![]()

PART I

Settings and Eras

![]()

1

The Slave Trade and Slavery in the Americas

Transcontinental Trends

Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Christian Western Hemisphere relied on the enslavement of Africans and their descendants to varying degrees. To this end, thousands, and later tens of thousands, of men, women, and children were deported from Africa to the Caribbean and the American continent every year for nearly four centuries. In total, according to estimates by Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, approximately 12,332,000 Africans were loaded onto slave ships bound for the Americas.1 In all likelihood, an additional 8 to 10 million died during capture, marches to African ports, or the long wait in coastal depots. The slave trade initially recruited its victims in Senegambia, via Gorée Island, before gradually spreading across the entire coast of Guinea and its inland regions. During the eighteenth century, it extended into Angola and the Kingdom of Kongo, reaching as far as their vast interiors, exporting captives primarily from Elmina, Ouidah, Calabar, Cabinda, and Luanda. That region continued to supply the majority of slaves in the nineteenth century, when Mozambique, until then mainly a tributary of the Arabian Peninsula and the western coast of India, was also impacted by the transatlantic slave trade. Deported Africans therefore came from vastly different cultures, the most heavily represented being, north of the equator, the Wolof, Mandinga (including the Bambaras), Ashanti (including the Akans, called the Coromantee by the British), Gbe (Ewe, Fon), Yorubas (called the Lucumí by the Spanish), and Igbos (or Ibos), and, in the south, the Kongo and Bantus (including Landas and Mbundu), and, in Mozambique, the Makua.2

The forced departures of so many Africans to the Americas, which joined existing Saharan and Arab slave trades that began in the second half of the seventh century,3 had significant demographic, economic, and political consequences on all of sub-Saharan Western Africa and Mozambique.4 Of the 12,332,000 Africans ripped from their homeland, nearly 2 million (or 16 percent total) perished during the transatlantic voyage. Still, 10,538,000 survived the crossing to be sold as slaves in American ports.5 Death remained a constant threat for the survivors, a large number of whom died in the year following their arrival, in ports, during travel to the mines, plantations, or households to which they were destined, and at their new places of work. During this interminable journey, millions of men, women, and children also died prematurely from maltreatment, exhaustion, hunger and thirst, disease (particularly smallpox), and despair. Some committed suicide or were killed as they attempted to rebel.6 According to several estimates, those still alive one year after arriving in the Americas represented less than half of those who were originally captured in Africa.7

African survivors would nonetheless rapidly transform the demography and sociology of the Western Hemisphere. Though decimated by the slave trade, Africans far outnumbered other groups that reached the “new” continent until the 1820s: they were at least four times more numerous than European immigrants.8 These involuntary migrants, young men for the most part,9 adopted a variety of strategies to survive and in some instances escape enslavement. Some had sexual relations, willingly or otherwise, with persons of European and Amerindian descent, thereby accelerating miscegenation. Some within that group obtained their freedom, creating a socioracial category of “free people of color,” meaning free blacks and Afro-descendants who, though subjected to considerable legal discrimination, challenged by their very existence a system of slavery based on the “race” of Africans and their American-born descendants.

