![]()

1

Activism

Guobin Yang

First published in 1976, Raymond Williams’s Keywords captures the spirit of his times. The 110 entries in the first edition include radical, revolution, and violence. Liberation is one of the 21 entries added to the second edition in 1983. These words linked together the worldwide revolutionary movements of the 1960s and early 1970s.

From the vantage point of the twenty-first century, however, the absence of the word activism in Williams’s classic is conspicuous. In the decades since its first publication, but especially since the 1990s, activism has become a popular word in contemporary cultural and political discourse. It is used not only by citizens and civil society organizations, but also by government bureaucracies, international agencies, and even business corporations. Furthermore, the growing popularity of activism is accompanied by the declining use of revolution and liberation, or at least declining up until the “Occupy” movement and the Arab Spring protests. What does the ascendance of activism reveal about contemporary culture, society, and politics?

An Ambiguous Word

Activism is an ambiguous word. It can mean both radical, revolutionary action and nonrevolutionary, community action; action in the service of the nation-state and in opposition to it. This ambiguity has existed since its first usages in the early twentieth century. The German philosopher Rudolf Eucken used the term in his 1907 book The Fundamentals of a New Philosophy of Life to refer to “the theory or belief that truth is arrived at through action or active striving after the spiritual life” (OED, 3rd ed.). In continental Europe during World War I, activism meant “advocacy of a policy of supporting Germany in the war; pro-German feeling or activity” (OED, 3rd ed.). The word in 1920 began to take on the more general meaning of “the policy of active participation or engagement in a particular sphere of activity; spec. the use of vigorous campaigning to bring about political or social change.” By 1960 the term could have an almost incendiary connotation, as in “The sizzling flame of activism is visible in both the agricultural and pastoral districts” (OED, 3rd ed.). About activism as a service to the nation-state, Hoofd (2008) writes:

Etymologically, ‘activism’ has strong affinities not only with an essentially transcendental philosophy of life, but also with nationalism and industrialization. Indeed, it appears that ‘activism’ was an economic strategy originally employed for the benefit of the nation-state in which its citizens could enjoy the largest amount of ‘spiritual freedom’ through actively encouraged but closely monitored economic competition.

Activism thus had several different meanings in its history—a philosophical orientation to life, an economic strategy to mobilize citizens for national industrialization, a pro-German activity during World War I, and a vigorous political activity.

In its contemporary usage, activism generally refers to citizens’ political activities ranging from high-cost, high-risk protests and revolutionary movements (McAdam 1986) to everyday practices aimed at protecting the environment (Almanzar, Sullivan-Catlin, and Deane 1998) and to corporatized NGO activism (Spade 2011). Its popularity undoubtedly has something to do with its multiple, ambiguous meanings, which make the word suitable for different purposes.

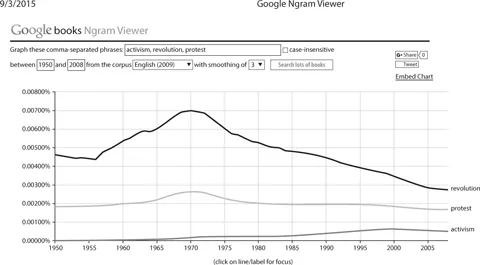

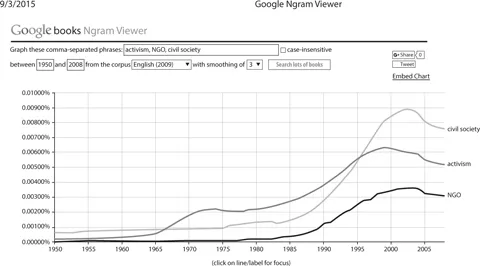

Over the past thirty years, activism has also become less likely to mean radical and revolutionary action and more likely to mean moderate civic action. Many social movements and activism studies support this hypothesis (Meyer and Tarrow 1998; Samson et al. 2005; Spade 2011). A glance at the frequency of the term and its associated words also helps: consider Google Ngram Viewer, which contains 5.2 million scanned books published between 1550 and 2008, with 500 billion words in total and 361 billion in English (Michel et al. 2010). As a hypothesis, suppose that a stronger association of activism with revolution or protest rather than NGO or civil society implies a more radical connotation, whereas a declining association with terms like revolution may indicate a less radical connotation. Now observe in figures 1 and 2 the patterns of usage in Google Ngram Viewer for activism in comparison with revolution and protest and with NGO and civil society from 1950 to 2008.

