![]()

CHAPTER 1

* * *

The Emergence of Bifactional Politics

I’ve got a Eugene dog, I got a Eugene cat,

I’m a Talmadge man from ma shoes to ma hat.

Farmer in the cawn field hollerin w’hoa gee haw,

Kain’t put no thirty dollar tag on a three dollar car.

—Fiddlin’ Joe Carson and Moonshine Kate

From the early twentieth century until the 1960s, Georgia and the rest of the South were one-party states, loyal to the party of Jefferson and Jackson.1 After the Democrats quashed the Populist revolt of the 1890s, Georgia, like the other southern states, moved to disfranchise both black and poor white voters. This one-party environment in the first half of the twentieth century did not mean there was a lack of political competition.

Throughout most of the South, intense, dynamic competition, often fought out through informal or personal organizations within party primaries, characterized the Democrats. Southern state parties managed an uneasy balance between these factions, which had myriad bases of support for their creation and sustenance. In many southern states, factional divisions involved cultural and economic gaps between the patrician, Bourbon white planters and elites of the Black Belt (the descendants of Jefferson’s noblesse oblige planter class) and the yeoman farmers from the predominantly white hill country (descendants of Jackson’s Scots-Irish freeholders). Sometimes politics centered on friends and neighbors, relations that V. O. Key Jr. describes in Southern Politics in State and Nation; city versus country; or regional rivalries. Whatever the source of division, there was usually competition for control of party nominations. Alabama, Florida, and Mississippi hosted multifactional politics, with different transient factions emerging to compete for brief periods of time. At the other end of the organizational spectrum, in Virginia, the Flood-Byrd machine dominated the commonwealth and quashed political competition for most of the twentieth century. In Georgia, Louisiana, and Tennessee, stable political organizations emerged to lend shape to state politics. These durable factions caused the opposition to coalesce as a single organization, producing bifactional politics.2

A bifactional political system developed in Georgia as a result of the convergence of the personality and campaign style of Eugene Talmadge and a set of political institutions—specifically, the county unit system, the white primary, two-year terms, and a malapportioned legislature that placed political power in the control of rural counties. This political system favored a rustic segregationist culture amenable to Talmadge’s brand of politics, which fused distrust of government and other large elite institutions with a set of policies designed to advantage the “poor dirt farmer.”3

COUNTY UNIT SYSTEM

To understand the electoral politics of the state is to recognize that Georgia never had one statewide election for governor but instead had 159 such elections, one for each county in the state, where local politicians were often anxious for political payoffs. The need to conduct 159 separate campaigns made the county more integral to the historic politics of Georgia than to those of any other state. In the Democratic Party primary, nominations were determined not by the votes of the people but by the votes of counties, which under Georgia election law were created more equal than the men and women who voted. The apportionment of political power in the legislature and in statewide elections was based on counties. As a result, political control of the county courthouse and its set of elected offices—sheriff, road commissioner, assessor, probate judge, clerk, coroner—offered the opportunity to wield political power as well as to command economic resources.

Georgia had used some form of county-based apportionment to elect statewide officials as early as 1777, when the original state constitution apportioned lawmakers to counties and towns and then used the counties to pick electors to choose an executive council. The modern system, institutionalized in the Neill Primary Act of 1917, had started in 1874 with Fulton County’s practice of using primaries to choose Democratic convention delegates. A majority of counties had adopted that approach by 1886, and it was later extended to all counties as a Democratic state party rule in 1892. The Atlanta Journal greeted passage of the Neill Primary Act by describing it as “contrary to the basic principles of popular government . . . political jugglery in which the will of the people can be thwarted.” Other papers saw in the act a mechanism to control the black bloc vote.4

Winning nomination in the decisive Democratic primary for statewide offices and in some congressional districts required accumulating county unit votes. The nomination for governor required a majority of the county unit votes, while a plurality sufficed for other statewide offices. With 159 counties, Georgia has more than any state other than Texas. Like the Electoral College, which allocates all of a state’s electoral votes to the plurality winner in the state, the county unit system allotted a county’s unit votes to the recipient of a plurality.5 The winner of a plurality in a county received its unit votes. Beginning in 1932, there were a total of 410 unit votes, meaning that a gubernatorial candidate needed 206 to win the nomination (and by default the election). If no candidate reached 206 unit votes, a runoff would be held.

