![]()

PART ONE

A City of Refuge

Emancipation in Memphis, 1862–1866

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

City Streets and Other Public Spaces

In the midst of the Civil War, Louis Hughes told his wife, Matilda, “in low tones” about his intention “to try to get to Memphis.” The Hugheses were being held as slaves by Edmund McGee in Panola County, Mississippi. They knew that “others, here and there, all through the neighborhood, were going,” fleeing to the city that was now under Union Army control. Louis later wrote of how Matilda was overcome with fear at hearing his news. They both understood that “there was a law or regulation of the rebel government … authorizing the hanging of any slave caught running away.” Having a few years earlier suffered the death of their infant twins, losing her husband as well was perhaps more than Matilda could bear to contemplate. But Louis was convinced that he would be among those who would succeed at an escape and, “bent on freedom,” planned a journey back to the city where they had lived with McGee before the war. He set out on his first attempt without Matilda, promising to return for her once he found his way to the city. He returned much sooner, though, having been captured by Confederate “bushwhackers” and spared execution only because one of his captors recognized him as a slave of the McGee family. Two months later, he and Matilda attempted to flee with two other slaves. But this group, too, was captured, tracked down by bloodhounds and returned to their owner to face severe beatings. Finally, on a third attempt, Louis’s determination was rewarded. He and another enslaved man reached Memphis in June 1865. By this point, the Confederacy had been defeated. Knowing “it was our right to be free, for the [emancipation] proclamation had long been issued,” Louis quickly enlisted the aid of two Union soldiers, returned to Mississippi, and, under the protection of Union arms, left the plantation for the last time in the company of Matilda, their newborn baby, and other family and friends. Many among them traveling without hats or shoes, this “tired, dirty and rest-broken” group concluded their long journey and arrived at freedom in Memphis on July 4, 1865.1

Louis later described the remarkable scene he discovered on first reaching Memphis: “The city was filled with [former] slaves, from all over the south, who cheered and gave us a welcome.” He also noted that on his return to the city with his family, “aside from the citizens of Memphis, hundreds of colored refugees thronged the streets. Everywhere you looked you could see soldiers. Such a day I don’t believe Memphis will ever see again—when so large and so motley a crowd will come together.”2 The spectacle of racially integrated city streets and of large numbers of African Americans filling public spaces in celebratory fashion was dramatically different from any of Louis’s memories of the city from a few years before. He later recalled, “I could scarcely recognize Memphis, things were so changed.”3

The changes that Louis found so striking were the product of the mass exodus from slavery—of which he and Matilda were a part—that commenced with the first Union Army presence in Confederate territory during the Civil War. People fleeing slavery, most of whom likely encountered obstacles and risks similar to those of the Hugheses, sought out Union Army lines, the “contraband camps” eventually established by Union Army officials, and especially cities captured by Union forces.4 These cities became oases of freedom for slaves from plantations in the surrounding countryside. “Thousands … in search of the freedom of which they had so long dreamed” flocked to Memphis, Louis Hughes later wrote, transforming this strategic river port into a “city of refuge.”5

Once in this refuge, former slaves acted in anticipation of new rights and freedoms. They took their place as active citizens in the markets, saloons, streets, and other visible centers of public life; in civil institutions such as schools, churches, and benevolent societies; at sites of state authority, such as the courts, police stations, and the Freedmen’s Bureau; and at speaking events and parades. Their actions redrew the racial boundaries that all Memphians experienced in everyday public life, integrating spaces and sharing activities and roles—as workers, students, soldiers, worshipers, participants in public festivals, or litigants in court—with whites in ways unheard of before the war. New visions of race and citizenship were being forged in the city’s public spaces.6

