![]()

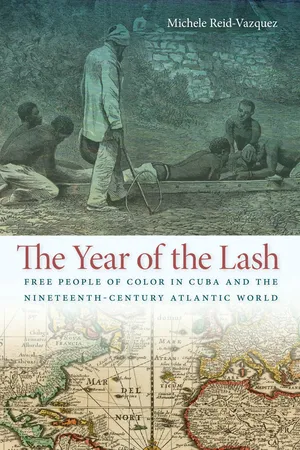

THE YEAR OF THE LASH

Free People of Color in Cuba and the Nineteenth-Century Atlantic World

MICHELE REID-VAZQUEZ

![]()

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1 “Very Prejudicial”: Free People of Color in a Slave Society

2 Spectacles of Power: Repressing the Conspiracy of La Escalera

3 Calculated Expulsions: Free People of Color in Mexico, the United States, Spain, and North Africa

4 Acts of Excess and Insubordination: Resisting the Tranquillity of Terror

5 The Rise and Fall of the Militia of Color: From the Constitution of 1812 to the Escalera Era

6 Balancing Acts: The Shifting Dynamics of Race and Immigration

Conclusion

Notes

Bibliography

Index

![]()

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The development and completion of The Year of the Lash has been a shared journey. This project would not have come to fruition without the initial support of several faculty at the University of Texas at Austin. I owe a special thanks to Aline Helg and Toyin Falola, who shepherded the dissertation phase of this study and continued to make suggestions as I converted the work into a book manuscript. I would also like to thank Jonathan Brown, Ginny Burnett, Susan Deans-Smith, Myron Gutmann, James Sidbury, and Pauline Strong for their guidance and support.

Critical financial assistance from the following institutions and organizations facilitated research in Cuba and Spain: the University of Texas at Austin’s Department of History, Institute of Latin American Studies, College of Liberal Arts, and Study Abroad Office; the Fulbright Commission, the Conference on Latin American History, and the Program for Cultural Cooperation at the Spanish Ministry of Education, Culture, and Sports in United States Universities. The knowledgeable staff at the Archivo General de Indias in Seville, the Archivo Histórico Nacional in Madrid, and the Archivo Nacional de Cuba, the Biblioteca Nacional José Martí, and the Instituto de Literatura y Lingüística in Havana, as well as the insights of Asmaa Bourhass, Tomás Fernández Robaina, Fé Iglesias García, and Pedro Pablo Rodríguez enriched this study.

Numerous institutions provided financial support for revising the manuscript. A postdoctoral fellowship from the Center for the Americas at Wesleyan University enabled me to initiate changes and conduct additional research. I especially thank Ann Wightman, who provided early comments on converting the dissertation to book form, as well as Demetrius Eudell, Patricia Hill, Kēhaulani Kauanui, Claire Potter, Lorelle Semley, Anthony Webster, and Carol Wright for creating a collegial atmosphere in which to nurture this project. I also thank Adriana Naveda Chavez-Hita for her guidance and Irina Córdoba for her research assistance in Mexico. Scholarships from the Newberry Library and the University of Florida allowed me to explore their rich collections, and funding from my home institution, Georgia State University, facilitated indexing and the presentation of chapters-in-progress at conferences. I would also like to thank Jeff Needell and Richard Phillips for their assistance and hospitality in Gainesville.

A postdoctoral fellowship at Emory University’s Fox Center for Humanistic Inquiry and a summer scholarship from the John Carter Brown Library enabled me to complete manuscript revisions. My interdisciplinary reading group with Regine Jackson, Esther Jones, and Yael Simpson Fletcher was phenomenal, and Yael’s editorial and indexing skills have been invaluable. Lively discussions with staff and scholars in both settings, particularly Keith Anthony, Colette Barlow, Martine Brownley, Amy Erbil, Hazel Gold, Philip Misevich, Mark Sanders, and Rivka Swenson in Atlanta, and Nicholas Dew, Elizabeth Maddock Dillon, Evelina Guzauskye, Javier Villa-Flores, Ted Widmer, and Ken Ward in Providence, helped enhance this work, as well as my developing project on race, freedom, and migration in the age of revolution.

Several scholars took time from their busy schedules to review individual chapters and offer insightful suggestions. Toyin Falola, Aline Helg, and Jane Landers provided important commentary on the opening sections. Caroline Cook, Mark Fleszar, Frank Guridy, and Jeffrey Lesser shared unique perspectives on analyzing black mobility and Rachel O’Toole offered thoughtful questions regarding urban labor and black resistance. Amanda Lewis, Ben Narvaez, and Christine Skwiot’s expertise on the Chinese in the Caribbean and Spanish America and labor migration, respectively, aided the formulation of the final chapter. Sandra Frink read multiple versions of the conclusion with patience and a critical eye toward illuminating the humanity of free people of color until the last word.

