![]() PERSUASION

PERSUASION![]()

Propaganda and the Art of Lying

The noun “propaganda” makes people think of the verb “to lie,” because in the twentieth century “the big lie” was defined by the Nazi’s Ministry of Propaganda and Enlightenment. In his prison memoir, Mein Kampf (My Struggle), Hitler wrote, “[I]n the big lie there is always a certain force of credibility; because the broad masses of a nation are always more easily corrupted in the deeper strata of their emotional nature than consciously or voluntarily; and thus in the primitive simplicity of their minds they more readily fall victims to the big lie than the small lie, since they themselves often tell small lies in little matters but would be ashamed to resort to large-scale falsehoods.” He added, “It would never come into their heads to fabricate colossal untruths, and they would not believe that others could have the impudence to distort the truth so infamously.”

Propaganda Minister, Joseph Goebbels, made the theory into Nazi policy with these words: “Make the lie big, make it simple, keep saying it, and eventually they will believe it.”

The origin of propaganda was a little less onerous. The Congregatio de Propagand a Fide (Congregation for Propagating the Faith) was a religious order established by Pope Gregory XV in 1622 (later renamed by Pope John Paul II as the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples) to propagate Catholicism by missionaries the world over.

Centuries later, Edward Bernays, father of American public relations (and nephew of Sigmund Freud), wrote, “The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country.” Bernays was a master of manipulation. Advertising and propaganda went hand-in–glove: the practice of propagating the public’s faith in products or ideas by engaging them in a story, either real or imagined. In his 1928 book Propaganda: The Public Mind in the Making, he asserted, “If we understand the mechanism and motives of the group mind, it is now possible to control and regiment the masses according to our will without them knowing it.”

Bernays’s ideas about propaganda not only inadvertently influenced the Nazi ministry, but his storytelling fundamentals are present in what is called the “branding narrative.” Whether commercially or politically motivated, propaganda is not easily removed, in the public mind, from the idea of the big lie, and yet the public is propagandized daily in ways that are so nuanced that lies become truth. Tell a story convincingly enough and the malleable masses will be a faithful herd.

In the following examples the propaganda narrative intentionally enters the conscious and subconscious with predictable yet surprising consequences.

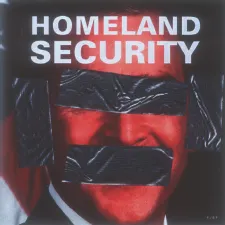

HOMELAND SECURITY AND ANTI-PROPAGANDA

After the 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, Americans were at their most vulnerable and susceptible to official decrees that promised to ensure their safety. The Patriot Act was signed into law that year, which gave the government extra powers to respond to terrorism. In 2002, Congress established the Department of Homeland Security. In 2003, the same Department announced that Americans should prepare for a biological, chemical, or radiological terrorist attack and assemble disaster supply kits, including duct tape and plastic sheets to seal doors and windows against nuclear, chemical, and biological agents.

Not surprisingly, it caused a surge in demand for duct tape. Given the evidence of anthrax and other bacterial materials sent through the US Mail, the threat appeared real. However, there also existed a healthy distrust of the government’s exaggerated prescriptions and politically dubious decrees. This anonymous guerilla poster turned the government narrative on its end by using the most recognizable images of the moment—the duct tape over President Bush’s mouth, eyes, and ears—painting a portrait of the President and Homeland Security authorities as being clueless in the face of threats, and compensating for that ignorance by issuing reports designed to scare the public.

PSY-OPS: LITTLE BLACK LIES

Paper bombs (leaflets and flyers) are the least sophisticated propaganda medium in the arsenal, but they can be incisive. Leafleting is the art of artlessness, designed to convey a straightforward message without artifice or conceit. There are the cautionary leaflets that offer an enemy combatant safe-haven and are targeted at the survival instinct. Then there are the ones designed specifically to undermine a battle-weary soldier’s morale, using lies and subterfuge to enter the conscious and subconscious.

This is especially virulent when aimed at exhausted troops who are more susceptible to doubt, despair, and free thought. Given the indescribable stress of battlefield encounters, after the initial adrenalin rush wears off, even the toughest veteran can be mentally vulnerable to any lies the psy-ops experts can dish out.

During the Cold War, when US troops were on constant alert, the Defense Department’s Psychological Warfare Division produced mock enemy leaflets, which were dropped during aerial maneuvers in an effort to teach troops that the harassing stories were fiction. These leaflets were dropped by the 505th Airborne Division (c.1955).

