![]()

People think I’m successful. I’m well paid, have a nice house and I’m good at my job. But I feel more and more dissatisfied with what I do.

I can’t take a year off. How will it look on my CV? Employers will think I’ve been wasting my time.

Everyone’s telling me I’ve got a lot of potential; but I’ve lost interest in studying.

When I married Sam, I thought he would be such a good provider. Now he’s been made redundant.

The key words in these statements – successful, wasting, potential, provider, redundant – reflect a valuing of success and achievement. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that many people who approach a career counsellor, influenced by this pressure to succeed, may feel to some degree a failure in the eyes of partners, peers, employers or parents.

These assumptions, influences and values raise a number of considerations for career counsellors. Clients may want to turn their feelings of failure into a successful solution fairly urgently – to put things right, to find the right career, to feel all right. Their need to get things right may be transferred into expectations of the career counselling process to come up with the right answer, and to focus on extrinsic aspects of job satisfaction, such as money, status and working conditions, rather than considering their personal strengths and weaknesses.

Additional external pressures, such as keeping up the mortgage payments, saving face with friends or getting into the best college course tend to discourage clients from addressing any personal, and perhaps painful, emotional issues. These include understanding, accepting and building on changes in personal values, and coping with any negative feelings such as the loss and anger so often felt after losing a job.

What is career counselling?

Many people, if asked to define career counselling, would probably opt for something resembling the approach proposed by Parsons, as long ago as 1909. He wrote:

In the wise choice of vocation, there are three factors.

- A clear understanding of yourself

- A knowledge of the requirements and prospects in different lines of work

- True reasoning on the relations of these two groups of facts.

This approach is based on the measurement, through testing, of the client’s aptitudes and interests, followed by a recommendation by an ‘expert’ on occupations which provide a match in terms of the aptitudes and interests required. This process of ‘talent matching’ (sometimes known as the ‘test and tell’ approach) was the predominant form of assistance available to people seeking career help until the 1960s. For a number of reasons, we believe that career counsellors should not accept their clients’ demands and expectations for ‘advice on the best career’.

Firstly, making appropriate occupational decisions calls for the assistance of skilled and sensitive counselling: to reach the point where a rational decision can be made, emotional issues such as managing relationships, coping with loss and change and recovering from damaged self-esteem may first have to be addressed.

Secondly, since a ‘job for life’ is no longer a reality, lifelong decision-making skills are more conducive to the continuing challenge of making appropriate life and occupational choices, which are themselves increasingly interdependent.

Thirdly, employers require an increasingly flexible approach to their changing requirements, expecting employees to take responsibility for managing their own development, which might mean creating or accepting a ‘development opportunity’, such as a secondment, rather than waiting for promotion. There is also an increasing recognition that individuals themselves progress through a number of life stages (Super, 1980) and changes in their role requirements and responsibilities (Herriot, 1992).

Fourthly, making decisions is very much a matter of personal responsibility. A counselling approach empowers people to take such responsibility where they, not the counsellor, are the ‘expert’.

The career counsellor, like all other counsellors, provides time, support, attention, skill and a structure which enables clients to become more aware of their own resources in order to lead a more satisfying life. We see career counselling as a process which enables people to recognise and utilise their resources to make career-related decisions and manage career-related issues. Although focusing on the work-related part of a person’s life, it also takes into account the interdependence of career and non-career considerations.

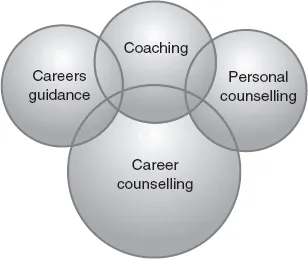

This book focuses on the practice of career counselling. Figure 1.1 illustrates the overlap of career counselling with personal counselling, careers guidance and coaching. The larger ‘Career counselling’ circle indicates that the focus needs to remain on the career aspects of the client’s life and the approach is primarily one rooted in counselling.

‘Coaching’ means different things to different people. People coming for career counselling are often unclear about their career direction. Coaching aims to enable people to become more effective in their current careers. There is overlap, but there is also a distinction.

In 1991 Hawthorn described ‘guidance’ as ‘help for individuals to make choices about education, training and employment’. Today, the terms ‘advice’ and ‘information’, as well as ‘guidance’, are as commonly used to describe what careers services offer to potential users. We see this as a positive sign, being a move away from the directive and prescriptive connotations of the term ‘guidance’. The activities of those involved in providing information, advice and guidance will involve counselling, as well as coaching, teaching, assessment and advocacy.

Figure 1.1 How career counselling overlaps with other forms of help

In addressing personal concerns regarding redundancy, retraining, relocation, retirement, relationships at work, promotion, career breaks and stress, career counselling necessarily overlaps with personal counselling.

The provision of career counselling in the UK

Unfortunately, in England the provision for adults seeking career help is very fragmented and largely uncoordinated. There is provision over much of the country, but it is not easy for anyone needing help to know what is on offer and who it is available for. It is unlikely that trained career counsellors staff the services. The Learning and Skills Council (LSC) is the national funding body for adult information, advice and guidance (IAG) throughout England. Local services vary from area to area, as services are delivered via IAG partnerships in each local region. IAG partnerships can include, for example, higher and further education careers services, voluntary bodies, private-sector providers and unions. There is no standard answer to how much services cost, or indeed whether they are free. Eligibility, too, varies, as some services are open to anyone, whilst others cater for those up to a certain level of qualification.

