- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Long Shadow of the Civil War relates uncommon narratives about common Southern folks who fought not with the Confederacy, but against it. Focusing on regions in three Southern states — North Carolina, Mississippi, and Texas — Victoria E. Bynum introduces Unionist supporters, guerrilla soldiers, defiant women, socialists, populists, free blacks, and large interracial kin groups that belie stereotypes of Southerners as uniformly supportive of the Confederate cause. Centered on the concepts of place, family, and community, Bynum’s insightful and carefully documented work effectively counters the idea of a unified South caught in the grip of the Lost Cause.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

Home Front

LATE IN THE CIVIL WAR, John Beaman of Montgomery County, North Carolina, fired off an angry letter to Governor Zebulon Vance blasting Confederate war policies. Complaining that planters and manufacturers received exemptions from the army while he and other “farmers and mechanics” produced vast quantities of corn and beef, Beaman demanded that the governor explain why he should be forced to “fight for such men as thes[e]?” Around that same time, Romulus Sanders, the sheriff’s son, was charged with stealing a mare from John’s wife, Malinda. These were perilous times for the Beamans, who found their daily lives turned upside down by war.1

John and Malinda Beaman were among the small farmers in the South who vigorously opposed the Confederacy. The couple lived on the Montgomery-Randolph county line where they raised corn, wheat, and hogs alongside neighbors and kinfolk. The upheaval caused by war, however, prompted John Beaman to warn Governor Vance that farmers would be forced to “revolutionize unles this roten conscript exemption law is put down, for they air laws we don’t intend to obey.”2

And revolutionize they did. By late 1863, the Randolph County area in which the Beamans lived was a hotbed of Unionism, desertion, and guerrilla warfare. No isolated example, such pockets of resistance emerged in nonplantation regions throughout the Confederate South.

Chapter 1 of part I tells the stories of three such regions of resistance: the Piedmont Quaker Belt of North Carolina, the Piney Woods of Mississippi, and the Big Thicket of East Texas. Within their respective states, Unionist communities spilled over the borders of several counties, making the phrases “Jones County area,” “Hardin County area,” and “Randolph County area” the most useful ways to designate them. All three communities had solid nonslaveholding majorities, with slaves making up only 10 to 14 percent of their populations. Those who owned slaves were generally the wealthiest citizens in each community, but they did not culturally dominate their neighbors to the extent, or in the manner, commonly associated with plantation regions. Nor did nonslaveholders always defer to or share the worldview of slaveholders, even though some interacted and even intermarried with them.

Using a comparative context, chapter 1 reveals common and unique cultural features that shaped yeoman farmers’ responses to secession and war. The profiles of these three communities’ most notorious guerrilla leaders—Bill Owens, Newt Knight, and Warren Collins—provide further evidence that although similar class issues linked the uprisings across state lines, each setting was distinct, giving each its own particular characteristics.

The most dramatic difference was displayed in the Randolph County area of North Carolina’s Quaker Belt, where dissent among plain folk such as the Beamans was motivated by religious principles as well as class. Not only did these farmers live outside the plantation belt, but they also lived among large populations of Quakers, Moravians, and Wesleyan Methodists.

So important was religion to the Randolph County area uprising and so visible was women’s participation that chapter 2 focuses exclusively on the Quaker Belt to provide a detailed examination of the role of both. Women did far more than wonder and wait while husbands marched off to war or hid in the woods. Take the Beamans’ cousin, Martha Sheets, for example, who was arrested in early 1865 for threatening the sheriff of Montgomery County. Although Sheets’s behavior was hardly typical of Unionist women, it spoke directly to the issues of class and religion, as well as women’s personal desperation, which motivated protest in the Quaker Belt.

In chapters 1 and 2, retaliation by Confederate forces against Union militants and their families is highlighted. Men who hid in the woods rather than serve the Confederacy relied on female kin to feed and shelter them. As a result, women were in danger of harassment and torture and the men were in danger of execution.

