![]()

PART I

JOURNEYS

![]()

Introduction

On the Threshold of Liberty

The current amazement that the things we are

experiencing are “still” possible . . . is not philosophical.

This amazement is not the beginning of knowledge—

unless it is the knowledge that the view of history which

gives rise to it is untenable.

—Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History” in Illuminations

Safe Ports

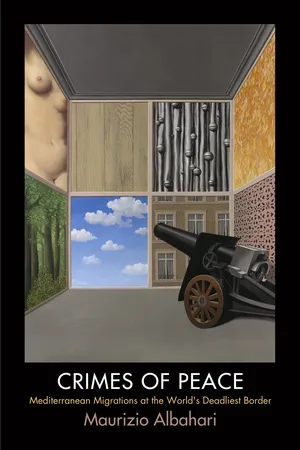

The cannon is surrounded by a variety of intricate fences. It aims at the bare torso, or perhaps at the bluish horizon beyond the steel bars, the wide-open window, and the raging flames. Agents, rescuers, and hesitant bystanders might be peeking through the airy curtains. Observers are haunted by preemptive angst.

René Magritte’s surrealist painting On the Threshold of Liberty (1929) uncannily foreshadows recurrent anxieties over security, rights, and democracy. Its eerie suspense resonates with the condition of maritime migrants skirting the edge of the abyss. Set in the vicinity of an Italian port, in 2014, the painting’s window would be open onto a procession of gray warships. They are directed to Augusta, Pozzallo, Catania, Porto Empedocle, Trapani, Ragusa, and Palermo, in Sicily; to Brindisi, Taranto, Crotone, Salerno, and Naples, on the southern Italian coast. On the warships’ decks stand Italian navy sailors, police agents, doctors, and Red Cross staff wearing paper-thin, white-hooded overalls, gloves, and surgical masks. Agents carry their batons, and a gun strapped to their legs. People in their charge sit on the deck in orderly fashion. Most also wear masks. Some women wear a veil and sunglasses; others show sunburned faces. Small children are nursing; older ones look with curiosity toward the city lights. Several teenagers are alone. Among them, some are pioneers, buying into a better future for the families they left behind. Others have been sent to safety by their distressed parents. Still others hope to reunite with families in northern Europe, or have become orphans. A man holds a baby intent on grabbing his glasses. Others have nothing and no one. Their eyes speak of excruciating exploitation and of physical distress. Everyone is sitting with their backs turned to the white blankets, barely covering the bodies of those who could not be rescued in time. As they climb down the boarding ladder, debilitated passengers are patiently assisted by navy sailors. Some have numbers stapled on their shirt. Wheelchairs and ambulances are waiting. The police prefect and the mayor are busy on their cell phones, as they allocate new arrivals into local facilities. Catholic clergy and local volunteer residents are also busy with preparations—hospitality will need to be extended.

On the outskirts of Tripoli, the smugglers Abdel, Tesfay,1 and the rest of their transnational syndicate are busy with a new endeavor. The black dinghy, manufactured in China, needs to be taken out of the sand, where it is kept hidden. Dollars will need to be counted, at the end of the day. Guns will be kept at arm’s reach. Regional militias, transnational terrorist groups, and governmental forces vie for power. Farther to the west they clash for the control of the Mellitah refinery and of the Greenstream submarine gas pipeline to Italy. They make unstable Libya decidedly unsafe for everyone, from Sabratha to Benghazi. They add to the vulnerability of displaced nonnationals, and engender postcolonial, economic, and national security preoccupations of Italian institutional partners.2 Far from southern Italy, on the twenty-third floor of a postmodern building in Warsaw, European Union (EU) border (Frontex) agents busily keep track of all the green dots on their flat screens.3 Each dot represents a group of migrants. The green dots “are small and sparse” between the coast of West Africa and the Canary Islands. They become “more dense” between Turkey and Greece, in the Aegean Sea. The maritime route between Libya and Italy,4 Africa and Europe, “is almost entirely green.” Frontex agents observe with disquiet the insurgency of such “risk regions” and “storm on the borders.”5 For each dot is the messenger of a breach in the EU’s preemptive approach to the containment of unregulated migration. From its command center in Rome, not far from the famous Cinecittà movie studios, the Italian state police is overseeing the arrival of the navy warship in the southern port. Huge flat screens visualize in real time the Mediterranean basin and the alerts launched by overcrowded migrant boats, the coast guard, armed forces, or commercial vessels spotting boats in distress. Here, the dots are red. This police facility is networked with Warsaw’s Frontex headquarters, thus contributing to the infrastructure of Eurosur, the technological platform intended to fight cross-border crime and possibly save lives at sea.6 From this fifth-floor room, the Italian police also coordinates the deployment of several Italian navy vessels, including two submarines, and a police plane. This constitutes the bulk of what the Italian government has termed the “military-humanitarian mission ‘Mare Nostrum.’ ” Critics in Italy and the EU disparage it as a state-owned ferry line for unauthorized immigrants and as an insurance policy for traffickers. Supporters hail it as a systematic search-and-rescue endeavor with a scope unprecedented in world history.