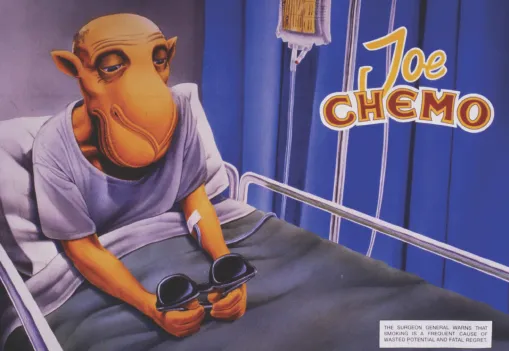

CAMEL CIGARETTES: SMOKE SIGNALS

During the late 1980s and into the early 2000s, the RJR Nabisco Company saturated American media with its Camel cigarettes "Smooth Character" campaign. The original Camel trademark—a gritty pen and ink rendering done in 1913 of Old Joe, a dromedary owned by the Barnum and Bailey circus—had considerably more charm than the updated anthropomorphic play-beast seen here. The trade character who peers off massive billboards and thousands of deli counters is what one advertising critic refers to "as moron fodder that is so much a part of life that if we are not careful, we forget to be insulted by it.”

This story is best illustrated by a 1990 open letter to Louis V. Gerstner, RJR Nabisco’s chief executive officer, from Mark Green, who was then the New York City Commissioner of Consumer Affairs: “As the father of two young children, I am appalled at your . . . campaign, which risks addicting children to cigarettes.”

Joe Camel does things most adolescent boys dream about—gets the girls, drives neat sports cars, and flies fighter bombers. The characters are rendered in an ambient, airbrushed cartoon style, and have metaphoric attributes similar to those of the popular Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. The human characteristics and expressions, while seemingly unthreatening, seductively hypnotize the younger viewer into believing he's a pal. The Marlboro man speaks to a post-adolescent need for machismo; it is not aimed at kids in the same way. But this cocksure camel would be neutered if not for a brilliant, if sinister, marketing strategy that made it ubiquitous.

When it launched the “Smooth Character” campaign in the United States, RJR Nabisco sought to recapture its faltering market share, but even the cleverest advertising ploy must ultimately fail when the product kills the conscripted, as this piece of anti-Camel propaganda aptly illustrates.

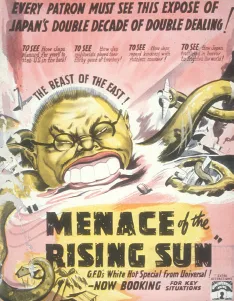

RACIAL HATRED: BLOOD STORY

“Otherness” is a euphemism for “not like us,” “alien scum,” “dirty stinkin’ . . . ,” or as the Nazi motto goes in the periodical Der Stürmer, “The Jews Are Our Misery.” Whatever the reasons for hate, racist propaganda that selects—or in today’s parlance, profiles—some group or individual for persecution follows similar narratives and plotlines throughout history. The offending racial, ethnic, or religious group is portrayed as “sub-human,” “parasitical,” or “bestial,” all of which is substantiated by drawn or photographed stereotypes and caricatures that emphasize the ugliest physical characteristics and evilest behaviors imaginable. In Germany, the story about the Jews situated them as an elite class that profited off the misery of the post-war German population—traitors who sold the nation into ignominy for personal financial gain. Meanwhile, the poor Eastern European Jews were equated with vermin that multiplied and spread disease—in Nazi terms, a cancer that had to be eradicated.

In the United States the propaganda was no less venomous, just aimed at a different target. With America at war with Japan, it was incumbent upon propagandists to draw portraits of monstrous creatures void of human emotion but full of a lust for Americans’ blood.

The Office of War Information, in Washington, D.C., created many of the grossly distorted depictions that were transmitted through media to civilians at home and to soldiers overseas. Civilians had to be constantly reminded of the ruthlessness of the enemy, while soldiers had to be encouraged to kill them without remorse. This was only accomplished through relentless dehumanization—the ends justified abominable graphic means.

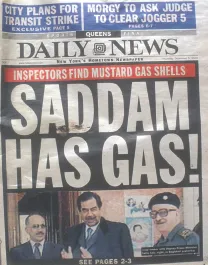

WEAPONS OF MASS DESTRUCTION

Propaganda is the art of making a small truth into a big lie. In 2002, before the United States invaded Iraq in 2003, propagandists were promoting the idea that Saddam Hussein was stockpiling lethal weaponry, notably biological and chemical agents. US Defense Secretary, Donald Rumsfeld, had helped Hussein build up his arsenal of deadly weapons a few years earlier. But as early as 1987 the Iraqi strongman clearly used chemicals against Kurdish people in the north of his country.