The most thoroughly documented example of retaliation against deserters’ wives is the torture of “Mrs. Owens,” wife of guerrilla leader Bill Owens. Deputy Sheriff Albert Pike, of Randolph County, unapologetically recounted his men’s abuse of Owens’s wife to Judge Thomas Settle, who investigated the matter. To Pike and his men, Mrs. Owens was simply an outlaw’s wife, and a mouthy one at that. Over and over, officers and soldiers repeated the dirge that no respectable woman would engage in disloyal behavior and that no disloyal woman therefore deserved the respect of a Confederate soldier. As for himself, Sheriff Pike declared he would not remain “in a country in which I cannot treat such people in this manner.”3

Whereas chapter 1 compares and contrasts guerrilla uprisings in three different states, chapter 2 contrasts women’s wartime experiences in the Randolph County area with that of women in nearby Orange County. Unlike the women of the militant Randolph County area, who boldly and publicly confronted Confederate forces, Orange County’s women rarely challenged Confederate authority, although they frequently complained about food prices and shortages and committed greater numbers of thefts to feed themselves and their families.

These differences reflected counties where economic, political, and ethnic development had diverged over time. Although Orange County was included in the Quaker Belt, by 1860 Quaker cultural influences had been diminished by migrating Virginian, Scots-Irish, and German settlers. Slavery grew more rapidly than in the Randolph County area, creating larger gaps in wealth among citizens and enabling Orange County’s Confederate leaders to suppress Unionist sentiment more easily.

The contrasting behavior of women in two geographically close counties reveals the effects of race, class, and culture on female unruliness. In the heart of the Quaker Belt, Confederate abuse of Unionist women (and sometimes children) outraged both pro- and anti-Confederate citizens, encouraging militant Unionism and mistrust, even hatred, of Confederate soldiers.

CHAPTER ONE

Guerrilla Wars

Plain Folk Resistance to the Confederacy

From their states of Mississippi, Texas, and North Carolina, Newt Knight, Warren Collins, and Bill Owens led guerrilla bands that waged war on the Confederacy. By early 1864, the most infamous of the bands, headed by “Captain” Newt Knight, had crippled the government of Jones County, Mississippi. Thanks to historians, novelists, moviemakers, and a long-standing family feud, his “Free State of Jones” is the best known of the uprisings. All three of these Unionist uprisings, however, generated regional inner civil wars. Each challenged the Confederacy on its own turf and struggled to restore the power of the U.S. government.

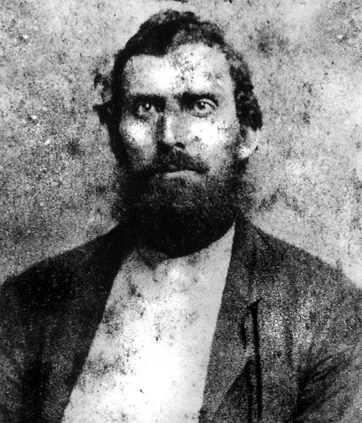

As for the leaders themselves, they possessed forceful, even charismatic, personalities. Newt Knight, a tall, eagle-eyed, and remarkably self-possessed man with extensive family ties in the community, quickly rose to prominence among deserters after escaping his Confederate captors, who, early in 1863, tried to force him back into the Confederate Army. Later that same year, deserters from the Jones County area formally organized themselves, unanimously electing him as “captain” and naming their “company” after him.

Newt Knight, captain of the Knight Company, the guerrilla band that held sway over Jones County, Mississippi, during the Civil War. Photograph courtesy of Earle Knight.

