The Emerging Markets Century

How a New Breed of World-Class Companies Is Overtaking the World

- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The Emerging Markets Century

How a New Breed of World-Class Companies Is Overtaking the World

About this book

A new breed of powerhouse companies from the emerging markets is catching their Western competitors off-guard. Household names of today - IBM, Ford, Wal-Mart - are in danger of becoming has-beens as these more innovative superstars rise to dominance, representing both an urgent competitive challenge and an unprecedented investment and business opportunity. Understanding how they have become world-class market leaders - and where they are going next - is crucial to an understanding of the future of globalization. Training his brilliant investor's eye on the top twenty-five of these emerging market companies, visionary international investment analyst Antoine van Agtmael takes readers into the boardroom suites and labs where they are outmanoeuvring their Western competitors. He reveals how these companies have made it to the top of the global heap, profiling major players such as China's Haier appliance manufacturer; Korea's Samsung; Brazil's Embraer jet maker; and India's Infosys. Divulging their strategies for future growth, he analyses how their rise to prominence will change our lives. His unique insights reveal both how we in the West can capitalize on the opportunities these companies represent while also mobilizing a powerful response to the challenges they present.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Part I

Globalization

has No Borders

Chapter 1

Who’s Next?

How emerging multinationals you’ve never heard of could eat your lunch, take your job, or possibly be your next business partner or employer

the-art handhelds and smart phones for the likes of Verizon, Vodafone, Palm, and HP. All around me were young, smart, ambitious engineers from Taiwan and China, hard at work testing everything from sound in a sophisticated acoustics studio to new antennas, drop impact, and the scratch resistance of new synthetic materials. Designed in Taiwan, these high-tech video phones would shortly be mass produced, and one day soon sold around the world.

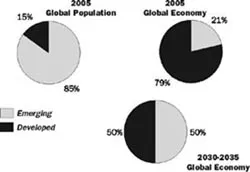

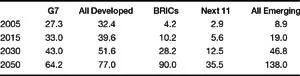

The Emerging Markets Century

The Rise of BRICS and other Emerging Markets

in the Global Economy (In Trillions)

- Korean Samsung’s powerful global brand is now better recognized than Sony’s, its R&D budget is larger than Intel’s and its 2005 profits were higher than those of Dell, Nokia, Motorola, Philips, or Matsushita.

- The regional jets we fly are made by Embraer in Brazil.

- Mexico’s CEMEX has become the largest cement company in the United States, the second largest in the UK, the third largest globally, and the leader in many other markets.

- Computers are now not just made but largely designed in Taiwan and China.

- We get most of our advice about how to fix those computers from India.

- Russia’s Gazprom’s gas reserves are larger than those of all the oil majors combined and its market capitalization rivals that of Microsoft. Europe would freeze in the winter without its gas supplies, as was pointedly demonstrated when it briefly turned off the tap. Meanwhile, Russian Lukoil’s gas stations (bought from Getty Oil) can be found near the White House, the New York Stock Exchange, and all along the East Coast.

- Modelo, a Mexican company, sells more beer (Corona) to Americans than Heineken. And a Brazilian CEO became head of Inbev-Ambev, the world’s largest beer company, in a merger in which “old” European beer companies were amazed at the efficiency of their Brazilian partners.

The Invisible Champions

- Are widely recognized as leaders in their industry on a global, not just national or...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction: The Emergence of Emerging Markets

- Part I: Globalization has No Borders

- Chapter 1: Who’s Next?How emerging multinationals you’ve never heard of could eat your lunch, take your job, or possibly be your next business partner or employer

- Chapter 2: Against the OddsThe strategies that propelled twenty-five emerging multinationals into world-class corporations

- Part II: The New Breed: Twenty-Five World-Class Emerging Multinationals

- Chapter 3: From Under the Radar Screen: Building Emerging Global BrandsSamsung and Concha y Toro are setting new trends

- Chapter 4: Other Roads to Brand Leadership: Buy It or It May Drop in Your LapLenovo buys IBM ThinkPad, Haier tries to buy Maytag, and Corona Beer has its accidental iconic brand

- Chapter 5: China’s Largest Exporters…Are Taiwanese: Building a Global Presence Behind a Veil of AnonymityHon Hai and Yue Yuen make your computers, cell phones, and shoes

- Chapter 6: From Imitators to InnovatorsTaiwan’s TSMC and High Tech Computer win by reinventing industries and products

- Chapter 7: Your Next Global Employer?Hyundai and CEMEX want to be close to their customers everywhere

- Chapter 8: Turning the Outsourcing Model Upside DownBrazilian plane maker Embraer stays in the driver’s seat with suppliers in the developed world

- Chapter 9: Commodity Producers that Redefined their IndustriesAracruz, CVRD, and POSCO defied conventional wisdom…and the odds

- Chapter 10: Alternative Energy ProducersSouth Africa’s Sasol makes oil out of coal and gas, Brazil’s cars use biofuels, and Argentina’s Tenaris makes pipes seamless enough to be used deep under the ocean or in Arctic climates

- Chapter 11: The Revolution in Cheap BrainpowerIndia’s Infosys and Ranbaxy transform the worlds of software design and generics

- Chapter 12: New Global Media StarsMexico’s Televisa, India’s Bollywood, and Korea’s game makers appeal to worldwide audiences

- Part III: Turning Threats into Opportunities

- Chapter 13: A Creative ResponseDon’t be defensive or stick your head in the sand—develop new policies and strategies

- Part IV: An Investor’s Resource

- Chapter 14: Investing in the Emerging Markets Century: Ten RulesA long-time investor looks at pride and prejudice in emerging market investing

- Appendix: Financial Profiles of 25 World-Class Emerging Multinationals

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgments

- Index