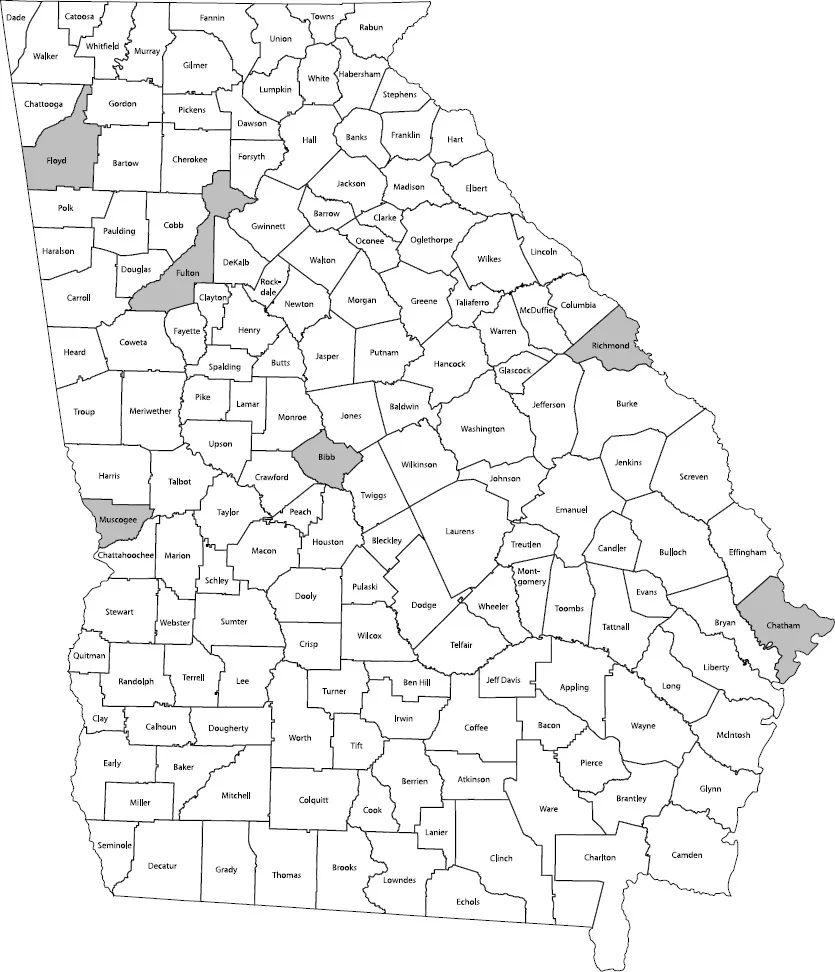

The county unit system was less sensitive to population differences than the Electoral College. The eight most populous counties shown in map 1 had six votes each. While the eighth-most-populous county might vary depending on the most recent census, the counties consistently in this group were Bibb (Macon), Chatham (Savannah), DeKalb (part of Atlanta), Floyd (Rome), Fulton (Atlanta), Muscogee (Columbus), and Richmond (Augusta). Town counties (the next thirty largest in population) each had four unit votes. The town counties included Baldwin (Milledgeville), Clarke (Athens), Decatur (Bainbridge), Gwinnett (Lawrenceville), Hall (Gainesville), Troup (LaGrange), Upson (Thomaston), and Ware (Waycross).

The 121 rural counties had a total of 242 unit votes and, if united, could easily outvote the urbanized counties. Statewide candidates could win with exclusively rural support. Any three rural counties could negate Fulton County’s six unit votes despite having only a fraction of the larger county’s population and voters. The inequity of the system became more exaggerated after World War II. Rural counties accounted for half the state’s 1920 population; by 1960, they had only 32 percent of the population yet still controlled 59 percent of the unit vote.6 After several unsuccessful court challenges, the Supreme Court in 1962 struck down the county unit system as violating the Equal Protection Clause.7

Rural influence in the Democratic primary, coupled with jealousy and distrust, made it impossible for candidates from Atlanta to win the state’s highest offices. During the forty-five years that the county unit system under the Neill Primary Act determined nominees for governor, one nominee came from a six-vote county, six came from four-vote counties, and ten came from two-vote counties, including four-time winner Gene Talmadge and two-time winners E. D. Rivers and Herman Talmadge.

MAP 1. Urban counties under the county unit system.

Candidates had an additional incentive to concentrate their efforts on rural counties. Joseph L. Bernd estimates that at least twenty-one counties were boss-controlled, while an Atlanta Constitution editor estimated that as many as sixty could be bought.8 Some counties consistently supported Talmadge, while others were anti-Talmadge. The members of yet a third group sought to ensure that they were on the winning side. Backing the winner in a gubernatorial election positioned a county to receive funding for highway projects and other programs and might attract state funds to local banks. The presence of a set of counties that could be bought made the task of campaigning even easier. Successfully courting the sheriff or whoever wielded power in three rural counties could take the place of the expensive and time-consuming investment needed to win a six-vote county. Similar negotiations and machining of the vote occurred in other southern states, most notably Tennessee.9

Herman Talmadge said of Georgia politics in the 1930s, “Those were the days of the courthouse rings and the county unit systems and the politicians wanted governors, when they had to do something in their county, they could be a deputy governor of their particular county.”10 Local bosses or courthouse gangs eagerly exchanged their counties’ votes for a piece of state government power or patronage. A courthouse ring or gang usually consisted of elected county officials, including the sheriff, county ordinary (today called the probate judge), county commissioners, and the tax commissioner, who together controlled local politics. One former legislator commented that the way to know how a county would vote in an upcoming election was to see who supported the sheriff and county ordinary.11 Sheriffs and ordinaries often held broad sway over tax collection, voter registration, and other functions of county government. Georgia’s unique governing arrangement of having a sole commissioner was much more widely used into the 1950s, and when a county had a single commissioner, that individual was usually a key player.

