![]()

1

War on the Air

Europe has reached the point where all the highly developed means of communication serve constantly to strengthen the barriers “that divide human beings”; in this, radio and cinema in no way yield the palm to airplane and gun.

—Max Horkheimer1

Radio, the first abuse, [led] from World War I to II, rock music, the next one, from II to III.

—Friedrich Kittler2

In August 1939, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer released The Wizard of Oz, a film that showcased the technological advances in cinematography and spoke to the power of film in the modern age.3 Known for its introduction of Technicolor to audiences around the world, The Wizard of Oz draws attention to its achievements in the visual medium through the inclusion of such self-reflexive objects as the Wicked Witch of the West’s crystal ball and the doorframe of Dorothy’s Kansas home. But it is what you cannot see in this iconic film that hints at the undertones of violence throughout the movie and the tumultuous inter-war period from which it emerged. Despite being a significant film about sight, The Wizard of Oz is also a film about sound, in particular radio sound,4 and it is in these sonic moments that the violence of the early twentieth century materializes.5 Although this technically superior film offered audiences a distraction from thoughts of the coming war and the breaking news reports heard daily over the radio, it also subtly reconfirmed the historical relationship between radio and war, which had emerged from the military’s use of the medium in World War I. It is this relationship that media critic Theodor Adorno and radio legend Orson Welles emphasize in their radio writings, both critical and fictional. As a brief look at The Wizard of Oz will illustrate, the connection between radio and war was so ingrained in the American public’s mind that the references to radio went largely unnoticed. However, as I discuss in this chapter, it is the comparable violence of radio industry standardization and fascist government control, alongside the historical association between radio and war, that haunts the radio and culture industry writings of Adorno and encourages Welles to panic a nation.

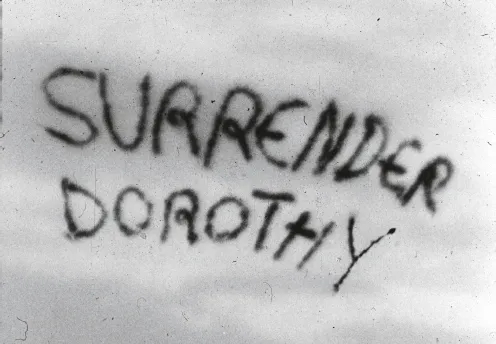

The first notable instance of war and radio’s conflation in The Wizard of Oz comes once Dorothy, along with her dog Toto and her newly acquired friends (Scarecrow, Tin Man, and Cowardly Lion) arrive at the Emerald City in an attempt to “see the Wizard,” who has, they are told, never before been seen. Before they can receive an audience with the great and powerful Oz, however, the Wicked Witch of the West appears and writes the words “Surrender Dorothy” in the sky with her broom. In this cinematic moment, the Wicked Witch of the West achieves more than simply issuing a warning to Dorothy, thereby setting into motion her own eventual demise; the Witch also physically enacts what radio essentially is: language on the air. And the message the Witch chooses to write, or rather send, on the air is none other than one of war, emphasized by the bomber-like trail of smoke in which it is written. This message reaches a vast Emerald City audience, and, unlike cinema (which required public viewing) and television (which was still in its infancy), could reach attentive citizens in their homes. Yet this image of war on the air, which leads to mass panic in the Emerald City, is not the only portrayal of radio and war’s conflation in the film.6 Once Dorothy meets the Wizard, we witness the true power of radio in a time of conflict.

When Dorothy and the other weary travelers first meet the great and powerful Oz, he is a green gaseous face flickering in and out like a bad visual transmission and positioned over a giant throne. At times, he is only a voice booming like artillery through the flames and red smoke. The Wizard is certainly meant to remind us of the voice of God (for he is indeed “great”) and his voice coming through the flames conjures up an image of God speaking as a burning bush to Moses (another weary traveler). But the Wizard’s phantasmal image and actions are also reminiscent of the devil speaking out of a pyrotechnic hell, a Faustian Mephistopheles promising his travelers their hearts’ desires. The Wizard uses his powerful acousmatic voice (what we later realize is created by a radio-like device) to command, or rather to blackmail, Dorothy into battle.7 In order to have their wishes granted, the friends must retrieve the broom of the Wicked Witch of the West, and, as the Tin Man points out, the only way to succeed in this mission is to kill the Witch.

