![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Prairie Heirs and Heiresses Native American History and the Future of the West in Caroline Soule’s The Pet of the Settlement

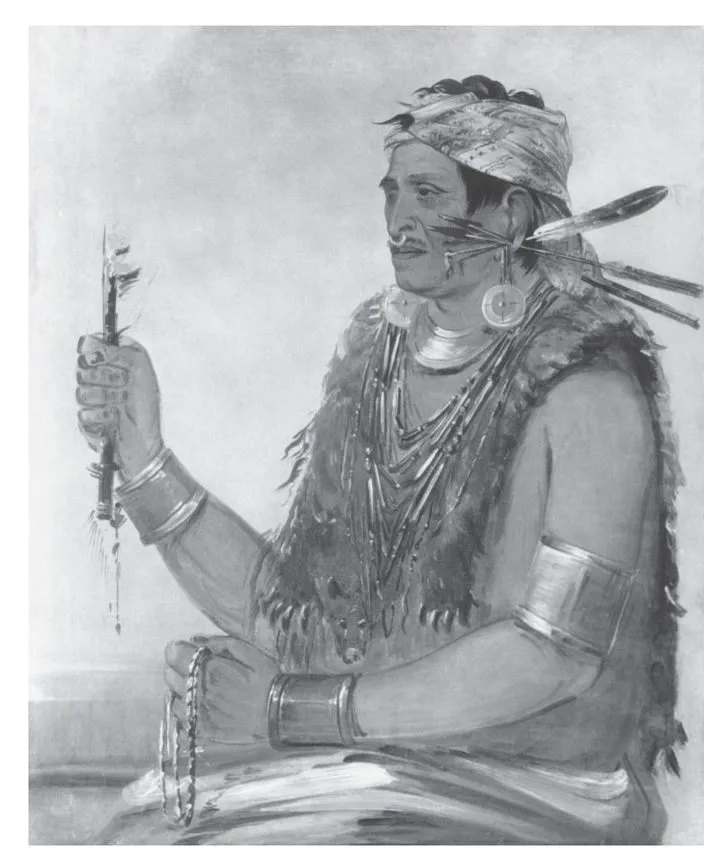

In 1830 George Catlin painted a portrait of Tenskwatawa, the “Shawnee Prophet” and brother of Tecumseh. In the years before the War of 1812, Tenskwatawa traveled widely to urge Indians to look to native religion and ritual in order to fight Euro-American encroachment on indigenous lands and minds. He proposed founding new, pan-Indian towns that would meld tribal identities and herald a new era of political and spiritual unity. But economic and material losses, combined with infighting among the tribes, weakened the movement.1I By 1830, Catlin recalled, the man who was once “quite equal in his medicines or mysteries, to what his brother was in arms” was no longer the powerful force he had been. “Circumstances have destroyed him,” Catlin wrote, “and he now lives respected, but silent and melancholy within his tribe.” In the portrait, Catlin seems to have attempted to capture what he saw as Tenskwatawa’s resignation as well as the ferocity of one who had called thousands to his cause. In The Open Door, Known as the Prophet, Brother of Tecumseh, the one-eyed visionary looks west, holding his “medicine fire” in his right hand and in his left his “sacred string of white beans,” objects he took with him on his journeys (see fig. 1.1). According to Catlin, his “recruits” would swear to his cause by touching the loop of beans.2 Yet the Prophet turns away from his portrait painter, his face haggard and lined, his posture soft, as if remembering a vision. The portrait of the aged Prophet records Catlin’s belief that the perseverance and faith of men like Tenskwatawa was wasted on attempts to salvage a doomed culture.

Catlin’s portraits and writings highlight what he and doubtless many viewers of his Indian Gallery saw as Indian nobility and exoticism. Yet his Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians (1841) show that even as he zealously sought to preserve Indian cultures, he saw them as pertinent to the past, not the future. “I deem it not folly nor idle to claim that these people can be saved,” Catlin wrote, “nor officious to suggest to some of the very many excellent and pious men, who are almost throwing away the best energies of their lives along the debased frontier, that if they would introduce their prayers and plowshares amongst these people . . . they would see their most ardent desires accomplished and be able to solve to the world the perplexing enigma, by presenting a nation of savages, civilized and Christianized (and consequently saved) in the heart of the American wilderness.” 3 Catlin exhorts white men to exercise their manhood by laying aside the pursuit of wealth and power and offering Indians paternal supervision. He imagines the civilizing mission, with its twinned components of Christianization and agriculture, as a nobler enterprise for both border men and Indians.

