eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Drama-based Pedagogy

Activating Learning Across the Curriculum

- 260 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

About this book

Drama-based Pedagogy examines the mutually beneficial relationship between drama and education, championing the versatility of drama-based teaching and learning designed in conjunction with classroom curricula. Written by seasoned educators and based upon their own extensive experience in diverse learning contexts, this book bridges the gap between theories of drama in education and classroom practice.

Kathryn Dawson and Bridget Kiger Lee provide an extensive range of tried and tested strategies, planning processes, and learning experiences, in order to create a uniquely accessible manual for those who work, think, train, and learn in educational and/or artistic settings. It is the perfect companion for professional development and university courses, as well as for already established educators who wish to increase student engagement and ownership of learning.

Kathryn Dawson and Bridget Kiger Lee provide an extensive range of tried and tested strategies, planning processes, and learning experiences, in order to create a uniquely accessible manual for those who work, think, train, and learn in educational and/or artistic settings. It is the perfect companion for professional development and university courses, as well as for already established educators who wish to increase student engagement and ownership of learning.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Drama-based Pedagogy by Katie Dawson,Bridget Kiger Lee in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Performing Arts. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Why Use DBP?

Chapter 1

Origins of Drama for Schools’ Drama-Based Pedagogy

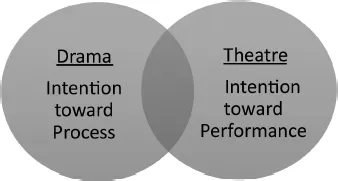

In our practice, the term “Drama-Based Pedagogy” has emerged as a productive way to describe a specific approach that uses drama techniques to teach across the curriculum in the United States public schools. Generally, practitioners and researchers refer to theatre as work that is oriented toward a performative1 product, whereas drama is work that is oriented toward a non-performative process or “process oriented” (see Figure 1). The intention of drama is often characterized as exploratory and reflective; it is work that springs from inquiry. Theatre’s intention is often focused on the creation and reception of a product for an audience. This is not to suggest that there is a fixed dichotomy between theatre and drama. Certainly, drama-based work can move toward a production, and theatre-based work can engage in reflective practice in preparation for a performance. For this book, Drama-Based Pedagogy privileges the process of drama over the product or performance of theatre. However, the practice of theatre remains a central and necessary underpinning of the work.

Drama’s process-oriented use in the classroom and across the curriculum has been described and theorized by scholars and researchers across multiple fields since the middle of the twentieth century. Recent scholarship that influences our work includes writing from areas as diverse as education, literacy, social studies, and social justice/equity (Anderson, 2012; Boal, 2002; Bolton & Heathcote, 1995; Edmiston, 2014; Edmiston & Enciso, 2002; Grady, 2000; Miller & Saxton, 2004; Neelands & Goode, 2000; Nicholson, 2011; Taylor, 1998; Thompson, 1999; O’Neill, 1995; Pendergrast & Saxton, 2013; van de Water, McAvoy & Hunt, 2015; Wagner, 1998). Drama and theatre work in educational contexts goes by many names including drama in education, theatre in education, applied drama, applied theatre, educational drama, dramatic inquiry, role-play, creative drama, improvisation, and Theatre of the Oppressed techniques. The strategies and methods described in this book have their roots in various lines of drama and theatre, but primarily come from the key drama teaching practices that teachers and teaching artists have developed and used in classrooms. For ten years, we have worked in partnership with teachers across the United States to pilot and structure this wide range of drama practices into a flexible, methodological toolkit that supports generalist classroom educators in their efforts to teach for effective learning across all disciplines. Our adaptation of these approaches focuses on “the integration and blurring of the boundaries between personal and social learning and academic learning; learning between subjects as much as within them” (Neelands, 2009, p. 177).

Figure 1: Relationship between drama and theatre.

Note

1 We use the term “performative” to suggest both a “relationship to artistic performance” as well as a reference to the performance “of a social or cultural role” (http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/us/definition/american_english/performative).

Chapter 2

What Is Drama-Based Pedagogy?

What is Drama-Based Pedagogy?