Figure 1.1: “Surrender Dorothy”

And, of course, kill the Witch they do, with the help of a little bucket of water. Upon returning to the Emerald City with the Witch’s broomstick in hand, the travelers make a startling discovery—the Wizard is no more than a technologically savvy man behind a curtain. It is evident that the Wizard is operating a ruse from a radio booth, complete with flashing lights, dials, and a 1930s microphone. Thus it was not God, or the devil, or even a green vaporous head that ordered Dorothy into battle; it was a man and his radio voice. The magic of radio is disclosed in this film—the man behind the curtain (or the radio station) is revealed. It is in this scene that the two-fold relationship between radio sound and sight is demonstrated. At first, the green head surrounded by fire intensifies the message of the Wizard’s booming voice, but, as the exposure of the “real” Wizard reveals, this cooperation of sight and sound is a fiction. Instead, tension exists between the aural and visual mediums as the Wizard in human form fails to match his own powerful voice.8

My choice to introduce the opening chapter of a book on radio by way of an extended radio-centric reading of a classic Hollywood film might seem out of place. But my analysis of The Wizard of Oz shows that the connection between radio and war was so prevalent by World War II that movie-going audiences accepted without comment this correlation, one not included in L. Frank Baum’s original The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900). Perhaps this is because in 1939 radio was the central communications medium, and when one thought of a booming voice leading a people or commanding an army, movie-going audiences naturally thought of radio that was, at this time, filled with the voices of numerous politicians from Roosevelt’s relatively innocuous “fireside chats” to Hitler’s fascist diatribes.9 These small but crucial moments in The Wizard of Oz illustrate the significance of radio in the early twentieth century, not just as a source of entertainment (the film is meant to be enjoyed), but also as a public service (the Wizard grants the travelers’ wishes), a news source, and a mouthpiece for war. For 1930s radio listeners, there still existed a cloak of mystery and magic around the radio voice that came over the air and into their homes every day without fail. This mystery and reliability lent the new medium a sense of authority that other media (newspapers and cinema) lacked, a uniqueness that was not lost upon radio networks such as the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) and the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), the latter of which referred to radio as “magic[al],” a “Genii” that is here to grant the listeners’ every wish.10 But while major broadcasting networks and their advertisers worked to capitalize upon the naiveté of its listening audience, radio critics and writers in the U.S. attempted to call attention to the smoke and mirrors that kept the American public from participating more astutely with the new medium.11

Yet for all the entertainment, culture, education, advertising, and politics that American radio had to offer in the late 1930s and early 1940s, it was radio’s reports of war, so colorfully brought to life in The Wizard of Oz, that kept Americans listening. Theodor Adorno, a German–Marxist intellectual who fled Europe for the United States in 1938, also could not help but be captivated by the news about the war. He experienced firsthand the power of the radio, as Hitler and the German fascists used the medium to help indoctrinate the German population throughout the 1930s. Although best known for his dialectical materialism and his work on the culture industry, Adorno’s years in America were also spent analyzing the radio and its programming. While his radio writing is becoming increasingly known and discussed, critics have often overlooked the strong ties Adorno’s radio work has to his experience of fascism and the war. The war, I argue, informs his opinion of radio, and, in particular, his critical response to Orson Welles’ broadcast of The War of the Worlds. In this chapter I re-examine Adorno’s writings on radio, showing how his criticisms of the new mass communications medium are grounded in the chaotic historical time in which he is writing. I pair this discussion of Adorno with perhaps the single-most famous American radio broadcast, Welles’ The War of the Worlds, in order to illustrate the dangers Adorno perceived in radio.12 This broadcast, which caused a nation to panic, did so largely because of the troubles in Europe, and, as will be shown, just as Adorno’s radio work was informed by global conflict, so too is Welles’ play mired in references to fascism’s advance, suggesting that even at the height of nationalist movements, authors were responding to transnational concerns within their work.13