Some whites living in Memphis took these changes in stride—especially many recent white migrants to the city who themselves had been devastated by a costly civil war—and others actively promoted and embraced them, such as the numerous northern missionaries, teachers, and businessmen who came to Memphis during or after the war.7 But other white Memphians responded with hostility in a variety of ways. The city’s conservative newspapers, in both editorial commentary and news reports, condemned the new African American presence in the city, characterizing it as “disorderly,” “lewd,” and “criminal.”8 These reports helped to legitimate the misconduct of many police, who frequently arrested freedpeople under false charges of theft, vagrancy, and prostitution. These arrests were often preceded by or carried out with excessive force.9 Police violence was only magnified as officers continually ran up against not only freedpeople’s resistance but also federal authorities who often intervened on freedpeople’s behalf. During the war, the commander of the occupying Union forces ordered police to cease arresting and punishing under antebellum slave codes refugees arriving in the city. Continuing objections to the conduct of the city police led the army eventually to disband the entire civilian government for “disloyalty” and “incompetence.”10 After the war, local officials and police returned to power but were further limited in their authority over freedpeople by the continued Union military presence, made up largely of black Union soldiers assigned to patrol the city’s streets, and the judicial powers granted to the provost marshal of freedmen and the Freedmen’s Bureau Court. During the years of the war and Reconstruction in Memphis, the freed population, empowered by the federal government, embraced new roles in public life, and many white Memphians responded with resistance to both federal power and the emerging forms of equality, universal citizenship, and inclusion of African Americans in the nation embodied in what they observed around them.

Memphis would receive national attention when resultant tensions culminated in a murderous attack against freedpeople living in the city. This attack, which became known as the Memphis Riot, was in fact a massacre of black Union soldiers and other African Americans by city police and white civilians. Although depicted in the city’s conservative press as the suppression of an uprising of black Union soldiers and as an appropriate response to “negro domination,” the violence appeared to many white northerners as evidence of an unregenerate and unsubdued Confederate South. Northern outrage at events in Memphis contributed to growing support for further action on the part of the federal government to create and protect the civil and political

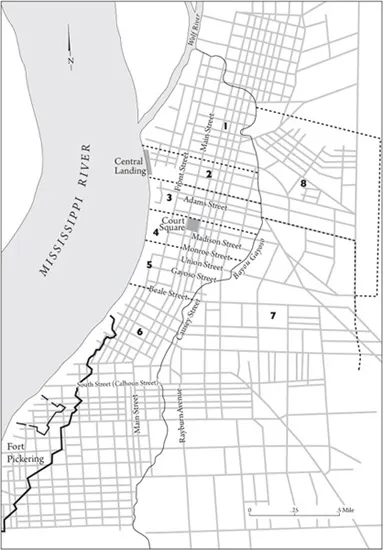

Map of Memphis, Tennessee, 1860s. Wards 6 and 7 composed the neighborhood of South Memphis.

liberties of former slaves. This support led ultimately to the Reconstruction Acts, the first legislative step toward establishing suffrage as a universal right of male citizens of the United States.11 The process of enfranchising black men, then, began, at least in part, in conflicts over public space and race in Memphis.

These conflicts also offer a window onto the central role that gender played in battles over the future meaning and significance of race in a society without slavery. Representations in both the conservative press and police discourses justifying action against freedpeople enlisted constructions of gender, specifically representations of emancipation as the illegitimate empowerment of depraved women and violent men. Similarly gendered representations of African Americans as people who should play only subordinated and marginal roles in public life were voiced in acts of sexual violence suffered by African American women during the Memphis Riot (discussed in Chapter 2). Through both rhetoric and violence, white southern men articulated gendered meanings for race that reaffirmed racial hierarchy, a hierarchy that was being challenged daily by the immediate and profound sign of equality enacted on the stage of the city’s public space.

Urban Spaces, Racial Meanings, and Contests over Rule

Memphis had grown from a small town to a major port city in the decades before the Civil War. Its growth was fueled by an economy deeply rooted in slavery. Sitting high on a cliff overlooking the Mississippi River and, by the 1850s, at the intersection of four railroad lines, Memphis became the main center for trade in the products and needs of a fast-expanding agricultural economy in surrounding Tennessee, Mississippi, and Arkansas.12 That economy’s primary product was cotton—in the 1850s Memphis was often called the “Biggest Inland Cotton Market in the World”13—and its primary need was labor. As a result, the offices of cotton brokers and factors, cotton warehouses, and wagons carrying bales to and from the levee shared space in the city’s commercial district with traders of slaves. More than a dozen such businesses regularly ran advertisements in the city’s newspapers announcing “Negroes for Sale” at their markets on the district’s main thoroughfares, including Main, Adams, Monroe, Union, and Madison Streets and Court Square. Visitors to the city arriving by river were greeted on the steamboat landing by the sign BOLTON, DICKENS & CO., SLAVE TRADERS. Two “slave markets” identified their establishments with large signs hung across from each other on a nearby commercial street.14 The largest slave trader in the city, Nathan Bedford Forrest, bought and sold more than 1,000 slaves annually from his downtown slave market on Adams Street during the 1850s.15

