![]()

1 | HOW CAN WE DEFINE DOCUMENTARY FILM? |

Enter the Golden Age

The current golden age of documentaries began in the 1980s. It continues unabated. An abundance of films has breathed new life into an old form and prompted serious thought about how to define this type of filmmaking. These films challenge assumptions and alter perceptions. They see the world anew and do so inventively. Often structured as stories, they are stories with a difference: the stories stem from the world we all share. In a time when the major media recycle the same stories on the same subjects over and over, when they risk little in formal innovation, when they remain beholden to powerful sponsors with their own political agendas and restrictive demands, it is the independent documentary film that has brought a fresh eye to the events of the world and has told stories, with verve and imagination, that broaden horizons and awaken new possibilities.

Documentary has become the flagship for a cinema of social engagement and distinctive vision. The documentary impulse has rippled outward to the internet and to sites like YouTube, Vimeo, Vine, and Facebook, where mock-, quasi-, semi-, pseudo- and bona fide documentaries, embracing new forms and tackling fresh topics, proliferate. The internet and its next-to-nothing costs of dissemination, along with its unique forms of word-of-mouth enthusiasm, combined with the hunger of many for fresh perspectives and alternative visions, give the documentary form a bright and vibrant future.

The Oscars from the mid-1980s onward mark the ascendancy of the documentary as a popular and compelling form. Never known for its bold preferences, often sentimental in its affections, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences has nonetheless been unable to help itself when it comes to acknowledging many of the most outstanding documentaries of the current golden age. Consider just some of the Oscar nominees since the 1980s:

∙The Times of Harvey Milk (1984), about the pioneering gay activist and politician Harvey Milk.

∙Runner-ups Radio Bikini (1987), about the atomic bomb blast that resulted in radiation death and injury to many, and Eyes on the Prize (1987), the epic story of the civil rights movement.

A significant influence on the acclaimed 2008 feature film, Milk, with Sean Penn as Harvey Milk, this documentary traces the career of the first openly gay political figure. The Times of Harvey Milk (Robert Epstein and Richard Schmeichen, 1984). Courtesy of Rob Epstein/Telling Pictures, Inc.

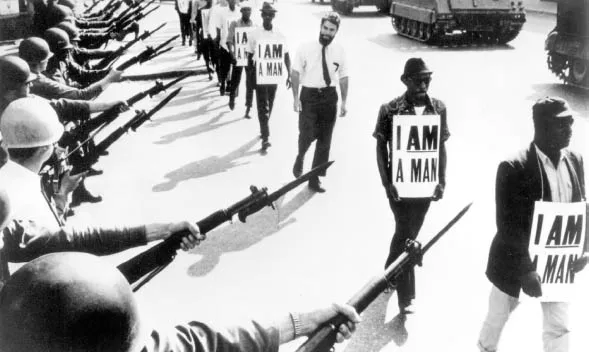

The film depends heavily on historical footage to recapture the feel and tone of the civil rights movement of the early 1960s. The capacity of historical images to lend authenticity to what interviewees tell us makes their testimony all the more compelling. Eyes on the Prize (Henry Hampton, 1987). Courtesy of Blackside Inc./Photofest.

∙Hotel Terminus (1988), about the search for the infamous Nazi Klaus Barbie, and runner-up Christine Choy and Renee Tajima-Peña’s Who Killed Vincent Chin? (1988), about the murder of a young Chinese American man whom an unemployed Detroit autoworker attacked, partly out of irrational rage at the success of the Japanese auto industry in their competition with domestic car makers.

Throughout the film, the directors draw on footage taken by local television stations as well as their own footage to explore what led to Vincent Chin’s murder. This shot is a still camera shot taken by the filmmakers as television crews jockeyed to cover the event as well. The victim’s mother is speaking at a rally with the Reverend Jesse Jackson in attendance. Who Killed Vincent Chin? (Renee Tajima-Peña and Christine Choy, 1988). Courtesy of the filmmaker.

This film won the Oscar in 2013 for its portrayal of some of the most successful backup singers in rock and roll. Never eager for the spotlight per se, they nonetheless contributed to the unforgettable quality of numerous songs. In another scene in the film, Merry Clayton joins Mick Jagger on the chorus to “Gimme Shelter.” The result is a scene of unforgettable power. 20 Feet from Stardom (Morgan Neville, 2013). Courtesy of Radius-TWC and Tremolo Productions.

∙American Dream (1990), Barbara Kopple’s penetrating study of a prolonged, complex labor strike, and runner-up Berkeley in the Sixties (1990), a rousing history of the rise of the free speech and the anti–Vietnam War movements.

