![]()

1

Early Precedents

THE first government intervention in New York City housing design occurred within a year of the arrival of the first colonists in 1624. The Dutch West India Company devised a set of detailed rules regarding the types and location of houses that could be built in their new colony.1 The rules proved impractical, however, and had to be abandoned. But as the city grew, laws were passed almost on a yearly basis, mandating one or another aspect of building and sanitation standards. Major advances were made less frequently, many times only after some major disaster.2 The government was involved with housing first at the municipal and provincial levels, and only later at the state level. During the first two centuries of New York City’s history, building law was concerned primarily with the prevention of fire and disease.

The first comprehensive construction law for fire prevention was enacted in 1648. This law forced the removal of wooden and plaster chimneys to eliminate fire hazards.3 The city’s fire laws were strengthened in 1683 when “viewers and searchers of chimneys and fire hearths” were appointed to report violations.4 In 1775 drastic measures were approved which marked the beginning of the modern period in legislation against fire. The new law provided both for the prevention of fires and for controlling them once they started. Its provisions dealt with both new construction and the improvement of buildings already built.5 The legislation was passed only a year before approximately one-quarter of the city was destroyed by fire and had to be rebuilt.6 The use of fire walls was made mandatory by the New York state legislature in 1791. All adjoining buildings of three or more stories were required to be constructed of masonry party walls, with parapets at the roofs to prevent fire from jumping to adjacent buildings.7

The earliest comprehensive law covering hygiene was passed by the Council of New Netherland in 1657 prohibiting the disposal of rubbish and filth into the canals.8 Until the turn of the nineteenth century, sanitary legislation remained concerned primarily with sewage and trash disposal. Some limited attention was also given to separating incompatible land uses and controlling the grazing of cattle, horses, and hogs. In 1695 the Provincial Legislature authorized the Common Council to appoint five “Overseers of the Poor and Public Works and Buildings” with the authority to impose a tax for relief to the poor and for public sanitation services.9

The eighteenth century began with a smallpox epidemic in 1702 that killed five hundred persons. Throughout the century, epidemics became more and more commonplace. By the end of the century, the New York City water supply was quite polluted. The yellow fever epidemics in the 1790s led to the first detailed and relatively objective reports on the sanitary conditions of the city.10 In 1797 the New York state legislature appointed three commissioners of health for New York City who were given the power to make and enforce regulations regarding sanitation.11 They constituted the first Board of Health. Also around this time, the city began to build sewers, and small sections of the city were supplied with running water. The first gaslight company was incorporated in 1823, offering an alternative to the hazards of the oil lamp and coal fire.12 In 1835 the construction of an aqueduct from the Croton River forty miles north of the city was approved by public vote. By 1842 the cold and pure waters of the Croton Aqueduct were flowing to the city, providing the basis for a much-needed modern water distribution system.13 Even as late as 1827, one of the major public sources of potable water had been the ancient “tea water pump” on Park Row.14 Simultaneous with these technological improvements, however was the critical worsening of fire and hygienic conditions.

Between 1800 and 1810 the population of the city jumped from 60,515 to 96,373,15 accompanied by great epidemics and social turbulence. The yellow fever epidemic of 1805 alone was estimated to have caused the death or illness of at least 645 persons.16 During this decade the Board of Health was forced to define in greater and greater detail hygienic standards for the public. The laws began to reflect a naive understanding that the problems of health required measures that went beyond simple cleanliness. For example, hygienic concerns were related to population density in a law regulating lodging houses passed by the Common Council in 1804.17 It was the first legislation to specify maximum densities for housing.

The first mandate for “professional” intervention in housing design came in 1806, when a Board of Health report suggested the hiring of a “scientific and skillful engineer” to assist builders.18 A consciousness of the need for slum removal became more intense during this period, although there were many historical precedents for such activity. As early as 1676 the Common Council approved the right of the city to take control of abandoned and decayed houses, and to turn them over to new owners who were willing to fix them up or rebuild.19 In 1800 the New York state legislature granted power to the city to purchase property within designated areas that violated building regulations. These parcels could then be disposed of in a manner as “will best conduce to the health and welfare of the said city.”20 Within the next several decades, the law was applied in various situations, usually to abandoned buildings. There were some important exceptions, however. In 1829 the law was used to raze four houses occupied by black families;21 in 1835 condemned buildings at Christopher and Grove streets were replaced by a public park.22

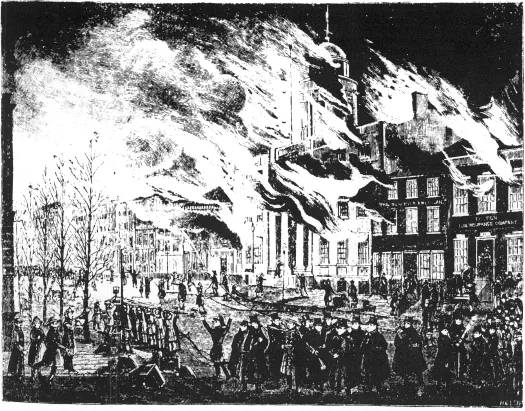

Figure 1.1. Scene from the Great Fire of 1835, the largest in the history of New York City, and an important influence on building legislation in the following decades.

