![]()

1

“If I Don’t Help Them, Who Will?”

The Working Life

At the age of fourteen, Joaquín identified an opportunity to earn extra money at his school to help his family. Joaquín’s mom was a sewing operator at a clothing factory in Pico Rivera and his father worked as a handyman. They provided for him and his two younger siblings, but as the oldest son, he wanted to help. Although he knew that school policy prohibited him from selling his wares at school, he did it anyway. With his extra backpack full of merchandise, Joaquín would spend recess with his customers, some of whom were also teachers. Joaquín remembered one day when a security guard at his school signaled for him to come over as he was dropping off books at his locker and picking up his “second” backpack. Joaquín’s friends looked at him with concern, but Joaquín walked over with confidence as he clutched his second backpack. At the end of the long hallway of metal lockers and blue-and-white checkered tile floor, the tall, muscular security guard waited for him with two dollars in hand. Joaquín took the money and, in exchange, gave him two small bags of chips and routinely asked whether he wanted Tapatio hot sauce.

Eighteen-year-old Joaquín laughed when he told me this suspenseful story in the living room of his house to explain his first experience vending food. His mother, Rosa, quietly shook her head and tried to control her laughter while she washed dishes in the kitchen. When Joaquín decided to sell chips, his parents were not street vendors, but one day he simply came up with the idea and told his mom, “Quisiera vender papas en la escuela” (I would like to sell chips at school)—and so he did. Joaquín opted to sell chips at school after seeing the demand for these types of snacks. He recalled, “A lot of people jumped the iron fence to go to the liquor stores” to buy chips because it was against school policy to sell chips and sodas inside the school premises. With enthusiasm Joaquín elaborated:

It got to the point where I had to take two backpacks full of chips because I was making money in high school. They already knew me. Every time I was at school, I was either doing my work or selling during my free time. They would come and they would ask me, “Do you have chips?” Teachers would ask me, too. The security guards used to buy my stuff. We had security in the halls to make sure we didn’t do graffiti. They would always see me with my bag and they would buy chips too.

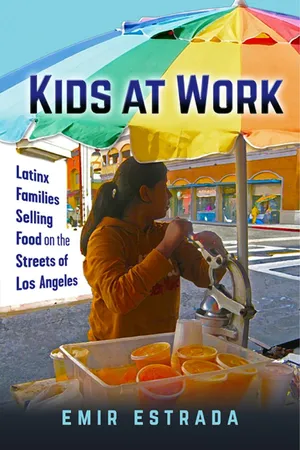

Figure 1.1. Boy making juice.

Little did Joaquín know that just one year later, circumstances would push him and his family to seek street vending as a financial alternative when his mother was fired from her job of fifteen years. Rosa had become ill over the years, and finally her employer decided to let her go, citing her undocumented status as a reason. She was fired with neither medical coverage nor severance pay. After Rosa lost her job, her husband became the only breadwinner. Again, Joaquín realized that his family was in need of help, and he chose to street vend with his uncles. Joaquín explained, “I went with my uncles one Saturday and I started vending. I helped them and noticed I made money. I said, I want to do this, and the first thing my uncle asked was if I was embarrassed.” Later, Rosa joined her son and together they sold fresh orange, carrot, and beet juice on Saturdays and Sundays at a busy business district in Los Angeles.

Joaquín continued going to high school while street vending and graduated on time. When I met him, he was a freshman at a state university in California, where he was double majoring in sociology and criminology. Sadly, Rosa did not see her son graduate from college. Two years after Rosa and her son started street vending, she was diagnosed with cancer and passed away while I was still conducting my study.

Figure 1.2. Girl making juice.