Drama-Based Pedagogy (DBP) uses active and dramatic approaches to engage students in academic, affective and aesthetic learning through dialogic meaning-making in all areas of the curriculum.

As discussed in the previous section, we use the term “drama-based” to describe this practice because the collection and codification of strategies presented in this book are adapted primarily from the field of drama. We use the term pedagogy in this book to focus on the theoretical or philosophical understanding of teaching and learning (Watkins & Mortimore, 1999). DBP offers educators tools and a structure to activate their pedagogical beliefs that align with sociocultural (Vygotsky, 1978) and critical theories of learning (Freire, 2007; hooks, 1994) in the classroom, where participants co-construct their understanding and personal identities as part of the classroom culture.

This chapter explores the theories behind three foundational concepts that are named in our DBP definition: (1) active and dramatic approaches; (2) academic, affective, and aesthetic outcomes; and (3) dialogic meaning-making. When relevant, each concept is discussed through an educational and a drama lens. By discussing both perspectives, teachers may better understand the foundational work of drama and artists may better understand the foundational work in education that informs Drama-Based Pedagogy. Key questions and sections from the example of practice at the beginning of Part I are also included as ways to illuminate and navigate the terrain.

Why does Drama-Based Pedagogy use “active and dramatic approaches”?

Drama-Based Pedagogy uses strategies that bring together the body and the mind through the art of drama/theatre. As others have noted (Edmiston, 2014), both active and dramatic approaches are necessary to fully realize the potential of drama-based inquiry. In DBP participants actively work as an ensemble to imagine new possibilities and to embody and make meaning as a way to situate understanding within the larger narrative/story of the human condition. For example, in the DBP example of practice that began Part I, students were given the opportunity to work as an ensemble, to imagine and embody a possible story about a brown paper bag with a hole on the bottom, a princess, and a dragon. In the next section, we explore how DBP engages in ensemble, imagination, embodiment, and narrative/story as a central aspect of its active and dramatic approach to learning.

To begin, the teacher invites the kindergarten students to sit in a circle on the classroom rug.

Ensemble: DBP offers a way to engage students as a community of learners or an ensemble. As suggested by US theatre scholar and practitioner Michael Rohd, ensemble is “at its simplest, a group of people that work together regularly. At its best, a group of people who work well together, trust one another, and depend upon each other” (2002, p. 28). Drama in education practitioner and researcher Jonathon Neelands furthers this argument when he writes that students in an ensemble “have the opportunity to struggle with the demands of becoming a self-managing, self-governing, self-regulating social group who co-create artistically and socially” (2009, p. 10). Building trust, finding the way through struggle, and learning how to co-create as a community of learners are key artistic skills in DBP that enable students to comfortably use their imagination and body within narrative/story.

There’s a sense of play, now, on our whole campus.

—Fourth Grade Teacher, Texas

—Fourth Grade Teacher, Texas

In educational contexts, ensemble is often described as a sense of belonging, community or relatedness among peers (Anderman, 2003; Ryan & Deci, 2000; Osterman, 2010). Educational theorist, John Dewey argued that the quality of education could be marked by “the degree in which individuals form a group,” (1938, p. 65) and characterizing the group as one that acts “not on the will or desire of any one person […] but the moving spirit of the whole group” (1938, p. 54). These theoretical concepts suggest that people have a psychological need to feel accepted and to identify with others in social situations. However, research on students’ need for belonging in the school context suggests that many schools unknowingly neglect or undermine fostering and facilitating this feeling of community (Osterman, 2009). DBP offers a way to build upon and incorporate a sense of belonging or ensemble among teachers and learners in the classroom that is vital to student success.

The teacher peers through the bottom of the bag at the students. An audible gasp is heard in the room. “Hmm...now, what if I tell you that someone cut a hole in this bag to help them solve a problem. What sort of problem can be solved by using a bag with a hole in the bottom?”