The propaganda war was launched against Saddam almost immediately after he announced plans to invade Kuwait in 1991, which he said had stolen petroleum from Iraqi fields. The Gulf War was fought to free Kuwait from a brutal occupation and the propaganda justifying an invasion was pervasive. Fought almost entirely with “smart bombs,” Saddam quickly lost the ground war. While his retreat allowed him to retain his elite Republican Guard and much of his equipment, he was sanctioned by the UN and forced into destroying his chemical and biological weapons. Although UN monitors were repeatedly kept from reporting on the destruction of these weapons, apparently Saddam had markedly reduced his stockpile to insignificant numbers. Yet by 2003 saber rattling in Washington focused on Iraq’s buried weapons of mass destruction. This prewar front page of the New York Daily News might well have been government propaganda. The double entendre of the headline humorously masks the subtitle of the real story: “Inspectors Find Mustard Gas Shells.” No one denied Saddam used chemicals in the past, but after the allied victory, no one could find any actual weaponry either.

![]()

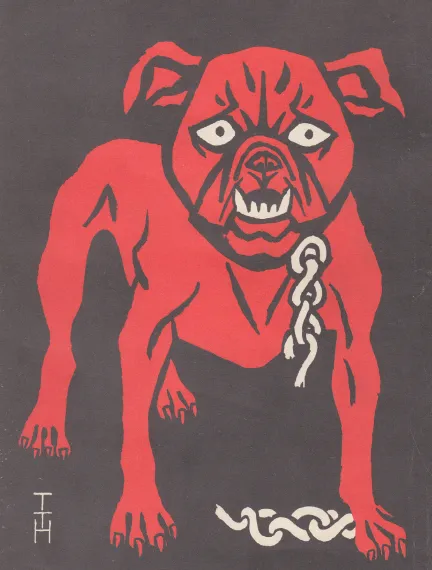

Simplicissimus Poster

THOMAS THEODORE HEINE

A red bulldog stares menacingly through stone-cold white eyes. A broken chain hangs from its neck. With sharp, spiky teeth it eagerly waits to attack unsuspecting fools, nitwits, and government buffoons.

Beware! This is not just some rabid canine, but the most unyielding watchdog ever conceived. Born not of flesh and blood, but of ink and brush, this bulldog was the embodiment of a nation’s anger, the charged graphic emblem of Simplicissimus, one of the most biting, satirically critical magazines ever published. Its color was a flag, and its breed symbolized the snarling editorial policy of the weekly tabloid. Founded in 1896 in Munich, Germany, by a cadre of artists and writers that included Thomas Mann, Simplicissimus was fervently antibourgeois and unrepentantly Volkish (populist) in its rejection of materialism and modernization.

Simplicissimus, or der Simpl, as it was known, assailed German Kaiser Wilhelm II and his ministers, the Protestant clergy, military officers, government bureaucracy, urbanization, and industrialization while it lionized the peasant farmer and worker. The red bulldog symbolized the Volk, or common people, who were portrayed in the magazine’s cartoons and caricatures as feisty opponents to the ruling class, even if in reality this was an exaggerated view.

The authorities used stern measures to muzzle the dog, but despite frequent censorship and periodic arrests, this illustrated tabloid rarely missed an appearance. When it was finally confiscated by the police, the black, red, and white poster on which the bulldog stood poised reminded friend and foe alike that der Simpl would not be chained up for long. Rows of these posters—designed in 1897 by Thomas Theodore Heine (1867–1948), a cartoonist and co-editor of Simplicissimus—were hung for months at a time and were replenished regularly with fresh ones. Bans, on the other hand, lasted only a week or two and usually attracted more new readers than they discouraged.

The authorities used stern measures to muzzle the dog, but despite frequent censorship and periodic arrests, this illustrated tabloid rarely missed an appearance.

This was the power of Simplicissimus, the name borrowed from a fifteenth-century literary character, Simplicus Simplicissimus, who acted the fool around the aristocracy while tricking them into exposing their folly and corruption. This was Heine’s reason for designing a somewhat comic bulldog mascot instead of a more frightening graphic icon.

The red bulldog was just one weapon in der Simpl’s graphic arsenal. There were other mascots, though none as versatile. Whether it was the angry version from Heine’s poster or other, more comical iterations (including one of the bulldog urinating on the leg of an official), anyone looking for relief from Wilhelmian oppression could find an ally, at least once a week on paper, under the sign of the bulldog.

Der Simpl vehemently critiqued the status quo until the advent of World War I when it was conscripted as a tool of German propaganda. Even in its patriotic form it was biting, proving that humor could be effectively used for the wrong causes. After the war, during the 1920s and early 1930s, it resumed its critical stance attacking Italian fascism and the eme...