Not all rural counties, however, were bossed. For those that were not, Roy Harris, onetime Speaker of the Georgia House of Representatives and political kingmaker, explained, “If you’re going to win in Georgia, you’ve got to know the counties. . . . You got to know how the people think, and what they want.”12 For some counties, this meant understanding what local legislative priority needed to be dealt with in the next legislative session. For others, it meant understanding the sort of political appeal that would resonate with voters and local leaders. In southwestern Georgia, where the counties had large black populations, white voters were most open to racial appeals by candidates; predominantly white North Georgia counties were relatively immune to such appeals.13

SETTING THE SCENE: GEORGIA IN DEPRESSION

Georgia in the years before World War II was more like 1890 than 1960. Prewar Georgia depended heavily on agriculture and experienced slow population growth. During the roaring 1920s, the U.S. population grew by seventeen million, but virtually none of that growth took place in Georgia, which stagnated, adding only thirteen thousand persons. Georgia’s population grew by less than 8 percent from 1920 to 1940 even as the nation expanded at three times that rate. Atlanta grew, but the rest of Georgia actually lost population through 1930 before topping the three million mark in 1940.

Growth did not mean modernization. Many Georgians lived isolated lives on dirt roads rendered impassable by winter rains. In ninety-three counties, more than two-thirds of residents lived in rural areas, usually with most of them dwelling on plots of less than twenty acres. On Saturdays, the more successful would trek to the county seat to shop and gossip. Poorer hired hands might make it no further than the commissary operated by the landowner who hired them, where they would put some fatback, molasses, and cornmeal on the tab to be settled once the cotton crop came in later that fall. In the textile mill villages of North Georgia, the living was a little better. Mill-owned housing for workers had electricity and sometimes indoor plumbing. However, the wages paid—usually not much more than a dollar a day in 1930—were consumed by rent or credit at the company store.

Children walked to school. City youngsters might have a full academic year, but farm kids often had school for only a few months. Classes might be interrupted for a couple of weeks in September, when all hands were needed to bring in the cotton crop, which accounted for two-thirds of Georgia’s agricultural economy. The white schools in Georgia’s segregated school system (operated under the Supreme Court’s separate but equal ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson) were often poorly funded but nonetheless might have as much as sixty times the support meted out to the black schools, many of which were one-room affairs or located in churches.14 Parents of the poorest children kept them at home since they could not afford to purchase the textbooks or decent clothing. Even youngsters who made it to school went barefooted deep into the fall and then shed shoes and socks with the first warm breaths of spring. Outside the urban centers, literacy and education rates remained low, especially among men. Black education was not a priority anywhere in rural Georgia. During the days of slavery, teaching a black person to read or write violated state law. An illiterate labor force is easier to manage, and the stagnant economy of Georgia below the fall line did not require literate labor. It required cheap labor.

Georgia outside of Atlanta had never recovered economically from the Civil War. A collapse in cotton prices after World War I coupled with the advance of the boll weevil across the South triggered an agricultural depression that placed Georgia cotton farmers in a precarious position. When the Great Depression hit Wall Street in 1929, rural poverty became even grimmer, with many marginal landowners seeing their few acres foreclosed; even some of the larger farming operations fell into receivership. For example, by the mid-1930s, John Hancock Life owned about three-quarters of the prime farmland in Greene County as a result of mortgage defaults and foreclosures.15 During hard times, the large landowner might become a smaller landowner; the small landowner and the sharecropper, facing destitution, might be unable to replace the milk cow or mule should it die. As the depression worsened, already rare “luxuries” such as a gingham dress for the wife, coffee, a stick of candy for each child, or tobacco for the father became even scarcer. Indeed, in the late 1920s, as the agricultural depression settled across the Cotton Belt, many planters abandoned wages and returned to a barter labor arrangement, offering credit at the “owner store” against the sale of the future crop.

Sociologist Arthur Raper’s intensive study of Greene and Macon Counties provides income figures just before the onset of the depression and seven years later for African Americans clinging to the bottom rungs of the economic ladder. From 1927 to 1934, average annual incomes for blacks in Greene County declined by half, to $150, while in wealthier Mac...