∙Super Size Me (2004), Morgan Spurlock’s humorous but also serious indictment of the fast food industry, dramatizing by his attempt to live on a diet of nothing but fast food for the duration of the film.

∙Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room (2005), about the implosion of Enron and the corporation’s leaders who exploited others for personal gain.

∙March of the Penguins (2005), about the fate of the penguin population of Antarctica.

∙Trouble the Water (2008), about events during and after Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans.

∙Exit Through the Gift Shop (2010), a complex portrait of graffiti artists and the strange twists that befall the filmmaker.

∙Gasland (2010), a powerful, disturbing examination of the issues involved in fracking.

∙5 Broken Cameras (2011), the story of an apolitical Palestinian farmer forced to confront intrusions by the Israeli army.

∙Searching for Sugar Man (2012), recounting the search for a hugely popular American singer who disappears and may be dead even though he remains immensely popular in South Africa.

∙The Act of Killing (2012), a stunning account of mass murder in Indonesia, told and reenacted by the killers.

∙Twenty Feet from Stardom (2013), a rousing portrait of the lives of some of the best backup singers in music, both on stage and off.

∙Citizenfour (2014), a clear-headed portrait of Edward Snowden, the man who exposed the US government’s clandestine surveillance programs.

∙Virunga (2014), a moving examination of the political tensions that cloud the future of this national park in the Congo, home to mountain gorillas and rich deposits of oil.

Like scores of other films that have found national and international audiences at festivals, in theaters, and on cable and websites, these films attest to the resounding appeal of the documentary today. The spoken voices of filmmakers like Jonathan Caouette (Tarnation, 2003), Morgan Spurlock (Super Size Me, 2004), Zana Briski (Born into Brothels, 2004), and, of course, Michael Moore (Fahrenheit 9/11 [2004] and Sicko [2007]) remind us that these filmmakers maintain their distance from the authoritative tone of corporate media in order to speak to power rather than embrace it. Their stylistic daring—the urge to stand in intimate relation to a historical moment and those who populate it—confounds the omniscient commentary of conventional documentary and the detached coolness of television news. Seeking to find a voice in which to speak about subjects that concern them, filmmakers, like the great orators of the past, speak from the heart in ways that both fit the occasion and issue from it.

The Search for Common Ground: Defining Documentary Film

Given the vitality of expression, range of voices, and dramatic popularity of documentary film, we might well wonder what, if anything, all these films have in common. Have they broadened the appeal of documentary by becoming more like feature fiction films in their use of compelling music, reenactments and staged encounters, sequences or entire films based on animation, portrayals of fascinating characters, and the creation of compelling stories? Or do they remain a fiction (un)like any other? That is, do they tell stories that, although similar to feature fiction, remain distinct from it? This book will answer in the affirmative: documentaries are a distinct form of cinema but perhaps not as completely distinct as we at first imagine.

A concise, overarching definition is possible but not fundamentally crucial. It will conceal as much as it will reveal. More important is how every film we consider a documentary contributes to an ongoing dialogue that draws on common characteristics that take on new and distinct form, like an ever-changing chameleon. We will, however, begin with some common characteristics of documentary film in order to have a general sense of the territory within which most discussion occurs.

It is certainly possible to argue that documentary film has never had a very precise definition. It remains common today to revert to some version of John Grierson’s definition of documentary, first proposed in the 1930s, as the “creative treatment of actuality.” This view acknowledges that documentaries are creative endeavors. It also leaves unresolved the obvious tension between “creative treatment” and “actuality.” Creative treatment suggests the license of fiction, whereas actuality reminds us of the responsibilities of the journalist and historian. That neither term has full sway, that the documentary form balances creative vision with a respect for the historical world, identifies, in fact, one source of documentary appeal. Neither a fictional invention nor a factual reproduction, documentary draws on and refers to historical reality while representing it from a distinct perspective.

Commonsense ideas about documentary prove a useful starting point. As typically formulated, they are both genuinely helpful and unintentionally misleading. The three commonsense assumptions about documentary discussed here, with qualifications, add to our understanding of documentary filmmaking but do not exhaust it.

1. Documentaries are about reality; they’re about something that actually happened.

Though correct, and although built into Grierson’s idea of the “creative treatment of actuality,” it is important to say a bit more about how documentaries are “about something that actually happened.” We might say, “Documentary films speak about actual situations or events and honor known facts; they do not introduce new, unverifiable ones. They speak directly about the historical world rather than allegorically.” Fictional narratives are fundamentally allegories. They create one world to stand in for another, historical world. (As allegory or parable, everything has a second meaning; what is seen to happen therefore may constitute a disguised commentary on actual people, situations, and events.) Fictions can invent dialogue, scenes, and events that, even if they are based on facts, cannot be historically verified in order to offer insights and generate themes about the world we inhabit. Within an alternative fictional world, a story unfolds. Ideally, it reveals to us aspects of the human condition.

