![]()

He who knows no other language does not truly know his own.

(Goethe, in Vygotsky, 1962: 110)

KEY TERMS

| Mother tongue | A term subject to much debate and sometimes referred to as home/heritage/community or first language. Definitions include: the language learnt first; the language known best; the language used most; the language with which one identifies; the language one dreams/thinks/counts in; and so on; none of which are acceptable to all. It is generally recognized that a mother tongue may change, even several times during a lifetime. |

| New language learner | A child who is at an early stage or who still lacks fluency in a second or additional language but whose ultimate aim is to become as fluent as possible, that is, able to communicate easily with others in the language and able positively to identify with both (or all if more than two are being learned) language groups and cultures. |

| Emergent biliterate | A child who is learning to read and write in more than one language simultaneously. |

| Metalanguage | A term in linguistics for language used to talk about language. Research studies show that young bilinguals have an advanced metalinguistic awareness as they are able to realize the arbitrariness of language, see word boundaries, and so on at an earlier stage than monolinguals. |

| Grammar | A description of a language; an abstract system of rules in terms of which a child’s knowledge of a language can be explained. |

| Orthography | The principles underlying a spelling or writing system. |

Annie is 7 years old and beginning her second year of primary school in Thailand. From time to time she escapes the crowded city of Bangkok to stay with her extended family in the countryside. Eventually, she hopes to live in Britain where she has relatives. She has already learned to read simple texts in Thai, her mother tongue, and loves to practise these with her mother at home. Like many young children in schools across different continents, Annie is also beginning to learn to read and write in English, a language chosen by many countries as a necessary asset for the education of all young children as they start school. Other children across the world will be learning in different languages, often the one that is politically dominant in the country in which they live. Some will be the children of refugees, others of economic migrants, others from indigenous families whose mother tongue is not the official language of the school and yet others from multilingual countries where children will be expected to become literate simultaneously in more than one language. Like many children across the world, Annie will need to learn that the new language will have a different script and very different rules from her own. Gradually, through becoming a reader in English, Annie will learn to make sense not only of new words but of other worlds, with very different customs, traditions and stories from her own. The aim of this book is to show how young children undertake the task of learning to read in a new language at school or at home and to argue that children like Annie have distinct strengths and weaknesses not explained in monolingual perspectives on early literacy. Later chapters will introduce Julializ from the USA, Pia and Nicole from France, Ah Si from Macau-Sar, China, Elsey from Australia, Sanah from Singapore and Dineo from South Africa as well as children from Britain. Although they will all be learning in very different cultural contexts, I shall draw out common patterns that hold these children apart from their monolingual peers. The book thus suggests principles and practices for all those interested in observing the learning of young new language learners and for those engaged in initiating them into new words and worlds.

In this chapter, I begin to outline the nature of the task through the example of Annie reading in both Thai and English. Annie is lucky, since her mother has enjoyed telling and reading stories to her since she was very small. She is now trying to find dual language Thai/English stories for her to read and finds Elephant, a traditional Thai fable.

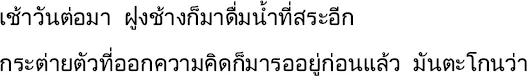

Annie first reads the story with her mother in Thai. Afterwards, she reads the story again in English with a native English speaker. Looking closely at Annie’s reading in both languages, we begin to perceive some of the differences between reading in a first and a new language, as well as the complexity of tackling a text in a language one cannot fluently speak. Since this book is written for English rather than Thai speakers, we can only dissect her achievements in Thai through the English language. However, the grammatical structure and rules of Thai are very different from English, as we shall see later in the chapter.

The animal story – Elephant

A herd of elephants wandered to search for a pond. Finally, they found one. (p. 1)

The elephants stepped on the soil around the pond which was the rabbits’ shelter. This killed many rabbits. (p. 2)

When many rabbits died, the rest of them discussed the problem. A rabbit said, ‘I have an idea. I will tell the elephants that I am the rabbit of the moon, and the moon forbids anyone to drink water from this pond.’ (p. 3)

The following morning, the herd of elephants came to drink water in the pond. The rabbit who had the idea arrived before the elephants. He shouted … (p. 4)

‘You elephants, I am the rabbit which is on the moon. I convey the moon’s words to all of you. He forbids any animals to swim or drink water in this pond. Anyone who ignores his words will be killed.’ (p. 5)

The elephant’s leader which was very foolish believed the rabbit.

