Though “chocolate” is commonly referred to in a general sense, several distinctions should be made. Chocolate, itself, is the main processed byproduct of the cacao bean (or nib or cotyledon). Cacao, the species of the Theobroma cacao plant or “Chocolate Tree”, is typically used in reference to the tree or pod or bean, whereas cocoa is used in reference to the powder made from the processed bean. Additionally, “chocolate” has carried different names in different cultures. For example, “chocolate” in Spanish, Portuguese and English languages was known as chocotyl to the Aztecs and chocolatl to Mexican Americans. In the Old World, the French called it chocolat, the Italians cioccolata, and the Germans schokolade. Russian languages refer to it as shokoladno. Except when keeping faithful to other uses in quotations, we will simply refer to this product as “chocolate” throughout this book.1

Histories of chocolate typically recount chronological discoveries regarding cacao seed (bean) products and the sequential improvements through which cacao has become used as medicine.2 Among the earliest evidence for chocolate’s medical use are the remaining iconographic works and fragments of Olmec, Maya, Zapotec, Mixtec and Aztec Art. Additional records from these eras are provided in groups of writings preserved under such names as the Florentine and Tuleda Aztec Codices as well as the Dresden and Madrid Mayan Codices. In recent decades, new forms of evidence have been uncovered in the remnants of Theobroma cacao found in the pottery and crockery of the Mokaya of Mesoamerica dating back to 1900 BC.3

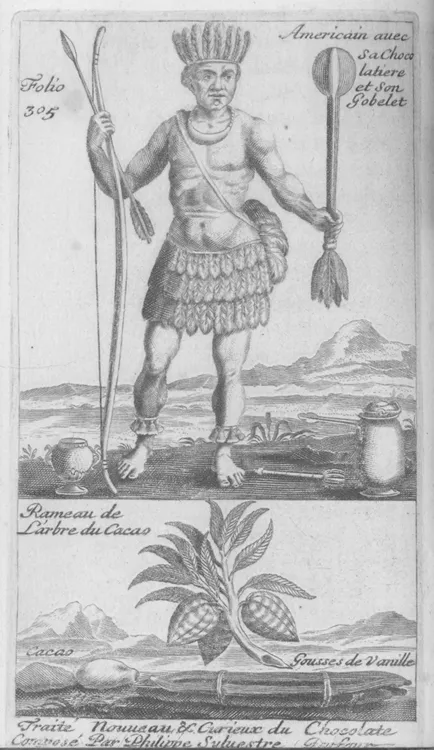

Throughout human history, the importance and relative weight of oral tradition has been paramount, and indeed, has been the means by which people in earlier times generally learned of chocolate’s potential health benefits. Various cultures speak of Quetzalcoatl as God of the air and, at least to the Aztecs, the patron saint of agriculture. On earth, this “Garden Prophet” lived in a beautiful sylvan grove where “students” of astronomy, medicine and agriculture would gather. It was there, so the story goes, that the special medicinal powers of the Chocolate Tree were discussed. The Aztec Emperor Moctezuma offered chocolate as his greatest gift to humankind as an apotheosis or glorification.4 Based upon hearsay about such cultural uses, Carl Linnaeus gave the scientific name Theobroma cacao to the plant that provided the essential ingredient to this favorite drink of the Gods (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 An Indigenous American Surrounded by a Chocolate Drinking Cup, a Molinet, and a Chocolate Pot, all atop an Image of the Cacao Pod. Frontispiece from Phillippe Sylvestre Dufour’s Traitez Nouveaux et Curieux du Café, du Thé et du Chocolat (1688).

(Courtesy of Hershey Community Archives, Hershey, Pennsylvania, USA).

Looking at other forms of evidence, such as biogeography, we find that is was not so much the gathering of substances but, conversely, their spread across regions that secured chocolate’s reputation. In this context, it was macaws and monkeys rather than Moctezuma who were responsible for naturally spreading the essence of cacao across a wide ecological area. By opening the cacao pods, devouring the luscious pulp, and leaving the bitter tasting beans where they dropped, it was these nonhumans who significantly expanded the terrain for future harvests. Though our primary focus is the human consumption and use of this natural product, we readily acknowledge this important nonhuman aspect of chocolate’s early natural history.