Imagination: During DBP, students are often invited to make new meaning based on what they know about and see within a situation. Although often associated with arts, the importance of imagination was widely championed by Russian psychologist and educational scholar Lev Vygotsky, who wrote about the relationship between student culture and context within education. Vygotsky suggests that when young people use their imaginations, they live beyond themselves (Vygotsky, 2004). It is the enactment of imagination in learning—as the young person engages with a character, a story, or a concept—that builds an understanding of alternative perspectives and ideas. Using the imagination is rigorous intellectual work, which occurs when two or more ideas are combined to form new images or actions that are not already in the young person’s consciousness (Vygotsky, 2004). Imagination is not simply about conjuring something out of nothing, or accessing creativity from within, but rather involves young people making sense of what is in front of them (Lee, Enciso, & Austin Theatre Alliance, 2017).

It gives the teacher real, tangible activities that they can do to move students to move toward higher order thinking, to get the rigor in the classroom.

—Fine Arts Director, Texas

—Fine Arts Director, Texas

When people imagine, they fill in the gap between what they know and what they think is possible. Rather than just working in the “as is” world within the classroom, in DBP, participants have the opportunity to bring the “as is” world into the “as if” (Heathcote & Bolton, 1995) creating and recreating and imagining and reimagining the world of the classroom and the world of the story (Edmiston, 2014). Many drama practitioners refer to imagination as a “suspension of disbelief,” suggesting that we can transform a chair into a throne or a desk into a mighty ship by agreeing to imagine together in and through the story. Galvin Bolton and Dorothy Heathcote, experts in drama and education, describe imagination as “‘raising the curtain’ inviting the class to take a peep at the metaphorical stage where fiction can take place” (1995, p. 27). In this fictional space in DBP, students “harness the power they have […] to direct, decide, and function,” (p. 18) thus becoming more responsible and agentic in what they learn.

The students freeze their bodies showing fear, bravery, and cunning.

Embodiment: In DBP, students often demonstrate their real or imagined viewpoints through their body. Drama is inherently an embodied practice, a production of cultural experiences and social interactions (Nicholson, 2005) that are placed and enacted in and by the body. In other words, people perform their own cultural and social identity as means to express who they are becoming. Additionally, embodiment in drama is also a way of showing what is known about concepts or ideas that may be better described through a physical representation. As drama and educational scholars Perry and Medina suggest, “The experiential body is both a representation of self (a ‘text’) as well as a mode of creation in progress (a ‘tool’)” (2011, p. 63).

Reflecting on twentieth century US classrooms, John Dewey wrote, “The limitation that was put upon outward action by the fixed arrangements of the typical traditional schoolroom, with its fixed rows of desks and […] pupils who were permitted to move only at certain fixed signals, put a great restriction upon intellectual and moral freedom,” (1938, p. 61). The idea of “fixed” education is still, at times, present in the United States—desks in rows oriented toward the teacher and bells indicating a passage in time. Social activist and educational practitioner Paulo Freire suggests that without activity and social interactions, it may be easy for teachers to see students as “empty vessels” to be filled with knowledge (1970). This perpetuates the idea of a mind/body dualism and disconnection where teachers are expected to solely address the needs of a child’s mind. However, as Vygotsky notes, every child in school “always has a previous history” (1978, p. 84), including cultural experiences that can be incorporated into teaching and learning in the classroom. Through the use of embodiment, DBP opens up an opportunity for students and teachers to show who they are and demonstrate their understanding.

Drama allows those boys a chance to use muscles and learn in a manner that is friendly to males and expressive in action, not just words. Look at Athabascan dancing, in which boys tell stories through kinesthetic movement. [DBP] helps connect schools to boys in a way that is expressive of their culture by allowing and praising movement to tell a story.

—Elementary Teacher, Alaska

—Elementary Teacher, Alaska

“So, how do we think this young girl on the cover of our book is feeling right now?” The teacher takes answers from students and invites them to build upon each other's ideas. “Thank you for your creative thinking. In our drama work today, we will explore how a young person can overcome great challenges. Let's meet the princess, now, and begin.”

Narrative/Story: In DBP, the teacher supports students to work together, using their imagination and bodies to take action within a story. The skill for creating narratives has been assumed to be a natur...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Part I: Why Use DBP?

- Part II: What Is DBP?

- Part III: How Is DBP Used?

- Epilogue

- Appendices

- Index