The 2011 Arab (Spring) Uprisings have dethroned Europe’s emigration gatekeepers in Egypt, Tunisia, and Libya (Chapters 2 and 5). The Iron Curtain, long blocking the gaze and the movement of most Europeans, seems to be a distant memory (Chapter 1). And yet the Mediterranean continues to be a trafficked, heavily militarized, and perilous maritime frontier (Chapters 2, 3, and 5). Adding to traditional layers of anti-immigrant political rhetoric and of gendered labor exploitation,7 in austere Europe a mood of global apprehension is coalescing around the arrival of Ebola8 and the looming proximity of “Islamic State” terrorists. Dust, debris, and a toxic smoke that never settles weigh on the daily existence of people in the Gaza Strip, in northern Iraq, in Libya, in Egypt, in Somalia, in Nigeria, in Mali, in the Central African Republic, in Eritrea, and in Syria.9

Since its inception in mid-October 2013, following two major shipwrecks (Chapter 5), Mare Nostrum has enabled many migrants in the central Mediterranean to survive the maritime leg of their journey. In eleven months of activity, vessels participating in the operation have brought to safety in Italian ports about 142,000 persons.10 Almost every one of them has been helped to transship to a navy vessel, a most difficult procedure, while at sea between Libya (or more rarely Egypt) and Sicily. For the most part, migrants in this stretch of the Mediterranean originate from Syria and Eritrea, followed by citizens of Mali, Nigeria, Gambia, Somalia, Pakistan, Senegal, and Egypt. At least 25,500 people are known to have died trying to reach Europe since 2000.11 In the first nine months of 2014, at least 3,072 people died or were missing in the Mediterranean, making 2014 the deadliest year on record.12 Crimes of Peace traces this record.

Back in the southern Italian port, volunteers are blowing soap bubbles, if only to give children a moment of distraction. The scirocco, the southeasterly Mediterranean wind—sirocco, shlūq, xlokk, jugo, ghibli—makes your face sticky. Locals will tell you in dialect, “lu sciaroccu te trase intra ll’ossa,” it gets everywhere, it corrodes baroque buildings and one’s bones. Today it brings seawater droplets right onto the news camera’s lens. Haze dampens my faux-Moleskine notepad.

Ali’s Journey

Ali is a Hazara Afghan now in his late twenties. His journey began in 1995. One of eight siblings, he left Afghanistan when he was ten, ready to face the risks of a perilous and expensive journey, rather than the certainty of coerced Taliban recruitment. One leaves, he explains, not only because one suffers, but because of seeing others suffering. He worked for three years in Iran, where “nobody ever asks who you are.”13 After he paid $2,500, smugglers helped him cross into Turkey, walking for ten days on difficult mountainous terrain, on the same snowy paths routinely taken by thousands of people from Tehran, Baghdad, and Kabul. Some get lost; others lose limbs to the cold. Ali worked in Turkey for two and a half years in conditions “worse than in Iran,” with neither identification documents nor the recognition of his refugee condition. Heavy patrolling made venturing alone across the land border with Greece impossible. Markets in Izmir and western Anatolia display a variety of life vests, targeting the hundreds of people intent on reaching Greece. Ali crossed into Greece on a speedboat, but was beaten and sent back to Turkey. In a second attempt, again the police at a Greek port caught and beat him, sending him back. Ali did make it to Greece the third time, sneaking onto a ferry by hiding in a commercial truck. One of his fellow travelers died of asphyxiation. Often, others attempting to cross this way are crushed by the freight. Like them, Ali did not fear death, but rather being discovered by the truck driver or the police. In Greece, he worked in the fields for a year and a half. After several failed attempts, in the port of Patras he hid himself under the air spoiler of a truck without the driver noticing. He made it by ferry to “an Italian port,” which he later understood was Bari, on the southeastern coast. When the carabinieri (army police force) found him, it was impossible to communicate. Though he could speak English, no agent was able or willing to listen to the story of a journey that took eight years.

Figure 1. Fragments in the “boats’ cemetery,” Lampedusa. Fishermen’s inscriptions often invoke God’s protection, shelter, and salvation. Photo: Maurizio Albahari.

