![]()

PART 1

An Introduction to the Field of Contemporary Digital Technology Research

This book has been created to give the reader a good solid overview of digital technology research, in particular the methods and approaches that typify contemporary work. Our first two chapters give us an excellent foundation in that task, surveying the field of technology and examining research that focuses on the human uses, effects and challenges of the digital technology that so infuses our modern age.

Our first chapter, by Paul Ceruzzi, provides us with an historical foundation to this task – starting with the coining of the term ‘digital’ by the Bell Telephone Laboratories mathematician George Stibitz. As Ceruzzi points out, since then this term has come to describe much of the social, economic, and political life of the twenty-first century. Ceruzzi goes on to review how the particular features of computers – machines that stored, computed, and so on – developed out of wartime research. The German mathematician Zuse took the bold step of using theoretical mathematics to design computers, yet it was Alan Turing who took the opposite step – introducing the concept of a machine into mathematics. On these foundations, Wiener’s notions of cybernetics, and Shannon’s work in information theory provides the intellectual foundations for computer technology. Indeed, perhaps unusually, computers were theoretically specified before they were physically practical. Yet when they were built they slowly but steadily came to transform not only jobs of computation but also communication. Ceruzzi guides us through the advent of computing and networking, the World Wide Web, and, in turn, the ongoing connections between computing technology and social networking.

In contrast, our second chapter by Charles Crook engages more deeply with the digital technology research tradition, in particular social science research traditions. This lively chapter engages with a large body of work, yet focuses clearly on questions of how human social action is reconstituted in digital form – in particular in virtual worlds and augmented reality. Avoiding the description of digitization as amplification, the chapter engages with how human cognitive activity and social coordination come to the fore when studying digital technologies in use.

![]()

1

The Historical Context

Paul Ceruzzi

INTRODUCTION

In the spring of 1942, the US National Defense Research Committee convened a meeting of high-level scientists and engineers to consider devices to aim and fire anti-aircraft guns. The German Blitzkrieg had made the matter urgent. The committee noticed that the proposed designs fell into two broad categories. One directed anti-aircraft fire by constructing a mechanical or electronic analog of the mathematical equations of fire-control, for example by machining a camshaft whose profile followed an equation of motion. The other solved the equations numerically – as with an ordinary adding machine, only with high-speed electrical pulses instead of mechanical counters. One member of the committee, Bell Telephone Laboratories mathematician George Stibitz, felt that the term ‘pulse’ was not quite right. He suggested another term, which he felt was more descriptive: ‘digital’ (Williams 1984: 310). The word referred to the method of counting on one’s fingers, or, digits. It has since become the adjective that defines social, economic and political life in the twenty-first century.

It took more than just the coining of a term to create the digital age, but that age does have its origins in secret projects initiated during World War II. But why did those projects have such a far-reaching social impact? The answer has two parts.

The first is that calculating with pulses of electricity was far more than an expeditious way of solving an urgent wartime problem. As the digital technique was further developed, its creators realized that it tapped into fundamental properties of information, which gave the engineers a universal solvent that could dissolve any activity it touched. That property had been hinted at by theoretical mathematicians, going back at least to Alan Turing’s mathematical papers of the 1930s; now these engineers saw its embodiment in electronics hardware.

The second part of the answer is that twenty years after the advent of the digital computing age, this universal solvent now dissolved the process of communications. That began with a network created by the US Defense Department, which in turn unleashed a flood of social change, in which we currently live. Communicating with electricity had a long history going back to the Morse and Wheatstone telegraphs of the nineteenth century (Standage 1998). Although revolutionary, the impact of the telegraph and telephone paled in comparison to the impact of this combination of digital calculation and communication, a century later.

THE COMPUTER

Histories of computing nearly all begin with Charles Babbage, the Englishman who tried, and failed, to build an ‘Analytical Engine’ in the mid-nineteenth century (Randell 1975). Babbage’s design was modern, even if its proposed implementation in gears was not. When we look at it today, however, we make assumptions that need to be challenged. What is a ‘computer’, and what does its invention have to do with the ‘digital age’?