Author Caroline Augusta White Soule, writing some twenty years after Catlin published his notes, looked at the portrait of the Shawnee Prophet and envisioned an enterprise meant for women. In the preface to her 1860 novel The Pet of the Settlement, she declares that one of her Indian characters, White Cloud, was inspired by “the ‘Shawnee Prophet’ of Catlin.”4 Soule, who may have encountered Catlin’s writings or his traveling portrait gallery as a young woman growing up in the East, also saw the solution to the “Indian Problem” in saving the Indian soul. Yet where Catlin regarded assimilation as an opportunity to create new work for western men, Soule suggests that the very tendency of men to pursue wealth and make war meant that the task of civilizing Native Americans fell naturally to women. Drawing upon the tradition of sentimental literature that lauded white, middle-class women as the moral center of home and nation, Soule’s novel posits that white women who would take on Indians as the objects of their affections could create crucial roles for themselves in colonizing the continent. As teachers and missionaries to the Indians, they could turn moral influence into authority.

Writing in 1860, Soule was informed by decades of domestic writing that cultivated the public image of white, middle-class women as civilizers. Yet in relocating that image to the trans-Mississippi West, Soule’s novel represents an important bridge between sentimental rhetoric and civilization policy. Certainly Soule was not the only domestic writer to imagine the American West as the new moral center of the continent or to suggest that white women would civilize the West. Many of these novels, however, take place within an abstract West that functions as a more moral counterpoint to the industrial East or the slaveholding South.5 In contrast, Soule situates The Pet of the Settlement within a specific geographic, temporal, and political terrain: the landscape of central Iowa that between 1842 and 1860, the years in which her novel takes place, witnessed rapid settlement by whites, the piecemeal takeover of native lands, and the gradual resettlement of the Sauk, Fox, and Ioway beyond the Missouri River. The novel is informed by a period of history that witnessed the difficulties of Indian removal policies, as land cessions forced the tribes into closer proximity with whites and with one another. Soule capitalizes on what she regards as the chaos and violence of male-dominated frontier history, repackaging it in domestic scenarios that intertwine the lives of white women and Indians. In Soule’s hands, the stock sentimental plot of moral regeneration includes Indians; the self-awareness and independence that the heroines achieve depend on their care and instruction of Indians.

Figure 1.1. George Catlin, The Open Door, Known as the Prophet, Brother of Tecumseh. 1830. Courtesy of Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C. / Art Resource,N.Y.

The Pet of the Settlement represents the rewriting of the past that accompanied the attempts of middle-class white women to foresee a new future for themselves and for Native Americans. Yet unlike some earlier writers of historical fiction who appropriated the Indian past, Soule showed an interest less in their wildness or nobility than in their potential for assimilation. She drew on political history, popular representations of Native Americans, and failed Indian policy as well as on the sentimental tradition in creating a western home in which white women preside over their Native American wards. Soule seized on the Prophet Tenskwatawa’s fierce commitment to pan-Indian unity and to religion and ritual as a source of identity in order to harness his influence to a different mission, one that involved white women and natives collaborating to spread Christian domesticity “between the Missouri River and the Rocky Mountains.”6 Prescribing education, landownership, marriage, and Christianity as solutions to the Indian Problem, Soule both presaged the Dawes Act of 1887 and posited these as specific forms through which white women could exercise influence in the West. Soule’s vision resembled Tenskwatawa’s in that it was as forward-looking as it was rooted in tradition and as invested in exerting power through a new political geography as it was in converting souls. She imagined encounters between whites and Indians as opportunities to translate white women’s spirituality and domesticity into sites that would offer women new forms of work in the years to come.