Scholars from myriad fields have come to appreciate the importance of seeking indigenous knowledge in order to better understand those cultures that, for quite some time, had been termed as “primitive” and the “other”. The Interinstitutional Consortium for Indigenous Knowledge (ICIK) at Penn State University in State College, Pennsylvania has become a leading program in academe that studies indigenous knowledge as a unique focus. According to ICIK, indigenous knowledge is

an emerging area of study that focuses on the ways of knowing, seeing, and thinking that are passed down orally from generation to generation, and which reflect thousands of years of experimentation and innovation in everything from agriculture, animal husbandry and child rearing practices to education; and from medicine to natural resource management. These ways of knowing are particularly important in the era of globalization, a time in which indigenous knowledge as intellectual property is taking new significance in the search for answers to many of the world’s most vexing problems – disease, famine, ethnic conflict, and poverty. Indigenous knowledge has value, not only for the culture in which it develops, but also for scientists and planners seeking solutions to community problems . . . . [including] health, agriculture, education, and the environment, both in developed and in developing countries.5

In terms of chocolate, “indigenous” refers to the equatorial Americas in the lowland forests of the Amazon–Orinoco basin flood plain. From there, colonisation boosted the cultivation of cacao beans into the realm of a major industry in tropical equatorial regions across the globe. Despite decades of dedicated interest in improving the harvest yield of cacao in these regions, chocolate’s indigenous history has only recently garnered significant academic interest. Best among these works is Cameron L. McNeil’s edited volume, Chocolate in Mesoamerica: A Cultural History of Cacao (2007). A complete indigenous history of chocolate as medicine in Mesoamerica awaits an author.

Work in this volume focuses upon history drawn from various types of evidence, ranging from tradition to testimonials to travel narratives as well as crockery, case studies and cookbooks. Covering more recent centuries, the power of advertising is analysed as another important source of surviving recorded evidence. The closing chapters focus more upon biomedical evidence. Still, as this work makes apparent, word-of-mouth (i.e., a type of oral tradition sharing indigenous knowledge) has never really diminished as a key source of evidence in promoting chocolate’s healing powers.

“Evidence” has become an increasingly important buzzword within the healing arts over the past few decades. For instance, this term appears in the subtitle of David Katz’s Nutrition in Clinical Practice: A Comprehensive Evidence-Based Manual for the Practitioner, a work which includes a chapter on the “Health Effects of Chocolate”. In many ways, keeping evidence as a central thread throughout our historical account has helped us retain a pertinent focus upon chocolate’s potential therapeutic effects. To better appreciate this historical thread when applied to chocolate, a brief reflection upon the growth and meaning of “evidence” used to support general biomedical and health claims over the past few centuries is warranted.

1.1 VALUING MEDICAL “EVIDENCE” IN THE PAST AND PRESENT

In our era, the therapeutic efficacy of medical practices and remedies has been recast within the mold of evidence-based medicine (EBM). Beginning in the early 1990s, the then newly established clinical discipline of EBM referred to the “conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients”.6 Clinical expertise is combined with newly supported biomedical evidence obtained through systematic literature searches to ensure the delivery of the highest quality health care. EBM also incorporates a “thoughtful identification and compassionate use of individual patients’ predicaments, rights and preferences in making clinical decisions about their care”.7 Including the patient in the decision-making process conforms with the late Cornell University internist, Eric Cassell’s notable directive that to effectively relieve suffering, physicians must be ever mindful of a patient’s entire personhood.8

Since the early 1990s, EBM has been adopted into medical school curricula, celebrated in medical manuals, deliberated in medical literature and featured at myriad medical conferences. The vast international consortium of clinicians and consumers known as the Cochrane Collaboration has provided systematic literature reviews as required by EBM methodology. Despite its popularity, arguments have surfaced claiming that EBM is either “old hat” or “impossible to practice”.9 At the heart of the matter lies the concern over acknowledging what has truly counted as “evidence” in different eras of medicine’s heritage.