The prominence of slave trading in the city contributed to a visual landscape that, for whites at least, virtually equated blackness with enslavement. Following long-standing patterns, slave dealers often advertised that they were selling “negroes” rather than “slaves.” “Negroes for Sale,” one advertisement read: “A. DELAP & CO. have just received a large stock of South Carolina and Virginia Negroes at their Mart on Adams street, and expect to receive fresh supplies every two to three weeks.” “ACCLIMATED COTTON NEGROES FOR SALE!” ran another, “from the state of Georgia, consisting of men, women, boys and girls. Among them are some very likely families.”16 The language employed in such advertisements moved back and forth between “negroes” and “families” and “sale,” “stock,” and “supplies,” oddly juxtaposing human and commercial terms and ultimately reducing black people to commodities available for purchase by whites.

Also contributing to a conflation of blackness and slavery for whites was the unusually small size of the free population of color and the slavelike constraints under which most free blacks lived in antebellum Memphis. The city’s overall black population was small relative to both the surrounding countryside and other southern cities, comprising 3,882 people, or 17 percent of the city’s inhabitants, in 1860.17 And 95 percent of this population was enslaved, leaving only 198 free black people—less than 1 percent of the overall city population.18 The public conduct of free people of color was strictly regulated by city ordinance.19 Along with slaves, free blacks were prohibited from congregating for political or social activities without permission from the mayor, as well as from public drinking and “loitering in or around the market-house.” Their ability to gather for religious worship, also along with slaves, was limited to observing services at white churches from the balconies or holding prayer meetings in those churches’ basements with a white person present. Indeed, free people of color in Memphis and in Tennessee more generally were increasingly subject to regulations and legal treatment similar to that of slaves.20 In the 1850s, all free black persons were required to register with the city government and to document their employment by a white person (if they intended to remain in Memphis for more than forty-eight hours). They could be stopped and required to show their papers by police at any time. Any person of color found in the city without such papers was presumed to be a slave and, unless he or she could identify an owner living within the city, would be arrested as a runaway.21

Some additional restrictions were imposed only on slaves: city ordinances allowed slaves to move about the city only with passes from their owners, prohibited their “lounging about the streets, drinking or gambling shops,” and forbade them from being outdoors after 9:00 P.M. Slaves were forbidden to live in quarters not owned by their masters and to hire out their own time and labor. Police were instructed to use “corporeal punishment” against slaves found violating these ordinances.22 Such laws could never be fully enforced, especially those requiring slaves to have a pass to move through the city’s streets. An 1858 station register from the Memphis police, for instance, shows large numbers of slaves arrested for being outdoors without a pass.23 This suggests both that enslaved African Americans were able at times to circumvent the constraints imposed by city ordinances and that police were not hesitant to use the power bestowed upon them by the city government to interfere. It does seem that laws against slaves living on their own, as they often did in other cities, were more effective. In Memphis slaves generally lived in close proximity to owners, not among the small free black population, just less than half of whom in 1860 lived in the city’s seventh ward and the rest of whom lived dispersed throughout the city. Ward 7, though, was a majority-white area.24 There were no “black neighborhoods” in Memphis; black residents were integrated into the city in hierarchical and isolating ways. City and state laws regulating the movement and gathering of black people, both free and slave, meant that there were no public spaces with a significant or visible black presence; black institutions and community life were forced largely underground.25

The Civil War permanently altered the racial landscape in Memphis, as public space was suddenly transformed by both the new, free status and dramatic increase in the number of African Americans in the city. The Union Army’s occupation of Memphis in June 1862 almost immediately ushered in thousands of African American migrants. In 1863 the army designated Memphis as the recruiting and administrative center for black troops in the upper Mississippi Valley region, drawing thousands of slaves-turned-soldiers through the city’s streets.26 Seven regiments of black Union soldiers, ultimately comprising 10,000 troops, were stationed at the Union Army’s Fort Pickering, located at the southern edge of the city.27 Following these troops came their family members and other fugitive slaves seeking the protection of the Union forces. Most of these refugees settled near the fort in the neighborhood of South...