In an Indian Land

In order to imagine a home- and woman-centered future, Soule uses the sentimental genre to domesticate a western past dominated in politics and popular culture by white men and “wild” Indians. Soule admits in her preface that while her tale is based on frontier events related to her by an “aged pioneer,” it is meant to lead the reader “from the shadows of sin and into the sunshine of virtue.”7 In adapting the male pioneer’s story, Soule creates a melodramatic plotline that emphasizes women’s experience and regards domestic ideals as prototypes for national values. The novel echoes Soule’s willingness to rewrite the old pioneer’s story when the heroine, Margaret Belden, appoints a room in her cottage for the crusty old settler Uncle Billy. She decorates it with “pictures of the chase” and fills the bookcase with “tales of hunters, trappers, and Indians, biographies of discoverers and adventures, and volume after volume of natural history.” Yet Uncle Billy rejects the space as too civilized for him, and he moves to his own hut, where he can tell tales of the old days. When Margaret subsequently refurbishes the room for their recently widowed neighbor Grandma Symmes, she replaces the bookshelf and its literary legacy of the frontier with “a commodious dressing bureau,” and in place of images of the chase she hangs pictures with titles like The Healing of the Sick and The Blessing of the Children.8 New inhabitants, Soule suggests, bring new values and necessitate new spaces to house them.

Soule’s novel does not completely reject the western past, for though Uncle Billy must tell his stories elsewhere, Soule makes room in her literary home for Indian characters to take up residence there. Exchanges between white women and their Indian “children” are crucial to the sentimental economy of The Pet of the Settlement, and the circumstances that bring her Native American characters together with their white “mothers” are made possible by a particular history of dispossession. Soule’s domestication of the Iowa prairies depends not only on retelling the old settler’s tale but on reframing conflicts and characters drawn from Native American history. In order to project her tale onto a past marked by uneasy and violent relations between whites and indigenous people, Soule first must clear the landscape by converting indigenous history and politics into literary property.

That effort may partly explain the novel’s numerous digressions and twists of fate. Perhaps because of its awkward blending of gothic melodrama, prairie pastoralism, and sentimental excesses, The Pet of the Settlement has received little critical attention. The plot follows the Belden family — Margaret, her young brother Harrie, and her father — after their arrival in a new Iowa settlement. Early in the novel, the Beldens take in two individuals ripe for the instruction that civilized life has to offer: a Sauk boy named White Cloud and a white baby girl, Allie, the “pet” of the title. As the settlement evolves into a bustling frontier town, Margaret takes on the responsibility of mothering and instructing both Allie and White Cloud. A flashback at midnovel inserts the story of Margaret’s lost love back in New York; when her lover is revealed as the settlement’s mysterious hunter-priest, a prairie wedding ensues. A party of Sioux disrupt the festivities when they kidnap Allie. After White Cloud returns with the girl and a fresh set of scalps, he embarks on a quest to find the girl’s mother. A new subplot reveals that Allie’s mother, Mary, is being held captive by a Sioux chief whose daughter, Bright-eyed, becomes her “dusky maid” and pupil. Eventually, the two Indians collaborate to engineer an escape to the settlement. The mystery of Allie’s appearance on the prairie is solved in another digression, as Mary tells of her husband’s murder and her own kidnapping at the hands of a family friend. Mary’s drawn-out sickness and death and the appearance, absolution, and subsequent death of the murderer conclude the historical section of the novel. The ending reveals the prairie settlement and Belden family fifteen years later, rich in happiness and material success.

This greatly abbreviated summary suggests that Soule’s novel, in fact, has little to do with daily life in the West. Indeed, those who do discuss the novel have found that it fails to wrestle with the realities of the western condition. Henry Nash Smith, in Virgin Land, argues that “the scheme of values in the novel is organized about the superiority of the hero and heroine, whose merits have nothing to do with the West or with agriculture.” He laments that “for all her four years on the prairie, Mrs. Soule can not find the literary means to embody the affirmation of the agrarian ideal her theory calls for.”9 Annette Kolodny, in contrast, suggests that the merits of the heroine and the details of her household have much to do with the way white women envisioned the West. Projecting domestic fantasies onto western landscapes, writers like Soule replaced the brutal realities of western speculation, industrialization, and class division with a nostalgic vision of hearth and home in which women still played vital roles.10 Both Kolodny and Smith emphasize the novel’s engagement with eastern class ideals and find that the novel merely projects a model of virtuous, middle-class white womanhood onto a new environment. Rather than engaging with her western subjects, Kolodny argues, Soule is ultimately interested in developing a “human social garden” in the form of a “model town” that assuages fears about the labor exploitation so rampant in the eastern states.11 Soule exhibits woman’s crucial role in bringing civilization to the prairies, where domestic productivity could flourish without the taint of eastern economic corruption.

