for-us community. It was a community of men and women who were respected, people of great dignity—doctors, lawyers, policy operators, bootblacks, barbers, beauticians, saloonkeepers, night clerks, cab owners and cab drivers, stockyard workers, owners of after-hours joints, bootleggers—everything and everybody.

—Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington, Music Is My Mistress, 1931

—Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington, Music Is My Mistress, 1931

THE SPATIAL CONSTRUCTIONS OF RACIAL RESPECTABILITY

Six years before cultural critic Alain Locke made an almost identical (and more famous) claim about the Harlem Renaissance, the impact of the Great Migration encouraged writer Howard Phelps to remark, “Professional men are leaving the South on the trail of their clients and patients who have settled in Chicago.” In the same 1919 essay, Phelps offered an extensive documentation of prominent black church and amusement landmarks complemented by the individual accomplishments of black entrepreneurs and leaders as indications of racial respectability in the city. His Half-Century Magazine essay, “Negro Life in Chicago,” was followed by the Progressive Book Company's 1922 advertisement for a map of the same community. Finally, when musician/composer Duke Ellington visited in 1931, he was equally impressed by Chicago's black institutions and its “community of men and women who were respected” (emphasis added). These various cultural mappings highlight the consistent symbolic importance of black “enterprise” in constructing notions of race pride and in securing the desire for a many times elusive respectability. And yet on first sight, Ellington's inclusion of policy (illegal lottery) operators, saloon keepers, and bootleggers as enterprising might seem out of place and glaringly incommensurate with both Phelps's and the Progressive Book Company's vision of racial respectability.1

Such divergent mappings of the same place and the inclusion of different figures and institutions under the same banner of respect and dignity are significant. They reveal the larger spatial transformations, class conflicts, and ideological struggles that took place in both the physical and conceptual space of the emerging black metropolis. The contested highlights and oversights in the various geographical representations of the metropolis by white observers and black old and new settlers reveal contested interpretations of what a black modernity could mean. These embattled mappings became the terrain upon which Chicago's New Negro life was built.

At the center of the emerging “metropolis” vision stood Chicago's black commercial amusement and business district, the “Stroll.” This chapter examines the same space and time of the Stroll from three different conceptual vantage points, three simultaneously generated and overlapping planes of existence, each competing for community (re)cognition. The space and meaning of the Stroll was pushed and pulled as a battleground over the three basic images of black primitivism, racial respectability, and leisure-based labor. Amid this representational struggle, the Stroll became the spatial articulation of different New Negro intellectual positions on the meaning and use of the black metropolis as both a built environment and an ideal. Yet, the Stroll was not an island unto itself but must be understood as a spectacular manifestation of the international transformations affecting both the community and the city at large.2

FROM BLACK BELT TO BLACK METROPOLIS: SLUMMERS, SOCIAL SCIENTISTS, UPLIFTERS, AND ENTERPRISERS

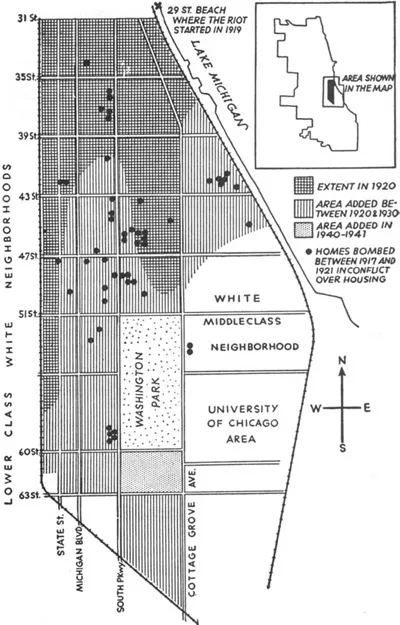

By 1910 and especially after 1915, the ranks of Chicago's black citizenry were rapidly swelling within the cramped spaces of what was called the Black Belt, a narrow strip of land on the south side of the city from 18th Street to 39th Street and bounded by State Street on the east and the Rock Island Railroad tracks and LaSalle Street on the west. As the population exploded from 44,130 in 1910 to 233,903 by 1930, a trend of spatial consolidation restricted the Black Belt's expansion primarily to the south, west to Went-worth, and a few streets east with some black residents as far east as Cottage Grove. Black residents were faced with the “dynamic of choice and constraint” and therefore, unlike other immigrants, were more restricted to residential space along the lines of ethnicity instead of class.3

The force of racist restrictive covenants and racial violence helped materialize the notion of racial restraint quite clearly. Restrictive covenants became legally binding agreements, usually between white real estate agents and owners, to prevent the renting or sale of housing to nonwhites, with threat of civil action. The neighboring Hyde Park, Kenwood, and Woodlawn areas to the south had more available and less expensive housing, but organizations like the notorious Hyde Park and Kenwood Property Owners’ Association went as far as to call on employers to deny jobs to black residents who would dare “invade” white areas. Their general rationale was the protection of property values, but with the financial help of the neighboring University of Chicago, this meant keeping Hyde Park all white. The housing stock left to black residents was in some of the city's most dilapidated neighborhoods. With the rule of restrictive covenants, landlords could extract the highest rents for the worst housing from the most economically disenfranchised population. This reality gave rise to overcrowded housing in the black community and to kitchenettes, where apartments were cut up into single rooms, rented without a lease or, ironically, a kitchen, sometimes including a hot plate for cooking. By 1919, the Black Belt suffered a housing shortage while there was abundant surplus in other parts of the city. Such urban boundaries for housing and leisure mobility were at the same time shaped by racial