The national initiative ‘Jobcentre Plus’ is being created to integrate job centres, which give job advice, with benefits provision, by 2006. ‘Learndirect’ offers advice and information on education and training courses and is available to all nationally via the world wide web and telephone. ‘Learndirect-futures’ has online tools for career choice, as well as access to advisers. ‘Waytolearn.co.uk’ has been developed by the DfES to bring together information for people who want to learn (see Appendix C).

Help for young people in making career decisions is offered by careers teachers in schools and professionally qualified staff employed by the local Connexions partnership or careers service. In England, the ‘cut off’ age between services for young people and adults is 19, whereas in Scotland, for example, an integrated service is available to people of all ages.

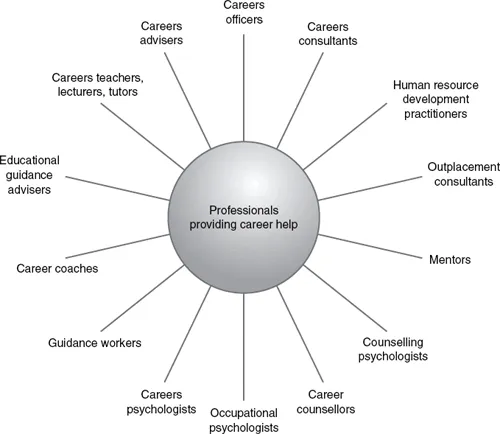

Figure 1.2 Who provides career help?

The various professionals involved in helping others to face career dilemmas are shown in Figure 1.2. All UK public universities provide a free careers service for their current students. Some also provide services to students once they have left, for which fees are usually charged. The University of London has a fee-charging careers service – C2 – available to any graduate, and at any stage of their career. For a more detailed study on careers services for employed people, see NICEC (2001).

The Department for Work and Pensions has ‘Programme Centres’ which offer the ‘New Deal’, a programme providing job search sessions, access to the internet and CV support, usually for a 13-week programme. Access is normally restricted to those unemployed for at least six months. Some services, known as ‘Gateways’, are available for people unemployed for less than six months.

An increasing number of employers offer career help to their staff, for example:

- career development discussions to clarify career direction and/or development plans;

- workshops for ‘high potential’ people to assess and reflect on their suitability for general management or partnership;

- career support for specific groups, such as graduates, women or ethnic minorities;

- career management ‘centres’ or ‘clinics’, available for all on a confidential basis;

- learning and development advice, information and counselling, to support career development;

- outplacement help with job hunting for people whose jobs are being made redundant;

- career counselling for ‘redeployees’ at a time of restructuring;

- pre-retirement planning services;

- advice, information and self-assessment exercises via an Intranet site; and

- coaching and mentoring.

See Chapter 7, Career Counselling in Organisations, for a more detailed look at this area. See also the NICEC report (2004) on managing careers in large organisations.

Some national organisations, for example, the Armed Forces, the Law Society, the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors, the Institute of Public Relations and the Royal National Institute for the Deaf, also offer career help to special groups.

Because government-backed career counselling provision for adults in the UK continues to be so fragmented, there has been a mushrooming of independent services, staffed by specialist career counsellors, occupational psychologists and counselling psychologists. These services differ in their use of psychometric tests. There are some services which still offer a ‘test and tell’ approach, in which the client is given a series (or ‘battery’) of tests measuring aptitudes, occupational interests and aspects of personality, the results of which are then interpreted by a consultant psychologist and a report with recommendations subsequently written. Other career counsellors may make little or no use of tests, but use counselling skills to assist clients to make sense of occupational and other aspects of their lives. The connection between work and non-work life has increasingly become the focus of anyone helping adults with career dilemmas, whether it be the burnt-out executive who wants to spend more time with the family or the single mum trying to make ends meet.

Outplacement consultants offer specific help to executives and others facing a job loss. This may involve some counselling to assist recovery from the trauma of the redundancy, but more usually focuses on coaching and support in job hunting. Such services are often paid for by the company as part of a severance package. Outplacement companies are now broadening their services to include career reviews and career-planning workshops, although the traditional job search activities remain the core of what they offer. They are also increasing the provision of services via the Internet, and setting up advisory centres ‘in-house’ for staff below executive level.

Confusingly, some practitioners who describe themselves as career counsellors are not doing career counselling in the sense that they subscribe to a counselling philosophy or have training in counselling skills.

Although traditionally offered on a one-to-one basis, career counselling is increasingly being offered in groups. There are a number of advantages of working in groups:

- they are economical to run;

- a group provides a wider range of resources, ideas and information;

- participants realise that they are not alone, as others are facing similar issues;

- mutual support is readily available both during and after the group’s existence;

- there is less dependency on the career counsellor as ‘expert’; and

- groups provide more opportunities to use active techniques such as coaching in job-hunting skills.

Many such groups are run within employing organisations, and may be focused primarily on occupational is...