Smith and Kolodny are correct in noting that Soule does little to illuminate economic realities or interrogate the social changes brought about by industrialization in the West. For novelists like Soule and for her readers, the prairie landscape provided an ideal setting for dramas of progress that cleansed industrialization of its messier inequities by equating community development with nature’s growth. It is not surprising that establishing middle-class identity in a western environment should entail erasing signs of labor. Making labor invisible was one of the triumphs of middle-class culture and the literature that sustained it; it was rare for a nineteenth-century writer, male or female, western or not, to represent any kind of physical labor as intrinsically valuable.12 Certainly The Pet of the Settlement indicates that the fates of white women did not depend on the economic value of their labor but on their influential domestic role in the gentle “human appropriation of a landscape.”13 In envisioning ideal households ruled by women whose authority issues not from their labor but from their natural domestic tendencies, writers like Soule were complicit in creating a pastoral ideal that concealed the economic value of women’s housework in favor of the more abstract and immaterial concept of women’s influence, a process Jeanne Boydston has termed the “pastoralization of housework.”14

In emphasizing the middle-class, pastoral values that eventually triumph in the novel, however, neither Smith nor Kolodny engages Soule’s portrayal of Native Americans or her appropriation of Iowa history as a backdrop to her novel. Refocusing critical attention on the western materials that Soule does rely on — her Iowa setting and the Sauk and Sioux who play crucial roles in her plot — suggests that Indians are integral to her scheme for establishing middle-class status for white women in the West. Though Soule does seem to exalt the “bright, beautiful change” that comes to the settlement as the open prairie is replaced by a bustling town, her elaborate plot investigates the intertwined histories of the landscape, white women settlers, and the Indians who inhabited the land before the change came about.15 While white women lose some of their more prosaic chores — they can no longer pick wild berries or collect wildflowers when the open prairies have been replaced by private property — the history that left “uncultivated” Indians inhabiting the Iowa landscapes gives white women new forms of work more in keeping with the western narrative of progress.

The Pet of the Settlement is a historical novel set in the decades leading up to the year of the novel’s publication, 1860. Like other American novelists before her, Soule was interested in reconstructing the American past to address present concerns. Soule’s professional and authorial activities point to her involvement in social reform. She was active in the temperance cause, an editor of several religious and women’s periodicals, the first president of the Women’s Centenary Aid Association, and a Unitarian Universalist who eventually became a missionary to Scotland and the first woman ordained as a minister there. Her other writings, Home Life, or, A Peep Across the Threshold (1855) and the temperance tale Wine or Water: A Tale of New England (1862), reflect these interests.16 Her ties with the Unitarian church suggest that she may have been influenced by reform-minded, Christian writers of the previous generation. Lydia Maria Child and Catherine Maria Sedgwick, both Unitarians who wrote of hearth and home, also wrote historical novels about the relationships between white settlers and Native Americans, and their stories may have shaped Soule’s own girlhood. Child’s Hobomok (1824) and Sedgwick’s Hope Leslie (1827) are set in Puritan New England and feature the temporary incorporation of Indians into Puritan homes and white women into Indian ones. Mary Conant’s marriage to Hobomok, Magawisca’s tenure with the Fletcher family in Hope Leslie, and the marriage of Hope’s sister Faith to an Indian all suggest the possibility of native assimilation but fall short of endorsing it. Child and Sedgwick were sympathetic to the Indians’ situation and condemned what they saw as the racism responsible for Indian removal policies, but both were ambivalent about the Indian’s position in the nation. While the women in their novels achieve a measure of independence and carve out roles for themselves as agents in their families and communities, even the most sensitively drawn Indians fade back into the forest. The authors’ interpretations of Puritan en...