Map of the Black Belt. From St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton, Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1945).

violence in the form of young white “athletic clubs” patrolling neighborhood lines and the anonymous firebombing of black homes. Between July 1917 and March 1921, fifty-eight homes in Chicago were bombed, with the predominant victims being South Side black people who had moved into white areas and the black and white agents who had sold to them. This use of restrictive covenants and racial violence racially structured labor, leisure, and living spaces while providing the backdrop for the city's explosive Red Summer of 1919.4

In the midst of the rapid growth and spatial consolidation of the black community, white reformers, reporters, and thrill seekers were not just repelled from (and repelled by) its quarters. They also turned a new eye to what they called the Black Belt and particularly its leisure district, the Stroll, as a site of urban primitivism and pleasure. In response, black leaders hoped to showcase the more respectable “race” enterprises in what they called the metropolis. But all had to concede that the music clubs, movie theaters, beauty parlors, and “sporting dens” on the Stroll were some of the most popular and profitable institutions in the community and so ultimately became the structural foundation for Chicago's New Negro intellectual life.

Located along State Street from 26th to 39th Street, the Stroll was the spatial articulation of New Negro intellectual life within the black metropolis vision. Its major intersection of theaters, restaurants, dance halls, and businesses centered around 35th and State until the late 1920s, when it moved farther south to 47th. This area was variably lauded as “the Bohemia of Colored Folk,” “the black man's Broadway and Wall Street,” and “just like Times Square.” However, these celebratory proclamations were not without context. The Chicago Defender announced that the Stroll was “not so bad as painted—reputable business men and women make up this wonderful thoroughfare.” The paper's sarcastic retort “a careful investigation—or, I might say, visit . . . will show less that tend to be bad” was a direct response to “the white plague” of slummers and pleasure seekers who, according to the Chicago Whip, entered the Stroll “first to scoff and then remain to play” under the guise of uplift, journalism, and/or sociology.5

In newspapers, legislative investigations, and academic studies, black Chicago, among other ethnic enclaves, was represented as the antithesis of Progressive Era industriousness and productivity. At the beginning of the Great Migration, white newspapers screamed “HALF A MILLION DARKIES” bring “PERIL TO HEALTH.” Migrants were demonized as helpless peasant refugees ignorant of urban life with a culture that needed adjustment, containment, and discipline.6 Yet there was still a mix of fascination and fear of the “foreign” culture these migrants carried with them from the South that was simply reinforced by the physical concentration of more black bodies in a confined space. Articles focused on the primitive release and premodern pleasure white tourists thought they found in the race-mixing sites of black-and-tan clubs, buffet flats, and brothels along or near the Stroll. One sensational story described a night at the famous black-owned Pekin Theatre as a miscegenated cauldron of “lawless liquor, sensuous shimmy, solicitous sirens, wrangling waiters, all tints of the racial rainbow. . . . A brown girl sang. . . . Black men with white girls, white men with yellow girls, old, young, all filled with the abandon brought about by illicit whisky and liquor music.” Reporting on a show of famed jazz musician Joe “King” Oliver, Variety described his set as “loud, wailing, and pulsating,” a jazz with “no conscience.” Even those like white jazz musician Eddie Condon, who truly celebrated the Stroll, described this space of black nightlife as having a primitive flair of inherent musicality, as if the “midnight air on State Street was so full of music that if you held up an instrument the breeze would play it.” Black urban space was further depicted as a foreign reserve when the Chicago Tribune described a nearby streetcar line as “African Central.”7

Ironically, as early as 1911, the Vice Commission of Chicago made clear that the link between black life and vice was not a racial inheritance but an intentional project of municipal rezoning that put Chicago's red light district in the black community. Just as in other cities, the rapid growth of Chicago's black population, combined with residential and employment segregation, racist zoning practices, and white violence, confined all black classes, leisure, vice, religion, and so on to the same racially confined space, making the Stroll a perceived model for urban dysfunction and disorganization. The white ownership, operation, patronage, and protection of vice in the Black Belt challenges charges that vice was a “Negro Problem.” However, the spatial fixity of the majority of Chicago's vice and amusement to the geographical location of the Stroll physically marked and conceptually mapped deviance as a “Negro” trait. White tourists could enter, partake of, and enjoy the “vitality” and “spirit” of the African safari in the city, as both a threat and balm that existed outside of and away from their own overindustrialized “white” civilization.8