Befitting the leader of a guerrilla band, Newt could be ruthless as well as charismatic. The cold-blooded murder of Major Amos McLemore, Jones County’s most powerful Confederate officer, is universally attributed to Newt, although he was never charged in court. That murder, committed on 5 October 1863, triggered formation of the Knight Company.1

In contrast to Newt Knight, Warren Collins, of Hardin County, Texas, appeared more adept at eluding capture than at murdering Confederate leaders. Not that Collins was necessarily less capable of murder—his reputation as a backwoods, bare-knuckled fighter suggests otherwise. But an entire body of folklore surrounds the life of this so-called Daniel Boone of East Texas, in which he appears more as trickster than as guerrilla leader. His home, the Big Thicket of East Texas, encompassed all or parts of five counties. Distant and isolated from major theaters of the Civil War, the Big Thicket offered an almost impenetrable fortress for the men it sheltered.2

By all accounts, Bill Owens, of North Carolina, appears to be the most ruthless and least charismatic of the leaders. Owens’s Civil War exploits inspired no romantic tales of heroism, and one searches the internet in vain for even one genealogy site that claims him. In fact, it seems Owens has been disowned. Perhaps because the North Carolina Piedmont boasted such an array of articulate Unionists among its political, intellectual, and religious leaders, Owens is known in popular memory (if remembered at all) only as one of the war’s many terrifying outlaws.3

More positively remembered leaders from the Randolph County area include militant Unionist Bryan Tyson, who was descended from Quakers, and Daniel Wilson and Daniel Worth, both of whom were Wesleyan Methodist abolitionists. Hinton Rowan Helper, author of the free soil/abolitionist tract The Impending Crisis of the South, was from nearby Davie County, and John Lewis Johnson, founder of the underground Unionist organization the Heroes of America, was from Forsyth County, another Quaker Belt county.4

Particularly in the Piedmont’s Randolph County area, where Bill Owens was born and raised, religious principles as well as class interests motivated loyalty to the Union. The same cannot be said of the uprisings in Jones County, Mississippi, and Hardin County, Texas, where religious irreverence rather than piety may have diluted the effects of pro-Confederate sermons. Neither Newt Knight nor Warren Collins appeared to be particularly devout. Nor is there evidence of organized abolitionist activity among families who rallied in support of either the Mississippi or the Texas uprisings.5

Despite a less ideological reputation than his Quaker and Wesleyan Methodist

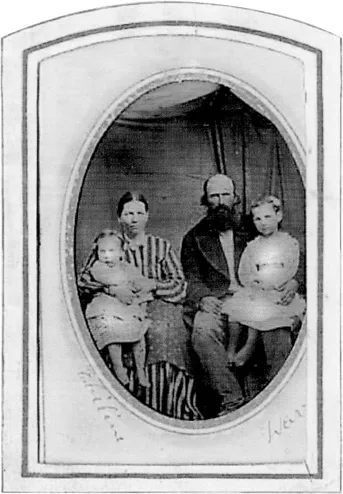

Family of Warren Jacob Collins, leader of the jayhawker guerrillas who hid out in the Big Thicket of East Texas during the Civil War. Seated on the left is his wife, Tolitha Eboline Valentine. On their laps are daughters Cora and Lillie. Photograph courtesy of Mary Allen Valentine Murphy.

peers, Bill Owens was solidly rooted by kinship and neighborhood in North Carolina’s Unionist networks. Nearby kin included Murphy Owens, age forty-two, of Montgomery County, a self-proclaimed Union man, and Joseph Owens of Moore County, a cousin or perhaps even a brother, who refused to join the Confederate Army and protested the forced conscription of his sixteen-year-old son, Daniel, in 1864.6

Historians continue to struggle to understand the guerrilla bands that roamed the South during the Civil War. The communities of dissent that produced Newt Knight, Warren Collins, and Bill Owens were located in widely separated states and provide an opportunity to study Southern Unionism in a comparative context. Each man’s community differed in expression and level of dissent, demonstrating the importance of physical, economic, and political environments, as well as community traditions and cultural beliefs, in generating sustained resistance to Confederate authority.7 Despite wide distances between the communities, they are linked to one another by migration patterns from the settled East to the Southwest and onward to the West. In the wake of the American Revolution, families migrated from the backcountry of North Carolina to that of South Carolina and then on toward Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi. The quest for fresh forests and grazing lands amid expanding plantation agriculture continued into Texas, particularly after its annexation to the United States in 1845.