Radio’s fascism and the violence of the voice

Adorno is often depicted as a kind of Wicked Witch of the West for mass communications, a characterization that is not without footing. Like the Witch, Adorno wrote (and spoke) “on the air,” issuing a warning to all those who would pay heed. From his metaphorical home in an ivory tower, Adorno, like the Witch from her grey castle, casts aspersions on those below. In particular, the Witch sets her sights on the fun-loving, all-American Dorothy, who dances her way through Oz singing catchy tunes, including one titled “The Jitterbug.” Although cut from the final film, it is not hard to imagine Adorno including “The Jitterbug,” with its quick, steady beat and American slang, among his list of standardized music examples and criticizing it as cultural rubbish, or “canned food” as he called it, right alongside jazz and other popular musical forms. My playful comparison of Adorno and the Witch is meant to highlight a misconception within the American academy that paints Adorno as a scholarly curmudgeon and European snob. In the classroom he is often used as a foil to Walter Benjamin, who has been embraced by cultural and media theorists alike for his largely revolutionary view of cinema technology in “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Adorno, on the other hand, is dismissed for being critical of jazz and for stating of film that “Every visit to the cinema leaves me, against all my vigilance, stupider and worse.”14

Yet an extreme statement on the cinema and hasty interpretations of Adorno’s theories about jazz should not discourage investigation into his media work, as his oeuvre is filled with essays and books on everything from the gramophone to radio, cinema to television.15 During his on-and-off residence in the United States from 1938 to 1953, Adorno produced an abundance of work on media culture, specifically the film and radio industries. Given Adorno’s frequent criticism of the culture industry in his essays and, in particular, Dialectic of Enlightenment, it is not surprising that he has been categorized as a cultural snob, or, as Andreas Huyssen writes, “the theorist par excellence of the Great Divide.”16 But this image of Adorno has also led critics to ignore the historical factors contributing to his media assessments and overlook his involvement in the institutions of the very media forms he critiqued.17 He is reported to have been “fascinated by the illustrated episodes ‘from the Edgar Bergen/Charlie McCarthy radio programmes’” and while in Los Angeles he involved himself in Hollywood, enjoying the company of a fellow exile, director Fritz Lang, and such big-name stars as Charlie Chaplin.18 Far from making Adorno “stupider,” the cinema and the radio were in fact the fodder for his work. Rather than residing in an ivory tower, a more accurate depiction would show Adorno working from below in an attempt to topple the growing empires of the biggest media industries in the world.

Although his interest in musical culture was well established by the time he reached New York in February 1938, it is Adorno’s residence in the United States that sparks a bevy of writings on the radio industry; this is in part due to his employment at the Princeton Radio Research Project (PRRP), which was directed by the sociologist Paul Lazarsfeld along with the famous psychologist Hadley Cantril and the former research director for CBS, Frank Stanton.19 Due to his extensive musical knowledge, Adorno was hired as the director of the music division to work on a project entitled “The Essential Value of Radio to All Types of Listeners.” The purpose of this project and the Institute on the whole was to use empirical research in order “to discover the role of the radio in people’s everyday life, the motives underlying their listening habits, the types of programmes that were popular and unpopular, and whether groups of listeners could be targeted by broadcasts specifically aimed at them. What stood at the centre of attention was the need to establish data that could be of use to administrators.”20 Understandably, this type of research did not sit well with Adorno, whose European theoretical approach did not meld with Lazarsfeld’s empirical model.21 What made the research even more distasteful to Adorno was the fact that the PRRP was funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, which, as part owner of NBC, was far from an unbiased donor. Despite these difficulties, Adorno threw himself into his new research, producing four essays on radio while at the PRRP; these included “The Radio Symphony,” “A Social Critique of Radio Music,” “On Popular Music,” and “Analytical Study of the NBC Music Appreciation Hour.” After the music division was cut from the PRRP, in part because the Rockefeller Foundation felt that Adorno’s theoretical reports had no utilitarian value, Adorno was hired by the Institute for Social Research. And in November 1941, he left the East Coast, journeying West to join Horkheimer and other Frankfurt School associates already in Los Angeles. It is here that Adorno wrote his famous essay on the culture industry for the collaborative work Dialectic of Enlightenment, synthesizing both his suffocating experiences with the radio industry and his opinions of an ongoing and catastrophic war.

For Adorno, culture, including media culture, was shaped by what he and Horkheimer termed the “dialectic of enlightenment.” Using this term as the title for their famous 1947 study of Western civilization, the two theorists question the linear narrative of Marxism and instead offer an alternative conception of history whereby the brutalities of fascism arise from democracy and the rationalism of the Enlightenment. The result being that the values of the Enlightenment are turned upon their heads. In Germany this extreme rationali...