This nightlife picture of black primitivism was reinforced as “scientific” through the findings of the University of Chicago's “Chicago School” of sociology and its eventual chair and former Urban League president, Robert Park, in particular. The University of Chicago developed a social scientific analysis of urbanization, positing a process of eventual cultural assimilation among different races, to counter the prevalent Social Darwinist theories of inherent biological racial difference and conflict. The integrated emergence of manufacturing industries, urban expansion, ethnic/racial immigration and migration, and conflict made Chicago the perfect “laboratory” for race relations scholarship and reform. Through his human ecology theories, Park argued that social relationships naturally progressed from simple to complex, agrarian to industrial, and primitive rural to civilized urban. The city was seen as a liberating force of natural growth from the confines of the past, and those who did not evolve were unfortunately the dysfunctional causalities of progress.9

At the time, most social scientists used the term “race” where we would now use “ethnicity.” In Park's work, he designated, for example, Jews, Poles, Irish, and Negroes as distinct races with their own “temperaments” that determined the state and speed at which each group would assimilate into the “American” social order. Park built on the popular assumptions of employers to rationalize that all “foreign” racial groupings had deviant temperaments. But in the context of Chicago's entrenched racial violence, it also became clear that the “racial uniform” of “nonwhite” social groups prevented a natural incorporation into the national whole simply through acculturation. However, instead of focusing on the very real systemic and personal resistance on the part of both white citizens and European ethnic immigrants toward black migrant incorporation, Park turned to the Negro's temperament as a rationale. He wrote that black people manifested “an interest and attachment to external, physical things rather than to subjective states and objects of introspection, in a disposition for expression rather than enterprise and action. . . . He is, so to speak, the lady among races.” So if the industrial symbols of “enterprise and action” designated a culture of “civilization,” the Negroes’ specific “disposition for expression” was the natural explanation for their slow advance and their spatial location in urban vice districts. Park later suggested that perhaps the only route to Negro assimilation was through biological miscegenation. He argued that the mixture of white blood and culture was what, for example, made mulattoes like Frederick Douglass and W. E. B. Du Bois less docile and more “aggressive and ambitious.” Negroes could be assimilated, but unlike Poles, Jews, or the Irish, the Negroes’ racial temperament—more so than racism—fixed them as the negation of civilization from the start.10

In The City, the most important co-edited work of urban sociology, Ernest Burgess took Park's theories about “racial temperaments” and literally mapped them out on urban space. The Black Belt and its leisure district, the Stroll (never named), were represented as an unassimilable mass of “free and disorderly life,” different and distinct from the “immigrant colonies—The Ghetto, Little Sicily, Greektown, Chinatown—fascinatingly combining old world heritages and American adaptations.” While he witnessed the possibility of European immigrant “adaptations,” Burgess marked the “excessive increase . . . of southern Negroes into northern cities since the war” as the standard by which to measure disturbance in the natural “metabolism” of urban order.11

The Black Belt appeared to constitute a structurally homogeneous and socially deviant community primarily because of both the legal and informal modes of racial restrictions on mobility. But within the black community, preexisting and newly developing cultural codes profoundly shaped structural realities. Underneath racist visions of the Black Belt as an undifferentiated racial mass existed varied responses to economic, residential, and ideological discrimination attempting to directly refute Park's theory that the Negro had no disposition for “enterprise and action.” Alongside journalistic and sociological observations, black institutions, social mores, and cultural codes continued to develop in black neighborhoods. These enclaves became attractive to those who either chose or were forced into relative exclusion from the white properties of social and physical mobility, especially during the Great Migration.

Across the nation, the years of the Great Migration signaled a moment of “ideological, political and cultural contestation between an emergent black bourgeoisie and an emerging working class.” In Chicago, the same period, roughly between 1910 and 1935, highlighted a point of structural/cultural contact and transformation between the self-described “better class” and the masses, giving life to competing “old” and “new” settler ideologies. The “old” and “new” markers of distinction within the black metropo...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Chicago's New Negroes Modernity, the Great Migration, & Black Urban Life

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction“Chicago Has No Intelligentsia”? CONSUMER CULTURE AND INTELLECTUAL LIFE RECONSIDERED

- Chapter One Mapping the Black Metropolis A CULTURAL GEOGRAPHY OF THE STROLL

- Chapter Two Making Do BEAUTY, ENTERPRISE, AND THE “MAKEOVER” OF RACE WOMANHOOD

- Chapter Three Theaters of War SPECTACLES, AMUSEMENTS, AND THE EMERGENCE OF URBAN FILM CULTURE

- Chapter Four The Birth of Two Nations WHITE FEARS, BLACK JEERS, AND THE RISE OF A “RACE FILM” CONSCIOUSNESS

- Chapter Five Sacred Tastes THE MIGRANT AESTHETICS AND AUTHORITY OF GOSPEL MUSIC

- Chapter Six The Sporting Life RECREATION, SELF-RELIANCE, AND COMPETING VISIONS OF RACE MANHOOD

- Epilogue The Crisis of the Black Bourgeoisie, Or, What If Harold Cruse Had Lived in Chicago?

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index