![]()

1

Introduction

Magazines are rich texts to study: of variable presentation and layered meaning, with multiple authorship and elusive target audience, they present endless challenges of interpretation and critique. However, their influence, authority, popularity and cultural competence make them significant objects of critical enquiry, be they print periodicals or broadcast programmes. A magazine can offer a whole ‘world’ to its readers in terms of outlook and instruction, apparently embracing every aspect of life, nurturing body and mind, teaching lifestyle, encouraging success at home, in the workplace and in all manner of relationships, and so seemingly leading the way to a more fulfilled existence. Magazines are perhaps the ultimate zeitgeist media form. It is precisely this expansive authority, dealing in the detail of lives that draws both readers and critics. Any media form that purports to guide its target audience to a better version of themselves, through direct and intimate communication styles, is a media form with a political agenda. The political intention may be overtly stated or latently enfolded between the lines of articles and advertisements. It may be the impetus of capitalism in the pursuit of profit and corporate competition or it may be gender politics or an anti-hegemonic stance that provides the imperative. The magazine form lends itself to opinionated expression.

Magazines are rich texts, but they are also hugely diverse and intricately complex. Their varied content opens up numerous avenues for critical investigation, and their real and imagined target audiences lead to a considerable range of cultural and social modes of understanding. Consequently meaning, reception and cultural competence can remain fascinating, but elusive. Further analysis, it seems, is always possible of magazines. Their depth in years, volumes, issues or programmes, their breadth across a vast array of subjects and their interconnectedness through publishing house and associated industries such as advertising, present rather daunting objects of study. Not only do some magazines last for decades, but studying their reach can be extensive work, encompassing changes in society, reflecting diverse engagements with issues of gender and class, exposing industrial processes and functions, showcasing the talents of writers and editors and demonstrating a remarkable cultural embeddedness. Meaning and communication, meanwhile, are conveyed variably and often unknowably between writer and reader, and there are endless permutations in the format, content, tone and appearance of magazines. Moreover, the very term ‘magazine’ has lent itself to multiple interpretations and uses and is used to indicate any media genre with mixed content: a television programme, radio broadcast, web page, newspaper supplement, even a home-made scrapbook might call itself a magazine. The term is a capacious one.

In order to investigate the flexibility of the format we refer to as a magazine, each of the following chapters looks at an example that highlights a different way of understanding the context and function of the magazine. However, this is also a study of the work that magazines might do for women. Much critical work has been produced on the commercial, consumer-oriented print magazine for women and such magazines have long been understood to be important to women readers. From the very first, women’s magazines have offered advice, information, companionship and inspiration and many have possibly concomitantly offered a persuasive image of a reactionary, conservative femininity into the bargain. Critical work in the field has discussed and revealed how such ideological constructions of women have potentially imposed or, at best, reflected, patriarchal restrictions on women’s lives, in terms of a pervasive domesticity, an adherence to ideals of beauty, a slavishness to fashion, the establishment of constraining and conflicted modes of female feminine behaviour and so on. Work by feminist scholars in this field has been invaluable in both recognising the lure and potential persuasiveness of magazine editorials and images, and understanding the compellingly intimate personal dimension of this form of media communication. Some of the major writings are briefly outlined later in this chapter.

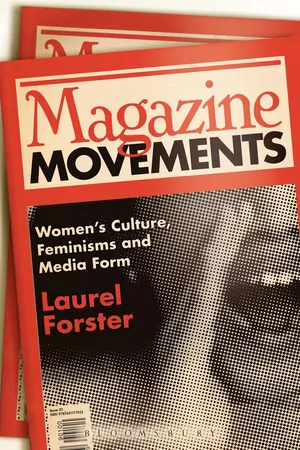

However there is a paradox here. Much of the existing body of work on women’s magazines, engaging with aspects of the ‘cult of femininity’ in its various insidious guises and pointing to the contradictions inherent in ideological constructs within magazines, concentrates on examples of commercial, capitalist production of the service magazine, or the glossy domestic or celebrity publication. This focus can lead to readings of women’s magazines as characteristically closed texts that urge a predominant meaning or mode of consumption.1 This study does not take issue with those readings. Such studies have paved the way to penetrating these complex texts we call magazines: they have drawn on different aspects of magazine content and political interpretation, reflected on reader interpretations and industry practices, and generally and convincingly demonstrated the significance and influence of the form. My argument is not with the conclusions of such studies, but with the exclusivity of their choice of magazines. Whilst there have been good reasons for studying mainstream commercial magazines with mass circulations and therefore mass influence, this study opens up for consideration a range of examples that moves away from the publications that have dominated critical commentary for so long. The aim of the following chapters, therefore, is to add breadth of media form, including radio and television broadcast and Internet formats to the usual print media genre. Further, Magazine Movements explores the homespun, the minority-specific, the little-remembered and the politically-oriented magazine for women. Many of the examples are out of the way, of limited circulation or of unusual presentation, stretching boundaries of form, suggesting new modes of presentation and meaning, and engaging in different ways with their audience.