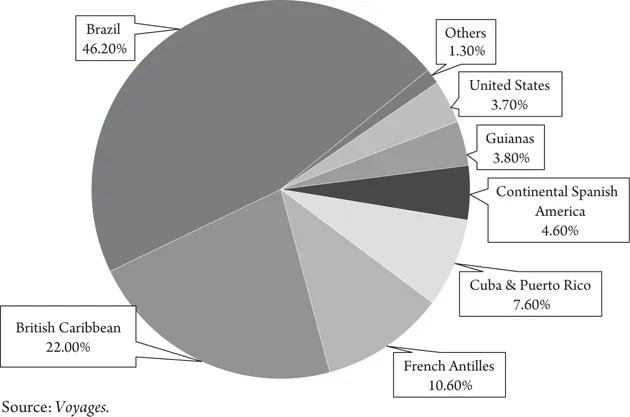

Slavery affected every region in the Western Hemisphere, from North to South, Atlantic coast to the Pacific via the Caribbean. As graph 1 demonstrates, no country relied on slavery more continuously and on a more massive scale than Brazil, which imported African slaves uninterruptedly from 1561 to 1856. According to estimates by The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, 46.2 percent of the 10,538,000 African men, women, and children brought to the Americas went to Brazil. The British West Indies followed, with 22 percent of that total, half of which was represented by Jamaica alone. Next came the French Antilles, with 10.6 percent (70 percent represented by Saint Domingue), and the Spanish Caribbean, with 7.6 percent (notably Cuba, with Puerto Rico far behind). But if we add the Dutch and Danish West Indies,10 the Caribbean islands as a whole received 41.7 percent of African slaves. The remaining 12.1 percent was brought to the non-Brazilian continental Americas: 4.6 percent to Spanish colonies, 3.8 percent to the Guianas (notably Dutch Guiana and, to a lesser degree, the British and French Guianas),11 and only 3.7 percent to the continental colonies of Great Britain and the future United States.12 However, that geographic distribution only accounts for slaves arriving directly from Africa, whereas some, particularly those sent to Jamaica, had been immediately reexported to Spanish and British colonies in the Americas.13

The slave trade was far from uniform or constant. Between 1501 and 1650, a period during which the Portuguese, until the 1620s, and then the Dutch had a monopoly on transatlantic slave imports, 726,000 African captives in total were brought alive to the Americas, primarily to continental Spanish colonies and Portuguese Brazil. From 1650 to 1775, during Great Britain and France’s concurrent participation in the slave trade and the development of sugar plantations in the Caribbean and Brazil, 4,796,000 Africans were brought to the Americas. Cargos during the final 111 years of the slave trade, from 1775 to 1866, surpassed that number, delivering 5,016,000 new captives to the region.14 What’s more, that massive amount, which corresponds to half of the 10.5 million Africans transported across the Atlantic, was reached despite the influence of Enlightenment philosophy, growing recognition of freedom as a fundamental right, the transition to independence in the continental Americas, and the gradual legal abolition of the slave trade.

Graph 1. Destinations of Enslaved Africans Disembarked in the Americas, 1501–1866

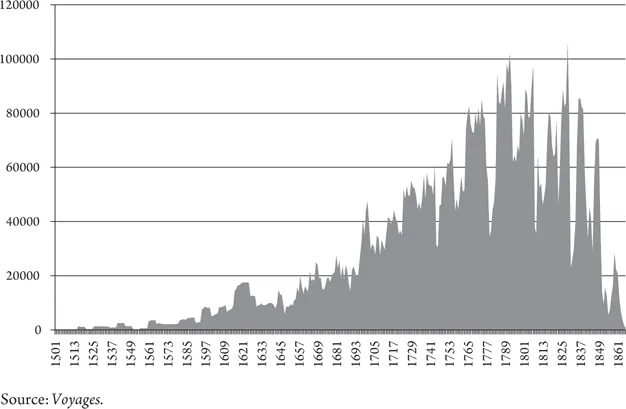

Graph 2 demonstrates the evolution of annual imports of enslaved Africans from 1501 to 1866. It shows that the slave trade grew continuously from 1500 to the early 1620s, a decade during which more than 17,000 Africans were imported to the Americas each year. The slave trade then slowed, with approximately 10,000 slaves arriving each year for a quarter of a century; after 1655, it increased almost continuously, reaching more than 70,000 Africans in 1755 on the eve of the Seven Years’ War. Since 1766, following a drop during the war, the slave trade imported on average 78,000 captives each year until a new decline during the U.S. War of Independence (1776–81). But the decade of 1784–93 marked a climax with imports reaching nearly 91,000 Africans on average per year. From 1794 to 1824, the Haitian Revolution, the Napoleonic Wars, the abolition of the Danish, British, and U.S. slave trades in 1807–8 and the Dutch trade in 1814, and finally the Spanish American wars of independence caused major disruptions to the slave trade, which nonetheless maintained on average more than 64,000 Africans imported annually for three decades. In 1825, and despite Spain’s, France’s, and Portugal’s acceptance of a declaration relative to the universal abolition of the slave trade in Vienna ten years earlier, the importation of slaves saw a meteoric rise, once again reaching nearly 88,000 Africans per year between 1826 and 1831. In fact, the historical record was reached in 1829, when as many as 106,000 captives were disembarked, nearly all in Brazil, Cuba, and the French Antilles. From 1831 to 1859, despite the signing of new treaties banning the slave trade, nearly 54,000 Africans on average were illegally imported each year, notably by Brazil and Cuba. After 1856, when Brazil ended its contraband trade, Cuba, the last colony to continue violating treaties, imported another 148,000 captives by 1866, when the last 722 African slaves arrived on the island, marking an end to over three and a half centuries of human trafficking.15