Joaquín’s story exemplifies the structural realities that motivate children to enact their agency in order to find economic solutions to help their parents. While it is well-documented why first-generation immigrants enter street vending, we know less about how and why children like Joaquín get involved in the family street vending business and what role they play in it.1

Street vending and family-pooled income strategies requiring that children work are common practices in countries like México.2 A good deal of research on child labor and street vending has been conducted in “developing countries” in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.3 However, these economic strategies are not uncommon in the United States.4 What explains this? Some commentators might assume that the children of immigrants engage in street vending in Los Angeles as a cultural holdover from México, their parents’ country. I argue that cultural explanations alone cannot explain why children and youth work as street vendors with their immigrant parents in East Los Angeles.

Structural Forces: “If I Don’t Help Them, Who Will?”

Joaquín’s story is also not unique among the children who shared their stories with me. All of the children in this study cited their parents’ lack of legal status and lack of access to formal sector work as the reason why they needed to help make ends meet. For example, Norma, who had just turned eighteen, and her younger brother Salvador, age twelve, faced an important decision to make when their father, Pedro, lost his job soon after they immigrated from México, where they had been living with their mother. Pedro left his wife and two children in México for ten years; in 2009 he used most of his savings to pay a smuggler to bring his family to Boyle Heights, California, where he used to share an apartment with other immigrants from his hometown.

Essentially, this family experienced profound ambivalence. On the one hand, they rejoiced at being together again after a long period of separation, and on the other hand, they faced the harsh economic reality of unemployment. Salvador was only two years old when his father immigrated to the United States; his father-son interactions mostly entailed weekly phone conversations and periodic gifts on his birthday. Norma has more vivid memories of her father before he left, but she too was having a difficult time adjusting to their new family arrangement in the United States.5 Before he brought his family to the United States, Pedro consistently sent remittances, and both Norma and her little brother Salvador focused entirely on their schoolwork.6 With his family now in Los Angeles, Norma’s father had to find a way to make money fast, but he was unable to find stable employment. When Norma’s father had the idea to sell tacos de barbacoa (goat meat), he first asked his children whether they would help. Norma explained,

My father asked us if we would agree to sell tacos de barbacoa on the street and he also asked if we could help him because they were not going to be able to do this on their own, and we said yes.

This is a typical conversation between parents and children when entering this occupation for the first time. This was unknown territory for all. Parents recognized that children’s help was important, and so was their opinion. After seeing the financial needs at home, moreover, the children made a conscientious and mature decision to help.

When I interviewed Norma and her family, they had been selling tacos de barbacoa in front of a junkyard for almost a year. The truck served as an improvised store tent, and a blue tarp stretched from the truck onto a hook Salvador helped screw on the wall. Salvador and his father were in charge of setting up their stand with two large folding tables, chairs for customers, and the skillet to heat up the meat and tortillas. Norma was almost always in charge of heating up the tortillas, while her mother and sometimes her father prepared the tacos and served a traditional birria broth in a separate cup (birria is a spicy stew made from goat meat). Salvador or one of the parents typically handled the cash transactions. During my time with this family, I saw Salvador inside the truck many times taking breaks and playing with his new portable video game, but after my interview with him, I discovered that he did most of his share of the work at home, the night before they street vend. Salvador told me that he is the one in charge of cooking the goat meat in the backyard of their house. When Salvador told me how he cooked the goat meat by himself, I could see a spark of pride, though he seldom looked up when he talked. At the young age of twelve, he had already become a master chef and was excellent at seasoning this traditional dish from their native town in Jalisco. Children like Salvador allowed me to see that there is more to street vending than the actual street work. Much of the work these kids do takes place off the streets because children are involved in many aspects of behind-the-scenes prep work. For example, while Salvador prepares and cooks the goat meat for several hours, Norma chops onions and cilantro inside their kitchen.