Magazine Movements has two central modes of enquiry: firstly to investigate and consider the expansive form of magazines for women; and secondly to reflect upon how magazines simultaneously address, engage with and understand their female target audiences, that is, how magazine communication is staged. I investigate the structure and form of magazines across different media genres, and by extending my examples to include radio, television and the World Wide Web, as well as print, explore the pervasiveness and importance of this media form. My second aim is to employ a more varied set of critical frameworks to bear on these unusual magazines, frequently focusing on the initial stages of a magazine as the moment of start-up is crucial in establishing the manner of communication. Even commercial magazines, in the minority in this study, communicate variously. They are polysemic texts: on the one hand, they frequently represent the ideological strictures, gender norms and assumed subjectivity of the dominant classes, acting as a vehicle for the commercial requirements of producer and advertiser contributing to the capitalist system, yet on the other hand, this is a form which has been so enthusiastically embraced by women over a number of centuries, that the positive energies of aspects of the magazine format must be equally important. It is possible, perhaps, that women have been and continue to be duped into a blind observance of and adherence to the messages of the magazine, yet this seems unlikely for all of us who engage with and enjoy certain magazines at various times.2 Commercial magazines, in their multi-layered construction of meaning, offer oppositional kinds of interest and entertainment, simultaneously providing practical advice and a fantasy world, giving authoritative instruction as well as passing on gossip, engaging with uncomfortable social realities on one page and dispensing aspirational discourses on another. In this way, different component parts of magazines produce different potential meanings and interpretations.

In response to the obvious question of how magazines achieve this and yet still retain their popularity amongst readers, this volume argues that changing, disjointed, even conflicting and contradictory communication is the norm for commercial magazines, and for some small and non-commercial magazines too. Such ‘polyvocal’ texts are not purveyors of harmonised or consistent messages, rather they embody difference, and divergence.3 The very form of the magazine enables a breadth of views and participations.4 Its conventions of articles, snippets, features, letters and so on should be viewed as hospitable to diverse opinion, as storehouse forms rather than necessarily cohesive texts. In discussing the processes of signification of a range of texts, all called magazines, this present volume hopes to approach an understanding of the diverse communicative strategies possible through this important media form.

Women’s magazines have often reflected dominant, socially constructed images of womanhood, and yet have also engaged with issues of real concern to women; some, proving their diversity of address, seem to do both simultaneously. Furthermore, whilst some women’s magazines may have remained seemingly impervious to changing social circumstances for women, others have reflected those developments. The relationship of the magazine to the prevailing historical, social and cultural situation for women is an important aspect of the magazines selected for discussion here. It is the particular way that magazines have alighted upon, or responded to, an issue for women – and there have been many across the long twentieth century – that has drawn my attention to the particular magazine. Whilst not all the magazines in this study could be labelled as overtly and politically ‘feminist’ in a narrow sense, in another broader sense, they all enter into a female discourse, identifying and attending to the particular needs of women.

From as early as the 1960s, feminist writers have criticised and discussed women’s magazines. Yet it was to the magazine format, later in that same decade, that many women’s liberation groups turned when they wanted to express themselves and reach out to potential new members, and in so doing were following a pattern established by many suffrage groups of the first wave of British feminism. Of course, different types of magazine communication obtain here: critics were condemning prevailing ideologies prominent in commercial domestic ‘service’ magazines,5 whilst suffrage and liberation groups were producing official organs or newsletters to promote oppositional political ideas. Nonetheless, formats of the conventional magazines were copied by feminists, layouts were mimicked and contents reworked. Precisely because the magazine is a highly flexible form, it has been able to accommodate a varied representation of, and address to, a spectrum of women. Equally, if the magazine form has variously worked both for and against female politics, then the differences, dualities and similarities of magazines for women may be better understood by a close examination of their formal structure and approaches to readership communication.