Around the time when chocolate was first introduced into European culture, “evidence” was reexamined within scientific and medical contexts. Sir Francis Bacon, best known at the time for his financial prowess as Lord Chancellor under the reign of England’s James I, is credited with providing a new framework for science: the experimental method (Figure 1.2). If the purpose of science was, as he argued, to give humans mastery over nature, thereby extending both human knowledge and power, then the laws of nature must be better understood. Such understanding, so Bacon proclaimed in Novum Organum (1620), was attainable only after shifting scientific thought from deductive reasoning towards an inductive approach coupled with experimentation.

Figure 1.2 Sir Francis Bacon, from title page of David Mallet’s The Life of Francis Bacon, Lord Chancellor of England (1740).

Bacon’s inductive method of interpreting nature – which others later applied to chocolate – involved the assembly of a “sufficient, . . . accurate collection of instances”, or evidence, gathered “with sagacity and recorded with Impartial plainness”. After viewing it “in all possible lights, to be sure that no contradictory . . . [evidence] can be brought, some portion of useful truth”, general law, or hypothesis could then be established.10 He argued that natural philosophers who relied solely upon the authority of the past – which for all university graduates of his day was still the ancient logic (or Organon) of Aristotle – failed to advance any new understanding of nature. Bacon advocated the experimental method as the most reliable manner to free science from the “paralysing dependence of previous students of nature on the rough and ready conceptual equipment of everyday observation”.11

Like science, medicine had also long been practised according to ancient dogma. Hippocratic wisdom proffered guiding aphorisms of the medical art. Contrary to Aristotelian reasoning, Hippocratic diagnoses stemmed from developing a general hypothesis based upon carefully observing specific signs and symptoms. Yet according to Bacon, Hippocratic doctrine had become “more professed than labored” by the early 1600s. Subsequently, he queried how to ascertain which contemporary medical practices yielded the very best possible outcomes.

Bacon’s concerns regarding medical practice stemmed from observing how a theory-based approach had come to prevail over a (Hippocratic) patient-oriented one. Adding support to Bacon’s attempt to reinvigorate Hippocratic perspectives, one seventeenth-century practitioner, Thomas Sydenham – later dubbed the “English Hippocrates” – vehemently opposed theory-based medicine claiming, instead, that medicine should be practised by first objectively gathering signs and symptoms without prematurely speculating upon their significance. Then, only after distinguishing useful signs from red herrings could the true understanding of a disorder become realised. By restoring this Hippocratic inductively derived diagnosis, expected disease patterns could then be deduced. The London surgeon and physician, Daniel Turner echoed Sydenham in the following century, claiming that disease was not a priori predictable according natural laws. Physicians were not like natural philosophers who were free to apply rules “to Bodies inanimate, or putting simple Fluids into . . . Balance . . . [or] counting . . . . Pressures or Impulses”. Rather, they were dealing with human lives. Physicians, he asserted, must not “sacrific[e] Men’s Lives” for the sake of some “meer [sic] Hypothesis”.12

Eighteenth-century medical practitioners frequently relied upon testimonial evidence to discern the efficacy of particular remedies. London physician James Jurin, for example, gathered testimonials in “good Baconian fashion”, tabulated the results, and based his conclusions upon “matters of fact” that could be demonstrated numerically.13 Through numerical representations, a patient’s anonymity would be maintained, a focus on success would sidestep religious and ethical debate, and charges of quackery would be squelched. In conclusion, basing medical practices upon evidence derived from this numerical method made them appear “more philosophical and hence, legitimate”.14

“Experience” and “experiment”, two expressions that were synonymous in Romance languages, were also used interchangeably in discussing Bacon’s vision of evidence-based health-care. For Bacon, only “ordered experience” that was founded upon methodological investigation, measurable criteria and objectivity counted as “evidence”, whereas “ordinary experience” based solely upon chance observation and subjectivity did not.15 His suggestions for revolutionising the experiential and experimental basis of science were more formally embodied in the formation of London’s Royal Society in 1660. This elite body, whose Fellows included the city’s leading physicians and many prominent promoters of chocolate for health, undertook the task of critically appraising the current state of knowledge. Their motto, nullius in verba – upon...