While children typically got involved in street vending work after their parents lost their jobs, soon they realized the importance of their work and family contribution. In many cases, refusing to help meant not being able to pay the rent, buy groceries, or even afford their own personal wants and desires such as toys, clothes, and technological gadgets.7 During my interview with fourteen-year-old Karen, she explained that she had convinced her mother to go back to street vending after she lost her iPod, a gadget that stored digital songs and pictures. In Karen’s case, there was no urgent need to street vend, but simply a desire to replace a very expensive toy that cost about $200. Her mother, Olga, recounted, “Entonces ella y yo volvimos a vender porque ella ahorita quiere un iPod” (So she and I started vending again because she now wants an iPod.) Karen understood that it is not just a matter of replacing an expensive gadget; rather, she must literally work to get a new one.8

Other children felt that they were the only help their parents had. Flor, who is getting ready to celebrate her quinceañera (fifteenth birthday), works with her mother on Saturdays. They sell cosmetics and snacks for pedestrians at a busy commercial area in Los Angeles. When I asked Flor why she helped her mother, she replied, “Si no les ayudo yo, quién?” (If I don’t help them, who will?) Children knew that street vending required extra help. Flor highlighted the importance of her work with a taken-for-granted example. She told me, “Sometimes I cover the stand while my mom goes to the bathroom.” This was important help, especially when vendors worked for long stretches at a time. As a researcher standing among street venders for hours at a time, even I was called on to help watch over a stand when someone had to run to the restroom at nearby restaurants.

Structural forces such as undocumented status and limited work for parents created opportunities for children to enter this occupation. However, children constantly highlighted their own agency in the process. Many rationalized their participation in street vending work with individual characteristics that, according to them, made them more apt for this type of work.

Which Children Choose to Street Vend in Los Angeles

Independent of structural forces, children in my study told me that their decision to street vend was their own. As a researcher, I was constantly aware of my position and wondered whether their responses were ex post facto rationalizations, and I remained unsure whether this was something they felt compelled to tell me. This is ultimately left for the reader to judge. The degree of their agency or free will was made more compelling when I learned that out of the thirty-eight children interviewed, twenty-four had siblings living at home who did not work with the family regularly or at all. Individual characteristics such as an outgoing personality or having people skills were often cited as good traits for street vendors. The children frequently defined themselves in opposition to their nonworking siblings who were too shy to do this type of work.

Fourteen-year-old Leticia, for example, had two brothers who stayed home while she worked with her mother. Leticia has a bubbly personality and seemed to be happy all the time. Her smile and laughter were very contagious. Their customers and I had a difficult time keeping a straight face when in the company of Leticia and her mom. While they constantly made fun of politicians, regular customers, and themselves, I had to be careful and stay on the periphery; otherwise I would also be fair game for teasing. According to Leticia, both of her brothers lacked her outgoing personality and were simply too shy. She was right. A few times, I saw her brothers quickly stop by their stand only to drop off merchandise for the business, such as tortillas, cheese, or vegetables. Other times, they simply stopped by to pick up food to eat. Leticia did not mind that her brothers did not work with them. Yet she justified her brothers’ lack of help:

The thing with my brothers is that they are very shy. They are not very social like me. I’m loud and talkative. They are calm and they say that I’m crazy. I guess I get it from my mom. She is always talking and always meets new people and I’m like that too. My brothers are shy. They don’t like to meet new people. I guess they are scared. When they come [to the street vending stand] they talk to people, but they just stand looking around like, “What do I do next?” and I’m just, like, “Well, come here, carry this and carry that.”

Similarly, Kenya said her older sister Erica simply lacked people skills to street vend. Unlike her, she did not have the personality needed to sell and handle rude customers. Kenya did clarify that Erica will help her mom as a last resort and only if no one else can help her:

Erica has gone [street vending] before, too. Whenever, like, I can’t go or my older sister couldn’t go. But she is like, “I just don’t like it. I can’t stand it there.” She is like, “I can’t sell like you guys do.” She doesn’t have people skills or anything. She is very nice, but she won’t go.

Sometimes children like Erica had siblings who were willing to work and thus shielded them from street vending responsibilities, but not from household work. While Erica could sometimes get away with not street vending, she often stayed home and helped with the household chores. There was certainly a gender dynamic at play, since girls who opted not to street vend—unlike boys—could not opt out of household work (see chapter 5). It is important to...