Graph 2. Numbers of Enslaved Africans Disembarked Each Year in the Americas, 1501–1864

Africans and their enslaved descendants contributed enormously to the development of every economic activity in American societies, from domestic service to transportation, mines to plantations, and brute manual labor to highly skilled craftsmanship, writing, and artistic creation. Slaves further represented considerable capital whose value was often superior to that of the land or buildings on an estate, and which the owner could sell, rent, pawn, use to reimburse debts, and bequeath. Slavery was a primarily rural phenomenon: in places where indigenous populations had been wiped out or were dispersed, producers of gold, indigo, tobacco, sugar, coffee, cocoa, rice, and cotton, the exportation of which made European nations and colonial and American elites rich, were most often slaves of both sexes. Many cattle breeders, muleteers, porters, rowers, and peddlers were slaves as well. Cities and small towns also had sizable enslaved populations, composed notably of women and girls performing varied domestic tasks, or working as cooks, washerwomen, ironers, peddlers, prostitutes, wet nurses, maids, waitresses, midwives, or healers. Urban male slaves served as, among others, stewards, valets, cooks, bakers, coach drivers, day laborers, construction workers, dressmakers, shoemakers, metalworkers, street vendors, horse grooms, musicians, or were assigned to military forces. Many lived with their masters, but some resided and worked independently, paying a fixed daily or weekly sum to their owners.16 As underlined by historian Herman Bennett, not only did urban slaves play a major role in city economies, they also conferred “cultural capital” on their masters and mistresses by boosting their social rank. The more slaves, often clad in livery, were owned by an aristocratic estate, the more its owners were held in high standing by society. For large landowners living in town, slaves were simultaneously the source (via the product of their nonremunerated work) and demonstration of wealth and social status.17

Peru and Brazil:

After the Amerindians, the Africans (1501–1650)

The first slaves reached the Americas shortly after Christopher Columbus in 1492. They were also present, alongside with free blacks and mulattos, among the conquistador armies that overthrew the Aztec and Inca Empires. From the earliest days of colonization, those slaves included ladinos (Europeanized slaves of African ancestry who came from the Iberian Peninsula) and bossales (non-Europeanized slaves who came directly from Africa, referred to as bozales in Spanish and boçais in Portuguese). At that time, slavery was well established on the Iberian Peninsula, particularly in the domains of domestic labor and urban craftsmanship. African slaves had supplanted their Moorish predecessors, and represented up to 10 percent of the populations of Portugal and Spain’s coastal towns. But it was on the islands off the Atlantic coast of northern Africa—São Tomé, the Canary Islands, and Madeira—that, beginning in 1450, the Portuguese and the Spanish developed a sugar plantation system based on the enslavement of countless Africans that would come to characterize the Americas.18

Yet nothing predestined African slavery to become as important as it did in the American colonies. In fact, when the Europeans arrived, there were likely some 57 million inhabitants in the Americas as a whole. That indigenous population represented a labor force from which the colonists could have drawn at length. Incidentally, the Spanish were initially eager to enslave natives in the Caribbean, as the Portuguese did to the Tupi-Guarani on the Brazilian coast. But those populations were quickly decimated due to their conquerors’ cruelty, diseases to which they lacked immunity, forced labor, and culture shock. Indigenous societies in the Caribbean and on the coast of Brazil were semisedentary and fragile, and nearly disappeared completely in the span of one century. Though the densely populated territories of the Aztec and Inca Empires were not completely depopulated, they nevertheless lost approximately 90 percent of their original populations between 1520 and 1620.19