‘Thank you very much for your kindness. We have made a mistake. We hope the moon will not punish us,’ he pleaded with the rabbit. (p. 6)

‘Where is the moon now? Please bring me to see him. I would like to apologise to him.’ ‘He is taking a bath in the pond. I will bring you to see him right now,’ the rabbit replied and went ahead. (p. 7)

When they arrived at the pond, it was at dusk. The shadow of the moon reflected in the water. The rabbit pointed at it and said, ‘Pay respect to him then hastily go away.’ (p. 8)

The elephants’ leader gradually lifted his trunk to touch his head to pay respect to the moon. Then the elephants went away and never came again. (p. 9)

Figure 1.1 An illustration from The Elephant

Let us look first at what Annie can do in Thai after just a year of learning to read. Although both the story of Elephant and the book itself are new to Annie, she sets to reading confidently in Thai to her mother, holding the book herself and turning each page appropriately. As usual, her mother reads the first word on the page and Annie continues. Her reading appears fluent and effortless and she reads with obvious enjoyment. Her eyes search the illustrations for information and she comments on animals in the pictures as she goes along. But what is Annie actually able to do as she tackles the text? Through the dual-language version, we see that she successfully reads 19 different nouns (herd, elephants, rabbits, moon, pond, soil, shelter, problem, idea, water, morning, words, animals, leader, kindness, mistake, dusk, shadow, trunk), 30 different verbs (wandered, found, search, stepped, killed, died, discussed, said, have/had, tell, am, forbids, drink, came, arrived, shouted, convey, swim, ignores, pleaded, bring, apologise, replied, went, reflected, pointed, pay respect to, lifted, touch), nine different prepositions (on, around, of, from, in, before, ahead, at, away from) as well as a limited number of pronouns, adverbs and adjectives. Had she been reading in English, she would have read 22 verbs in the past tense, seven in the simple present and one each in the present continuous, the future and future passive as well as future conditional, and the present perfect tenses, infinitives and the imperative form. She uses prepositions of place, time and motion. Additionally, Annie obviously understands the content of the story and she is able to empathize with the characters. When questioned, after reading, on what she likes about the story, she replies confidently: ‘the rabbits … because they are clever’.

In fact, Thai is very different from English and there are, consequently, a number of language-specific grammatical and orthographic rules that Annie has already learned. Although the intention here is not to describe in detail the Thai language and script, a few aspects are important to understand the task Annie faces of becoming bilingual and biliterate in her first and her new language. First, we see that she is already becoming a competent user of the Thai script, an Indic alphabet originally designed to represent the sounds of Sanskrit but with new symbols created during the thirteenth century to represent the sounds of Thai (Hudak, in Comrie, 1987). The script is by no means an easy one to learn. Thai is a tonal language with five different tones (low, high, falling, rising and mid-tone) with several symbols for the same sound. There are 44 consonants divided into three groups (high, mid and low) to indicate the tone in spelling, a complication when learning to read, as well as 18 vowel sounds. As in other tonal languages, for example Mandarin and Cantonese, use of the correct tone is crucial since reading a word or sentence using the wrong tone will entirely change its meaning. There are other aspects that make both spoken and written Thai very difficult – the Thai themselves regard their language as complex and stratified, even for highly educated people. Central to this is the proliferation of titles, ranks and royal kin terminology that has affected various aspects of the language. The choice of pronouns, for example, is highly complex. In contrast to a simple ‘I’ and ‘you’ in English, Annie will need to choose according to the sex, age and social position of herself and the addressee as well as her attitude or emotion towards the person at the time of speaking. She will later need to begin to learn elaborate, often ryhming, expressions. However, other aspects might make both spoken and written Thai easier to contend with than English. There are no articles (‘a’, ‘an’, ‘the’, for example) to distinguish between and no inflections for case, gender or number of nouns – these are indicated by either affixes (prefixes or suffixes), compounding (‘parents’ = ‘father’ and ‘mother’), reduplicating (‘dek’ or ‘child’; ‘dekdek’ or ‘children’) or repeating a word with the same word one tone higher in pitch than the normal tone, an effect usually used by women. Verbs also have no inflection for tense or number which are shown either by the context, an added time expression or a preverb, often showing that the action begun by the main verb has been completed. Finally, even a non-Thai reader may discern from the text above that, orthographically, there is no space between individual words; a space is used to denote the end of a sentence rather than a full stop. This very brief glance at the Thai language and script begins to highlight what Annie, like many young children, has achieved as she speaks and reads in her mother tongue by the end of her first year of school.

The task ahead: new languages, literacies and scripts

The child assimilates his/her native language unconsciously and unintentionally but acquires a foreign language with conscious realisation and intention … the child acquiring a foreign language is already in command of a system of meaning in the native language which s/he transfers to the sphere of another language. (Vygotsky, 1935, in John-Steiner, 1986: 350)

Reading in English, a language Annie is learning formally in school and beginning to learn informally with her mother, is a very different matter. A text she manages confidently in Thai is clearly too difficult in English and Annie looks expectantly to the native English speaker (a relative she trusts, yet sees and speaks to very rarely) for help. Instead of holding the book herself, she hands over to the adult to take control and to turn the pages. Eavesdropping on Annie and the adult reading together begins to provide a window onto the strengths and weaknesses of a young child as she embarks on the task of learning to read in a new language:

| Annie: | I can’t read English. But I can read ‘b’, ‘d’, ‘c’ and ‘1, 2, 3, 4, 5,... |