Computing represents a convergence of at least three operations that had already been mechanized. Babbage tried to build a machine that did all three, and the reasons for his failure are still debated (Spicer 2008: 76–77). Calculating is only one of the operations. Mechanical aids to calculation are found in antiquity, when cultures developed aids to counting such as pebbles (Latin calculi), counting boards (from which comes the term ‘counter top’), and the abacus. In the seventeenth century, inventors devised ways to add numbers mechanically, in particular to automatically carry a digit from one column to the next. These mechanisms lay dormant until the nineteenth century, when advancing commerce created a demand that commercial manufacturers sought to fill. By 1900 mechanical calculators were marketed in Europe and in the United States, from companies such as Felt, Burroughs, Brunsviga of Germany, and Odhner of Sweden (later Russia).

Besides calculating, computers also store information. The steady increase of capacity in computers, smartphones and laptops, usually described by the shorthand phrase ‘Moore’s Law’, is a major driver of the current social upheaval (Moore’s Law will be revisited later). Mechanized storage began in the late nineteenth century, when the American inventor Herman Hollerith developed a method of storing information coded as holes punched into cards. Along with the card itself, Hollerith developed a suite of machines to sort, retrieve, count and perform simple calculations on data punched onto cards. Hollerith founded a company to market his invention, which later became the ‘Computing-Tabulating-Recording’ Company. In 1924 C-T-R was renamed the International Business Machines Corporation, today’s IBM. A competitor, the Powers Accounting Machine Company, was acquired by the Remington Rand Corporation in 1927 and the two rivals dominated business accounting for the next four decades. Punched card technology persisted well into the early electronic computer age.

A third property of computers is the automatic execution of a sequence of operations: whether calculation, storage or routing of information. That was the problem faced by designers of anti-aircraft systems in the midst of World War II: how to get a machine to carry out a sequence of operations quickly and automatically to direct guns to hit fast-moving aircraft. Solving that problem required the use of electronic rather than mechanical components, which introduced a host of new engineering challenges. Prior to the war, the control of machinery had been addressed in a variety of ways. Babbage proposed using punched cards to control his Analytical Engine, an idea he borrowed from the looms invented by the Frenchman Joseph Marie Jacquard (1752–1834), who used cards to control the woven patterns. Whereas Hollerith used cards for storage, Jacquard used cards for control. But for decades, the control function of a Hollerith installation was carried out by people: human beings who carried decks of cards from one device to another, setting switches or plugging wires on the devices to perform specific operations, and collecting the results. Jacquard’s punched cards were an inside-out version of a device that had been used to control machinery for centuries: a cylinder on which were mounted pegs that tripped levers as it rotated. These had been used in medieval clocks that executed complex movements at the sounding of each hour; they are also found in wind-up toys, and music boxes. Continuous control of many machines, including automobile engines, is effected by cams, which direct the movement of other parts of the machine in a precisely determined way.

COMMUNICATION

Calculation, storage, control: these attributes, when combined and implemented with electronic circuits, make a computer. To them we add one more: communication – the transfer of information by electricity across geographic distances. That attribute was lacking in the early electronic computers built around the time of World War II. It was a mission of the Defense Department’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), beginning in the 1960s, to reorient the digital computer to be a device for which communication was as important as its other attributes.

Like control, communication was present in early twentieth-century business environments in an ad hoc fashion. People carried decks of punched cards from one machine to another. The telegraph, a nineteenth-century invention, carried information to and from a business. Early adopters of the telegraph were railroads, whose rights-of-way became a natural corridor for the erection of telegraph wires. Railroad operators were proficient at using the Morse code and were proud of their ability to send and receive the dots and dashes accurately and quickly. Their counterparts in early aviation did the same, using the radio or ‘wireless’ telegraph. Among the many inventions credited to Thomas Edison was a device that printed stock prices on a ‘ticker tape’, so named because of the sound it made. Around 1914, Edward E. Kleinschmidt combined the keyboard and printing capabilities of a typewriter with the ability to transmit messages over wires (Anon. 1977). In 1928 the company he founded changed its name to the Teletype Corporation. The Teletype had few symbols other than the upper-case letters of the alphabet and the digits 0 through 9, but it provided the communications component to the information processing ensemble. It also entered our culture. Radio newscasters would have a Teletype chattering in the background as they read the news, implying that what they were reading was ‘ripped from the wires’. Although it is not certain, legend has it that Jack Kerouac typed the manuscript of his Beat novel On the Road on a continuous roll of Teletype paper. Bill Gates and Paul Allen, the founders of Microsoft, marketed their software on rolls of Teletype tape. Among those few extra symbols on a Teletype keyboard was the ‘@’ sign, which in 1972 was adopted as the marker dividing an addressee’s e-mail name from the computer system the person was using. Thus to the Teletype we owe the symbol of the Internet age.