The rapid and violent depopulation caused by colonization was denounced at the time by men such as the Dominican priest Bartolomé de Las Casas (1474–1566) who, after 1530, gradually persuaded the Spanish monarch to ban the enslavement of Indians. Nonetheless, the encomienda system, in which the king granted conquistadors indigenous communities from which they could extract labor and tribute, endured far beyond his royal ban of 1542. Since the second half of the sixteenth century, Spain also transformed the Inca system of tributary labor, mita (called repartimiento in Mexico), by forcing every village community to supply a quota of temporary workers to mines, plantations, and weaving mills three times a year. In parallel, authorities forcibly resettled segments of the surviving Amerindian population to pueblos de indios near colonial labor centers, all while forbidding them from settling in cities.20

By 1550, nearly every Amerindian population had become too small to form a durable labor force. At the same time, neither Spain, already strained from its vast European empire’s demands for men, nor underpopulated Portugal were in a position to compensate for Amerindian demographic losses by sending colonists or indentured servants to the Americas. So the two monarchies turned to African slavery in the form in which it existed in their African island colonies and the slave trade took hold, monopolized by the Portuguese. Between 1500 and 1650, continental Spanish America and Brazil each imported a total of nearly 350,000 slaves.21

The main Spanish destinations were the colonies of Peru and Mexico, followed by Colombia and Venezuela, and to a lesser degree Central America and Ecuador. After a stop in Havana, Africans were sent to the ports of Veracruz in Mexico, Cartagena de Indias in Colombia, and Portobelo in Panama. Most were then taken, chained or bound, by foot and by boat, to plantation or mining regions. Those destined for Peru traveled either from Panama via the Pacific Ocean or from Cartagena via dangerous routes through Colombia’s sweltering plains and the glacial summits of the Andes. The high demand for slaves in Peru was due to colonists’ preference for the sparsely populated Pacific coast over the Inca center in the Andes, home to the majority of the colony’s indigenous people (by then regrouped in pueblos de indios), and to their reticence to undertake a mass displacement of that already weakened population toward the coast. By 1555, there were 3,000 bozales in Peru, half in Lima. One century later, Peru had a total of 100,000 slaves, representing between 10 and 15 percent of the population, and most of them were concentrated along the coast. Lima counted 20,000 slaves; along with free people of color, they represented half of its inhabitants. They worked as domestic servants, porters, sellers, washerwomen, unskilled workers, artisans, seamen, and soldiers, among other occupations. Some were assigned to forced labor in bakeries and weaving mills on the outskirts of Lima, at times chained alongside convicted criminals. South of Lima, approximately 20,000 slaves labored on sugar plantations in the Pisco and Ica regions. Many were assigned to the royal navy and to gold and silver mines in the South. Slaves were also charged with raising cattle and horses, while others worked as muleteers farther inland.22

During the same period, Mexico (or New Spain, which stretched from present-day Florida and New Mexico to Costa Rica) had some thirty-five thousand slaves, who represented less than 2 percent of its population. As in Peru, they were employed in a large variety of sectors including domestic work, crafts, and cloth weaving, as well as gold and silver mining, but they played a less important economic role due to a slight uptick in indigenous demographics after 1600. They were, however, essential in certain regions, notably Veracruz, where they cultivated sugarcane crops.23 Although Colombia, Venezuela, and Ecuador occupied a secondary position in Spain’s American empire at the time, slaves in those regions performed production-related and domestic tasks similar to those of their counterparts in Peru and Mexico. In the Popayán region, south of Colombia, growing numbers of slaves were assigned to farms and gold mines: slavery supplemented the encomienda system (though it was illegal) until it end...