Alongside a reflection upon the communication strategies adopted by magazines as they address and appeal to their target readerships, are observations concerning how those readers talk back. Studies in print media have demonstrated that magazines and periodicals express an exchange of ideas, not a static pronouncement. Ideas might be exchanged with society in general, with institutions, with other media forms, with particular groups of women (and men) and, not least, with individuals. The exchange and dialogism permitted by the magazine gives it its lifeblood: it refines its form and content; it keeps it current. The relevance of subject matter to the readership and the cultural moment, the adaptability to different modes, and the cultural competence of a magazine, offer up a complex set of discussions.

The social and political movement that lies at the heart of this study is feminism in its broadest sense, and the magazines I have chosen to discuss have an interest, at some level, in the social and individual progression of women. Feminism, with its history, diversities and contradictions, its promotion of gender equality and of female cultures, its variety, exclusivity and inclusiveness, has touched every magazine in this volume. All the magazines engage with aspects of female politics, and sometimes feminist politics, to some degree or other. That is, they take one or more aspects of women’s lives and seek to develop understanding, consciousness and engagement through identity formation, sharpening of subjective consciousness, education or collective action. In each chapter, my aim has been to reach an understanding of the significance of the magazine in its address to the individual female reader, or viewer, and the broader female audience.

The critical field of women’s magazines

A range of critical approaches have proved useful in this study in trying to understand the form and communication strategies of magazines that, in their different ways, address different arenas of female politics. To gain a sense of a magazine’s communicative abilities is to assess how well it understands its audience, how it manages the delivery of its messages and information and how it deals with the target audience’s responses. The chapters in this study draw on a full range of previous work in this field.

In the brief overview below, I have divided the major discussions of women’s magazines into two overlapping groups: general and specific discussions of women’s magazines. The general discussions have been useful in understanding the ideological imperative and potential reception of a range of mostly commercial magazines, for comprehending the historical sweep of the magazine and the influence of the magazine industry over the centuries. The specific discussions provide more focus on either historical period or particular audiences or particular magazines.

From at least as early as 1963, it has been clear just how important women’s magazines have been in shaping and reflecting women’s consciousness and identity. Betty Friedan’s seminal The Feminine Mystique describes the ‘happy housewife heroine’ as a creation of American women’s magazines of the post-war period:

In the second half of the twentieth century in America, woman’s world was confined to her own body and beauty, the charming of man, the bearing of babies, and the physical care and serving of husband, children, and home. And this was no anomaly of a single issue of a single women’s magazine.6

Broadly, Friedan charts a history of women’s magazines in which there is a withdrawal from female independence, ambition and engagement in the wider world in the 1930s to a female persona of child-like dependence, heroic only in childbirth, subsumed into a man’s life in an ideology of ‘togetherness’, finding true happiness in the materiality and domesticity of being a housewife. Friedan laments the diminishment of the life of the mind within women’s magazines and points to other concomitant factors such as the deterioration of the quality of fiction writing, and the commercial imperatives imposed on the editor. In particular, Friedan is critical of the way that women editors and fiction writers of the late 1940s and 1950s were replaced by male editors and ‘Housewife Writers’ writing formulaically to a male perception of the new housewife. As an ex-editor of women’s magazines herself, Friedan is in a position to point out that female writers and editors of the period were not themselves confined to a domesticated femininity. Writers may have been enjoying their domestic lives, but this was alongside their careers, and editors did ‘not bow to the feminine mystique in their own lives’. The paradox of seeming equality in the workplace and yet the intense portrayal of the housewife-mother figure in women’s magazines is not lost on Friedan, as she goes on to discuss the need for a new female identity other than femininity.7 Although criticised for her dual position, Friedan’s observations struck a chord and have remained important. In Chapter 2, I suggest that wartime circumstances pulled away from the purely feminine and women’s identity was viewed changeably by one such domestic women’s magazine.

The ideological power and prominence of the ‘cult of femininity’ and its magazine construction has been critically analysed and discussed in foundational texts such as Forever Feminine by Marjorie Fergusson (1983).8 Some studies point to the contradictions and tensions in women’s magazines, and Women’s Worlds, for example, by Ros Ballaster, Margaret Beetham, Elizabeth Frazer and Sandra Hebron, argues that women’s magazines present women’s subjectivity as the problem and the various elements of the magazine as the solution. This winning formula, despite production changes and diversification, has been a fundamental means of survival of the genre across the...