The telegraph and Teletype used codes and were precursors to the digital age. By contrast, the telephone, as demonstrated by Alexander Graham Bell in 1876, operated by inducing a continuous variation of current, based on the variations of the sound of a person’s voice. In today’s terms it was an ‘analog’ device, as the varying current was analogous to the variations in the sounds of speech. Like ‘digital,’ the term ‘analog’ did not come into common use until after World War II. During the first decades of electronic computing, there were debates over the two approaches, but analog devices faded into obscurity.

One could add other antecedents of telecommunications, such as radio, motion pictures, television, hi-fidelity music reproduction, the photocopier, photography, etc. Marshall McLuhan was only the most well-known of many observers who noted the relation of electronic communications to our culture and world-view (McLuhan 1962). Others have observed the effects of telecommunications: for example, how the photocopier democratized the process of publishing or how cheap audio cassettes helped revolutionaries overthrow the Shah of Iran in 1979. As mentioned above, nearly all of these antecedents were dissolved and transformed by digital electronics, sadly too late for McLuhan to apply his insights.

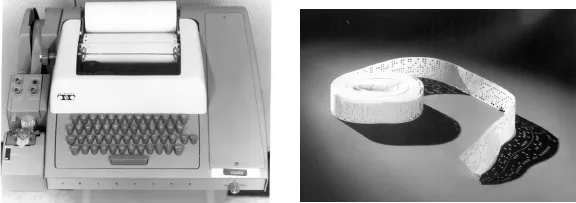

Figure 1.1 (Left) A Teletype Model ‘ASR-33’, a paper tape reader, which could store coded messages. Ray Tomlinson, a programmer at Bolt Beranek and Newman, says that he chose the ‘@’ sign (Shift-p) to delimit e-mail addresses because it was the only preposition on the keyboard. (Right) Teletype tape containing a version of the BASIC programming language, developed by Bill Gates and Paul Allen, c. 1975 (source: Smithsonian Institution photo).

DIGITAL ELECTRONIC COMPUTING

Before examining the convergence of communications and computing, we return to the 1930s and 1940s when electronic computing appeared. At the precise moment when the ensemble of data processing and communications equipment was functioning at its peak efficiency, the new paradigm of digital electronics emerged. We have already encountered one reason: a need for higher speeds to process information. That could be achieved by modifying another early twentieth-century invention: the vacuum tube, which had been developed for the radio and telephone. Substituting tubes for mechanical parts introduced a host of new problems, but with ‘electronics,’ the calculations could approach the speed of light. Solutions emerged simultaneously in several places in the mid-1930s, and continued during World War II at a faster pace, although under a curtain of secrecy that sometimes worked against the advantages of having funds and human resources made available.

The mechanical systems in place by the 1930s were out of balance. In a punched card installation, human beings had to make a plan for the work that was to be done, and then they had to carry out that plan by operating the machines (Heide 2009). For scientists or engineers, a person operating a calculator could perform arithmetic quite rapidly, but she (such persons typically were women) had to carry out one sequence if interim results were positive, another sequence if negative. The plan would have to be specified in detail in advance, and given to her on paper. Punched card machines likewise had stops built into their operation, signalling to the operator to proceed in a different direction depending on the state of the machine. The human beings who worked in some of these places had the job title ‘computer’: a definition that was still listed first in dictionaries published into the 1970s. This periodic intrusion of human judgment and action was not synchronized with the speeds and efficiencies of the mechanized parts of the systems.

THE DIGITAL CONCEPT

The many attempts to balance these aspects of computing between 1935 and 1950 make for a fascinating narrative. There were false starts. Some were room-sized arrangements of mechanisms that might have come from a Rube Goldberg cartoon. Others were modest experiments that could fit on a table-top. With the pressures of war, many attacked this problem with brute force. The following are a few representative examples.

In 1934, at Columbia University in New York, Wallace Eckert modified IBM equipment to perform calculations related to his astronomical research (Eckert 1940). He used punched cards for control as well as data storage, combining the methods of Jacquard and Hollerith. At the same time, Howard Aiken, a physics instructor at Harvard University, designed a machine that computed sequences directed by a long strip of perforated paper tape (Aiken 1964). Aiken’s design came to fruition as the ‘Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator’, unveiled at Harvard in 1944, after years of construction and financial support from the US Navy (Harvard University 1946).

Among those who turned towards electronics was J. V. Atanasoff, a professor at Iowa State College in Ames, Iowa, who was inve...