In the Adriatic ports of Bari, Brindisi, Ancona, and Venice, many Afghan teenagers like Ali might not even be allowed out of the ship’s hold. Along with fellow stowaways, including Syrians, Somalis, Iranians, Pakistanis, and Kurds, they are summarily returned to Patras or Igoumenitsa in Greece.14 Often they are not interviewed individually, nor given the opportunity to apply for asylum in Italy.15 The decision is not made by an asylum committee, but by border police or finance guard16 agents. To the officials’ discretionary gaze, some of these teenagers don’t look like minors. Alternatively, the “truth” is expected to emerge “from their body,” to quote Fassin and D’Halluin’s work with refugees in France (2005).17 Their left-hand bones might or might not be the bones of a minor—x-ray screenings and mathematical algorithms speak on these travelers’ behalf.18 To use the institutional vocabulary, agents may “reject” them from the national territory and, without any written document, “entrust” them to the ferries’ captains for their “readmission” journey to Greece, often locked in the hold’s baggage compartment.19 These migrants go back to a struggling life on the geographic and socioeconomic margins of austere Greek cities.20 There, they might be targeted by local supremacist groups—with exclusionary discourses and with makeshift bombs. One October morning in 2008, hundreds of asylum seekers were lining up outside Athens’s Central Police Asylum Department. Intent on preserving public order, the police used force and charged them. One person was killed and several others injured by agents of the state precisely as they were trying to ask that state to protect them.21 When, conversely, they are allowed to lodge an application in Greece, it is virtually certain they will be unable to obtain asylum.22

In Greece, as in Italy, these migrants are also aware they will not be able to legally travel to other EU countries to apply for asylum. With very few exceptions,23 EU Regulation No. 604/2013, known as Dublin III Regulation,24 suggests that the country where non-EU persons first enter the EU is responsible for accepting and examining their asylum applications—which makes Malta, Cyprus, and Greek islands including Crete less than ideal first destinations. Having survived the perils of a westward journey taking years, severely indebted, and keen on reaching friends or families elsewhere in Europe, they do not have the option of going “back home” either, even when home is a safe place. They again travel to the port cities, hoping to reach Italy. Greece, like Italy, is considered a “doorstep of Europe” (Cabot 2014), a stage in refugees’ journey toward northern European destinations such as Sweden, Germany, and the Netherlands. These countries feature more established ethnic communities, better legal provisions, and a more promising reception. During 2013, some 398,200 asylum applications were filed in the twenty-eight EU countries, including 109,600 in Germany, 60,100 in France, 54,300 in Sweden, and 27,800 in Italy.25 Using such figures, several European leaders have voiced their concern regarding the Mare Nostrum mission.26 Leaders use the standard, somewhat abstract vocabulary of sovereignty and human rights. Bavarian interior minister Joachim Herrmann, a Christian conservative, publicly alleged that the Italian police is not implementing the Dublin Regulation: “Italy in many cases intentionally does not take personal data and fingerprints from refugees to enable them to seek asylum in another country.” There were no comments from the Interior Ministry in Rome, in charge of “law and order” in the country, except that “the remarks were made by a regional [Bavarian] minister, not a German government minister.”27 But Germany’s turn is soon to come. German interior minister Thomas de Mazière, also a conservative, observed that “it’s clear to all European ministers that the justified and responsible campaign by the Italians has become a ‘pull factor,’ as we call it.”28 Socialist Bernard Cazeneuve, French minister of the interior, asserted that “member states need to regain control of the EU’s external borders, better implement asylum procedures, and step up efforts to dismantle human smuggling networks.”29 Between January and July 2014, French authorities denied entry to some 3,411 clandestins (unauthorized immigrants), including Eritrean and Syrian nationals, transiting from Italy.30 Austrian guards, too, discretionally enforce the otherwise “open” Schengen border31 and, during the summer months of 2014, denied entry to some 2,100 non-EU “foreigners” transiting from Italy.32

In the first seven months of 2014, some 17,700 minors were registered as arriving in Italy, including 9,700 unaccompanied—especially from Eritrea, Egypt, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan.33 Many of them flee the facilities charged with their protection, notably in the absence of information about their legal rights and when enticed by friends, extended family, or trafficking networks.34

But Ali was “lucky,” as he puts it. From the port, he was taken to one of the immigration reception facilities in southern Italy and, soon after, to an orphanage. He applied for political asylum and was told he would get “an answer” in approximately six months. He was recognized as a political refugee after two years. Ali has been living in a small southern Italian town, where I have often met him over a decade, counting on t...