I received additional intellectual support from scholars and friends at Georgia State University (GSU) and across the country. At GSU, my thanks go out to Mohammed Hassen Ali, Robert Baker, Carolyn Biltoft, Kimberly Cleveland, Ian Fletcher, Jonathan Gayles, Amira Jamarkani, Kelly Lewis, Jared Poley, Jake Selwood, Shelley Stevens, Cassandra White, and Kate Wilson for their intellectual exchange and friendship. I bounced professional and personal issues off of mi hermano, Charles Beaty-Medina, and mis hermanas Beauty Bragg, Jenifer Bratter, Margo Kelly, and Anju Reejhsinghani. Adventures and conversations with Abou Bamba, Denise Blum, Sherwin Bryant, David and Sasha Cook, Duane Corpis, Michal Friedman, Kristin Huffine, Russ Lohse, Gillian McGillivray, Marc McLeod, Kym Morrison, Melina Pappademos, Lauren Ristvet, and David Sartorius also informed this project.

I am indebted to the editorial staff at the University of Georgia Press and the Early American Places series. My heartfelt thanks to Derek Krissoff, John McLeod, Beth Snead, and Tim Roberts for overseeing this project’s publication. The detailed commentaries by Peter Blanchard, Matt Childs, Ben Vinson, III, and anonymous reviewers enabled me to refine the final manuscript.

My family has steadfastly encouraged my goals, even when they wondered what I was up to when research carried me far from home. I thank my parents, Rebecca Farris Reid and Herman E. Reid, Jr., my siblings, Michael, Maurice, and Mabel, and sister-in-law, Sherri, for fostering my personal and professional creativity. I am especially grateful for my grandparents, Mabel Peasant Farris, Bernard Young Farris, Beatrice New, Herman E. Reid, Sr., and Emma Dean Reid; although you did not witness the completion of this book, your lifetime of nurturing flows through every page.

Jose Vazquez, mi amor, swept into my life during my travels and transformed it. The thousands of miles we have logged together since then—by car, plane, and train—reveal his enduring encouragement of my professional and personal development. The curiosity and energy of my stepson, Evan, and my niece and nephews, Simone, Desmond, and Maliq, continue to inspire me. Finally, the newest edition to our family, Reid Alejandro, arrived a few hours after I submitted the final manuscript for The Year of the Lash from my hospital bed. He has set the stage for new adventures to come. Muchísimas gracias a todos!

![]() THE YEAR OF THE LASH

THE YEAR OF THE LASH![]()

Introduction

At dawn on June 29, 1844, a firing squad in Havana executed ten accused ringleaders of the Conspiracy of La Escalera, an alleged plot among free people of African descent (libres de color), slaves, creoles, and British abolitionists to end slavery and colonial rule in Cuba. The group of condemned men represented some of the most prominent artisans, property owners, and militia officers within the colony’s free community of color, including the acclaimed poet “Plácido” (Gabriel de la Concepción Valdés).1 Convinced that recent rebellions involving slaves and free blacks formed part of a larger conspiracy, officials sought out its leaders and collaborators through a spectacle of arrests, tortured confessions, and public executions. In addition, Spanish colonial authorities in Cuba coerced hundreds of libres de color into exile, prohibited all free blacks from disembarking in local ports, banned native-born men and women of color from select areas of employment, and dismantled the pardo and moreno militia units.2 In the process, local officials redrew social and economic lines by extending race-based occupational restrictions and promoting immigration from Spain, the Canary Islands, and China to supplement or replace black laborers and reverse the “Africanization” of Cuba. The unprecedented wave of violence that engulfed Cuba in 1844 became known as the “Year of the Lash.” The violence and restrictive polices that accompanied it, however, persisted into the 1860s, in an attempt to silence and resubordinate the free population of African descent by stripping away decades of moderate political, economic, and social gains.

This book explores the lives of free blacks and their strategies of negotiating nineteenth-century Cuban society in the aftermath of the Conspiracy of La Escalera. It examines the impact of the Escalera era (1844–1868) on libres de color, their resistance to colonial policies of terror, and their pursuit of justice. As both a circum-and cis-Atlantic study, this work situates Cuba within its political, social, and economic relationship with Spain and within the late Spanish empire. It also features the transnational linkages sparked by migrations to and from Cuba involving free blacks, Spanish colonists, and Asian indentured workers. Petitions from exiles on the Gulf coast of Mexico and prisoners in Ceuta, Spanish Morocco, and Seville and Valladolid, Spain; exemption requests from conscripted militiamen in Havana; and clandestine networks forged by compatriots and African Americans in New York City demonstrate both formal and extralegal methods of adaptation and resilience. These ...