But the connections among these communities are about more than migration patterns. North Carolina was the ancestral seedbed for migrants to Jones County, Mississippi. In turn, many citizens of Jones County moved on to East Texas before the Civil War. Somewhere between North Carolina and Mississippi, Newt Knight’s Quaker heritage was replaced by Baptist allegiances. And, in Texas, Warren Collins of Mississippi entered a state where prosecession rhetoric would be tied to Texas’s 1836 revolution and its annexation a decade later to the United States.

Still, similarities among the communities are striking: most obvious are their locations outside the cotton belt, which extended across the South. In all three, men who deserted the Confederacy received strong civilian support, not only for rejection of Confederate military service but also for waging war on the Confederate government. Men hid in the woods to avoid conscription but also organized and armed themselves for battle much like any regular soldier. Extensive ties of kinship and neighborhood were essential, and women, children, and slaves aided their missions.8

Genealogical research on participants in the Free State of Jones confirms both their kinship and their migration patterns. Twenty-six of the fifty-five men who made up the core of the Knight Company carried the surnames of Collins, Knight, Valentine, Welch, Welborn, and Whitehead. The ancestors of these men were chief among the region’s founding families, many having intermarried with one another for several generations—in some cases long before entering Mississippi Territory. As a result, all were related either to Captain Newton Knight or to his first and second lieutenants, James Morgan (“Morgan”) Valentine and Simeon Collins. More accurately, this was the Knight-Valentine-Collins band.9

The ancestry of Texas’s Warren Collins epitomized the frontier trail that linked the three Southern regions. His father, Stacy Collins, left the South Carolina backcountry as a young man, settling in Georgia, then Mississippi, then Texas. Along the way, around 1808, he met and married Sarah Anderson Gibson, of Georgia. The Collinses arrived in Mississippi Territory around 1812. By 1826, the year that Jones County was formed in the state of Mississippi, they and their allied families were settled farmers and herders who chose not to own slaves despite its increasing popularity throughout the South.10

By 1850, ten of Stacy and Sarah’s fourteen children were married with families of their own and were among the most prosperous and civic minded of Jones County’s nonslaveholding farmers. For some, the frontier once again beckoned. Shortly before 1850, the Collinses’ oldest child, Nancy Riley, moved to Texas with her husband; in 1852, sons Stacy Jr., Newton, and Warren followed suit. Though getting on in years, Stacy Sr. and Sarah decided to accompany them. They and their youngest child, Edwin, age twelve, packed their belongings and joined the caravan west. Remaining in Mississippi were brothers Vinson, Simeon, Riley, and Jasper and two sisters, Sarah Parker and Margaret Bynum.11

In the dense forests of the Big Thicket of East Texas, the Collins brothers farmed less land and raised more hogs. They built homes from seemingly endless pine trees, planted corn, built smokehouses, and purchased a few cows for milk. Wild game and hogs from the surrounding woods supplied their meat. Warren Collins so preferred East Texas to Mississippi that he returned to Jones County in 1854, married Eboline Valentine, and brought her back with him. For this couple, settling in Texas continued their ancestors’ precedent of leaving societies in which slavery was on the rise. During the Civil War, the Big Thicket of East Texas provided ref...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- The Long Shadow of the Civil War

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Preface

- INTRODUCTION: Kinship, Community, and Place in the Old and the New South

- PART I Home Front

- PART II Reconstruction and Beyond

- PART III Legacies

- EPILOGUE: Fathers and Sons

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgments

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Long Shadow of the Civil War by Victoria E. Bynum in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.