Figure 1 shows that the use of revolution declined steadily after the 1970s in proportion with the rising frequency of activism, with protest holding relatively steady. Figure 2 shows a remarkable parallel rise in the use of activism, NGO, and civil society. If NGO and civil society activism tends to be moderate, institutionalized, and even corporatized (Samson et al. 2005; Spade 2011; Dauvergne and LeBaron 2014), rather than radical and revolutionary, then the usage patterns suggest that from 1950 to 2008, especially after the 1990s, activism has mellowed to indicate moderate rather than radical forms of action.

Figure 1. Use of activism, revolution, and protest in Google Ngram Viewer, 1950–2008.

Figure 2. Use of activism, NGO, and civil society in Google Ngram Viewer, 1950–2008.

An Ambivalent Age

The ambiguity of the increasingly popular keyword appears to serve well the politics and purposes in the current age of ambivalence. That ambivalence is a condition of modernity is already a thesis well developed in the works of classic social theorists from Marx to Weber (Smart 1999), although the post-1989, post–Cold War world entered a period of “new ambivalence” (Beck 1997). This “new ambivalence” rests on the unmooring of traditions and traditional communities, the breakdown of old boundaries of the public and the private, the collapse of faith in human progress, the retreat of grand, emancipatory politics and the rise of life politics, and what Beck calls the “reversal of politics and non-politics” where “the political becomes non-political and the non-political political” (Beck 1992: 186). The causes for this upheavel include, in brief, the shift from industrialization to postindustrialization in global economies, the crisis of the nation-state under the onslaught of globalization, the diffusion of new forms and patterns of communication associated with the development of internet and mobile technologies, and, over and above all these, the disembedding of institutions and the advent of a society of risk (Giddens 1990; Beck 1992). In essence, as Beck puts it, this new ambivalence is the consequence of the “gradual or eruptive collapse of previously applicable basic certainties” for practically all fields of social activity (Beck 1997, 11).

These influences express themselves in political participation complexly. On the one hand, aspirations for political struggle continue to take both radical and nonradical forms. The Zapatista revolt and the protests against the World Trade Organization (WTO) in Seattle in the 1990s, for example, were radical eruptions—as were the more recent Occupy Wall Street and Arab Spring protests. On the other hand, the history of activism and protest since the 1990s remains marked more by moderation than by radicalism in both Western democracies and other countries.

In Western democracies, popular political radicalism declined in the wake of the protest cycle of the 1960s and 1970s. What have appeared instead are “social movement societies,” where protest becomes increasingly institutionalized and bureaucratized, and “civic” rather than disruptive. Meyer and Tarrow (1998, 20), editors of the volume The Social Movement Society, write, “Although disruption appears to be the most effective political tool of the disadvantaged, the majority of episodes of movement activity we see today disrupt few routines.” A study of over four thousand events in the Chicago area from 1970 to 2000 finds that “sixties-style” protest declined, while hybrid events combining public claims making with civic forms of behavior increased (Samson et al. 2005). The most distinctive pattern of the post-1970s landscape of citizen participation is collective civic action, not disruptive action (see participation).

In China and the former Soviet bloc, large-scale protest activities declined after the “Velvet Revolution” and the Tiananmen student protests in 1989. History was proclaimed to have ended and revolution a relic of the past. In the wake of the Tiananmen protests, even Chinese intellectuals who had supported the Tiananmen movement bid “farewell to revolution,” advocating instead reform as a method of political change and a prominent practice since the 1990s (Li and Liu 1995). Deradicalized civic action, such as NGO activism, also became more common than radical protest as revolutionary aspirations gave way to reformist agendas (Yang 2009).

Of course, moderation does not capture all the ambivalent trends of contemporary activism, such as the rise of the outsourcing of grassroots politics (Fisher 2006), the “nonprofitization” of social movements (Spade 2011, 40), and the corporatization of activism (Dauvergne and LeBaron 2014). Some activist organizations outsource their political campaigns to commercial campaign organizations, much as big corporations outsource their jobs and products to overseas factories. Others collaborate with businesses in pursuit of dubious goals, as when environmental organizations partner with oil companies to protect the environment. Deeply troubling to critics, “activist organizations have increasingly come to look, think, and act like corporations” in the last two decades (Dauvergne and LeBaron 2014, 1).

The Internet Brings Hope

At the same time the internet has introduced a range of new practices known as cyberactivism, hacktivism, internet ac...