Documentary films, though, refer directly to the historical world. Documentary images present people and events that belong to the world we share rather than invent characters and actions to tell a story that refers to our world obliquely or allegorically. One consequence is that documentaries strive to respect known facts and offer verifiable evidence. They do much more than this, but a documentary that distorts facts, alters reality, or fabricates evidence jeopardizes its own status as a documentary. (For some mockumentaries and for some provocative filmmakers, this may well be exactly what they set out to do. This Is Spinal Tap [1984] and David Holzman’s Diary [1968] are prime examples of this possibility.)

2. Documentaries are about real people.

A more accurate statement might be, “Documentaries are about real people who do not play or perform roles as actors do.” Instead, they “play” or present themselves. They draw on prior experience and habits to be themselves in front of a camera. They may be acutely aware of the camera’s presence, which, in interviews and other interactions, they address directly. (Direct address occurs when individuals speak directly to the camera or audience; it is rare in fiction, where the camera functions as an invisible onlooker most of the time.)

Real people, or social actors, as Erving Goffmann pointed out several decades ago in his book The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1959), present themselves in everyday life in ways that differ from a consciously adopted role or fictional performance. A stage or screen performance calls on the actor to subordinate his or her own traits as an individual to represent a specified character and to provide evidence through his or her acting of what changes or transformations that character undergoes. The actor remains relatively unchanged and goes on to other roles, but the character he or she plays may change dramatically. All of this requires training and relies on conventions and techniques.

The presentation of self in everyday life involves how a person goes about expressing his or her personality, character, and individual traits rather than suppressing them to adopt an assigned role. We learn to do this as we grow up. The presence of a camera is not very different from meeting a new person. We play ourselves in one of the many ways we have learned to do so: friendly, guarded, seductive, charming, persuasive, deceptive, cunning, or cruel. We’ve rehearsed presenting aspects of ourselves many times before. To adopt a new persona, be it friendly or manipulative, domineering or subdued, in an unfamiliar manner usually takes the training expected of an actor. The self we present may have multiple facets, but this is just what the camera captures.

In other words, a person does not present in exactly the same way to a companion on a date, a doctor in a hospital, his or her children at home, and a filmmaker in an interview. Nor do people continue to present the same way as an interaction develops; they modify their behavior as the situation evolves. Friendliness invites a friendly presentation of self, but the introduction of a sarcastic remark may prompt guardedness. Embarrassment or determination may blossom in front of the camera, and in a documentary, we assume this quality stems from the social actor’s own persona rather than from a role they’ve been asked to play. Films such as Battleship Potemkin (1925), Bicycle Thieves (1948), Salt of the Earth (1954), and Shadows (1960) and TV shows like Real World and Survivor give us untrained social actors playing roles that they seem to inhabit naturally, yet the roles are so strongly shaped by the filmmaker or producers that these works are usually treated as fiction. We may assign more realism to certain forms of fiction than they deserve, although some reality TV shows consciously create a blurry boundary between the actual people depicted and the role they seem to adopt at the bequest of the show’s creators.

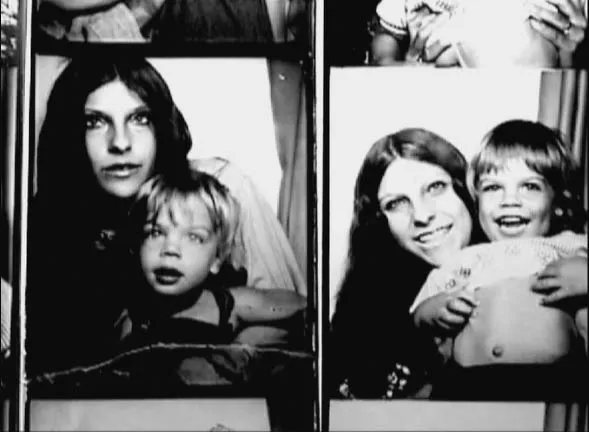

The filmmaker recounts his turbulent family life in a highly performative, moving manner. Renee, his mother, figures as a central part of the story, as does the filmmaker’s love for dressing up, playing roles, and performing for others from an early age. It is one part family drama and one part coming-out story that captures well the complex ways in which we present ourselves to others. This image comes from a photo booth where Renee sits on a stool, poses with Jonathan, and a camera snaps four shots, which are then dispensed to the subject in a minute or two—an analog v...