Major fires occurred in 1811, 1828, 1835, and 1845. Major epidemics of yellow fever and cholera occurred in 1819,1822,1823,1832,1834, and 1849. Minor crises arose almost every year. Reports and proposals proliferated, and they became the theoretical basis for preventive action. In a report on the cholera epidemic of 1819 written by Dr. Richard Pennell in 1820, the link between housing form and health was definitively established. Pennell compared the number of stricken residents who lived in cellars with the number who lived above cellars. In one comparison, he found that “out of 48 blacks, living in ten cellars, 33 were sick, of whom 14 died; while out of 120 whites living immediately over their heads in the apartments of the same house, not one even had the fever.”23

Comprehensive legislation related to health was extremely slow to develop, partially because of moral and ethical issues. The worst cholera epidemics were in 1832, 1849, and 1866. The Metropolitan Board of Health was legislated in 1866, and thereafter, health measures had reached a degree of preventative measure such that no further massive outbreaks occurred.24 The problem of fire was easier to legislate, although here, also, response was remarkably slow. The great fire of 1835, the worst in the history of the city, destroyed almost every building south of Wall Street and east of Broad Street—a total of 674 buildings valued at $26 million (figure l.l).25 Ten years later a last great fire occurred that was almost as destructive. But it was not until even later, in 1849, that the Common Council upgraded the fireproofing laws of the city to reasonable standards.26

Between 1820 and 1860 the population of the city grew from 123,706 to 813,699 persons, with another 266,661 persons living in Brooklyn.27 The introduction of steam navigation on the Atlantic caused large increases in immigration toward the end of this period. Between 1820 and 1860 4 million immigrants reached the United States, most through New York City. By 1860 383,717 immigrants had settled in the city.28 By mid-century New York had achieved its position as the North American metropolis.29 During this time the dominant characteristics of the city’s present-day culture of housing began to emerge; New York became a city not of “houses,” but of “housing.” A growing proportion of its inhabitants lived in collective accommodation that was unique in the nation. This condition crossed class lines from the tenements of the poor to the increasingly dense row housing of the upper middle class. Most fundamentally, the increased physical congestion was substantially altering both the house form and the culture of the colonial city. In 1847 a famous observer of the New York scene, Philip Hone, remarked that New York was appropriating certain characteristics of metropolitan Europe in the complexity of its outlook: “Our good city of New York has already arrived at the state of society found in the large cities of Europe; overburdened with population, and where the two extremes of costly luxury in living…are presented in daily and hourly contrast with squalid misery and destitution.”30

Until the mid-nineteenth century, those aspects of fire and sanitation legislation that affected the poor were perhaps not intended as much to improve the condition of the poor as to protect the rich from the scourages of poverty. Laws were passed to control fire and disease because these were not easily contained within the area of origin, and on the occasion of calamity both rich and poor suffered. Improvement of the living conditions of the poor was in the immediate self-interest of the rich. But as the city grew and ghettos developed, the rich could put more distance between themselves and the poor. Legislation began to reflect more abstract ideas of social control.

By 1850 some new notions of the possible relationship between housing and social control had developed around the concept of private “philanthrophy.” The extensive writings of Dr. John H. Griscom, who served as city inspector in 1842 and became one of New York City’s first crusaders for housing reform, represent the first comprehensive treatment of the subject.31 He appears to have been greatly influenced by the work in England of Sir Edwin Chadwick.32 Writing in 1842 about the difficulties of enforcing housing standards for the poor, Griscom identified the landlords as having the resources and responsibility to improve housing conditions. Because he could find no sound economic reasons within the capitalist system for landlords to pursue such improvements beyond the minimums set by law, he was forced to call on their goodwill. His arguments implied that for all concerned, good intentions would be more profitable than exploitation. The landlords would be duly compensated with “the increased happiness, health, morals and comfort of the inmates, and good order of society, which cannot be estimated in money.”33

Griscom ...