![]()

1

The ancient legacy

The unexamined life is not worth living.

Socrates

Due to their divergent philosophies, Plato and Aristotle launched opposing ways of thinking about the world that were at odds throughout the middle ages. Although some philosophers maintained that the ideas of the two great ancient philosophers could ultimately be harmonised, there was no widespread agreement about how this could be accomplished. The conflict between Plato and Aristotle actually proved to be very fruitful, however, because it pushed each side to make the best arguments possible.

Argumentation is the way philosophy progresses and logic is the backbone of argumentation. In order to understand what our medieval authors were trying to accomplish we will need to be able to dissect the structure of their reasoning. We therefore begin this chapter with a survey of the basic principles of logic that Plato, Aristotle, and their successors bequeathed to the middle ages.

The Socratic method

The word ‘logic’ comes from the Greek word ‘logos’ meaning reason. We use the same word at the end of our scientific disciplines, such as ‘biology’ and ‘psychology’ to mean ‘the systematic study of —.’ Logic is systematic study. It stipulates the rules of thought itself. Logic started in ancient Greece and became a sophisticated tool in the hands of medieval philosophers.

SOCRATES c. 470–399 BC

Socrates is known as the founder of Western philosophy.

Although Socrates was a sculptor by trade, he preferred to spend his time hanging around the public square in Athens and engaging passers-by in conversation. For example, Socrates might try to provoke a lawyer into a debate about the nature of justice. Because he was good at arguing and had a lot of interesting ideas, Socrates became known as a ‘philosopher’ from the Greek words for ‘love of wisdom.’ He attracted a following of fans.

Socrates also made a lot of enemies, however, by questioning authority and challenging the status quo. Eventually he was tried, convicted, and executed for impiety and corrupting the youth.

Socrates is the first on record to develop and employ a method of systematic study. It is called the ‘elenchus,’ meaning cross-examination. Although Socrates did not write any books, his student Plato wrote many books about him. Appropriately enough, the elenchus first appears in a work called The Apology, in which Plato describes a court trial at which Socrates had to defend his own reputation.

During the trial, Socrates announces that God revealed to him that he is the wisest among men. Admitting that he himself did not at first believe the revelation, he proceeds to show how, and in what sense, he learned it to be true.

MY DEFENCE

After long consideration, I finally thought of a method of testing the question. I reflected that if I could find someone wiser than myself, then I might go to God with a refutation in my hand. I would say to God: ‘You said that I was the wisest, but here is someone who is wiser than I am!’

Accordingly, I went to a man who had a reputation for wisdom and the result was as follows: When I began to talk with him, it became evident that his supposed ‘wisdom’ consisted in the fact that he thought himself to be wise. When I tried to explain that thinking you are wise is not the same as being wise he grew to hate me. So I left him, saying to myself as I went away: ‘Well, even though neither of us is wise, I’m better off than he is. For he claims to know things that he doesn’t really know; whereas I neither know nor think that I know. In this way, I seem to have a slight advantage over him.’

Then I went to another man who had even higher philosophical pretensions and my conclusion was exactly the same. I made another enemy of him, and of many others besides him, as I went from one to another searching for a wise man.

The truth I learned, O people of Athens, is this: only God is wise. God’s revelation to me was meant to be humbling. He was using me as an illustration, as if to say: ‘the wisest person is the one who, like Socrates, knows that his “wisdom” is in truth worth nothing.’

As demonstrated in this passage, the elenchus is a powerful way to refute your opponent. It is therefore useful, not just in court, but in any philosophical debate.

We can appreciate the structure of the argument more clearly if we rewrite it in schematic form as follows:

To Prove: Socrates is the wisest person.

1. Suppose Socrates is not the wisest person.

2. If Socrates is not the wisest person, then other people must be wiser.

3. All the other people claim to know things they don’t really know.

4. It would be absurd for a wise person to claim to know things he or she doesn’t really know.

5. Therefore, Socrates is the wisest person.

Notice that if you accept steps (1) through (4), then you can’t deny step (5). In the middle ages, this method of argumentation came to be called ‘reductio ad absurdum,’ which is Latin for ‘reduction to an absurdity.’ It is still widely used today. The goal is not to show that your opponent is silly or laughable, but rather to show that his view implies something that cannot possibly be true. In philosophy, the word ‘absurdity’ refers to an impossibility or contradiction.

Validity

Although Socrates typically preferred to use the elenchus method in his arguments, Plato’s student Aristotle realized that there are a number of other equally compelling ways to make one’s case. In the following passage from a work called Prior Analytics, Aristotle develops a general criterion for classifying and evaluating different kinds of arguments.

LOGIC BASICS

A ‘premise’ is a statement affirming or denying one thing with respect to another. It must be universal, particular, or indefinite. By ‘universal’ I mean the statement that something belongs to all or none of something else; by ‘particular’ I mean the statement that something belongs to some, or not to some, or not to all of something else.

A ‘syllogism’ is an argument in which, certain things being stated (the premises), something other than what is stated (the conclusion) follows of necessity from their being so. That is, the premises produce the conclusion: no further term is required from without in order to make the conclusion necessary.

First, take a ‘universal negative’ premise using the terms A and B. If no B is A, neither can any A be B. For if some A (say C) were B, it would not be true that no B is A; for C is a B.

Next, consider a “universal positive.” If every B is A, then some A is B. If no A were B, then no B could be A. But we assumed that every B is A.

Now take a ‘particular positive’ syllogism with the terms A and B. If some B is A, then some of the As must be B. If none were, then no B would be A.

Finally, if some B is not A, then there is no necessity that some of the As should not be B; e.g. let B stand for animal and A for human being. Not every animal is a human being; but every human being is an animal. This is a ‘particular negative’ syllogism.

In this groundbreaking exposition Aristotle defines the crucial concept of ‘syllogism,’ which medieval philosophers later called ‘deductive validity,’ from the Latin verbs deducere, meaning ‘to lead down,’ and valere, meaning ‘to be strong or successful.’ The conclusion of a deductively valid argument follows from its premises with necessity.

The necessity of a deductively valid inference is evident in the four types of arguments Aristotle discusses. We should examine them in closer detail.

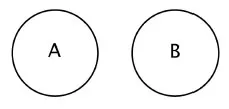

1. Universal Negative

No apple (A) is a banana (B).

This sentence says that the set of apples does not intersect with the set of bananas.

As the diagram shows, the sentence clearly supports the further inference Aristotle draws, that if no A is B, then no B is A.

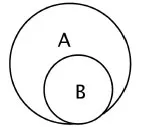

2. Universal Positive

Every bug (B) is an annoyance (A).

This sentence says that the set of bugs is a subset of the set of annoyances.

As the diagram shows, the sentence clearly supports the further inference Aristotle draws, that if every B is an A, then some A is a B.

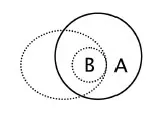

3. Particular Positive

Some boy (B) is an African (A).

This sentence says that at least one boy is a member of the set of Africans.

We don’t know from the sentence whether B intersects with A or is a subset of A. These two possibilities are represented with dotted circles on the diagram. All we know for sure, as Aristotle infers, is that if some B is A, then some A must be B.

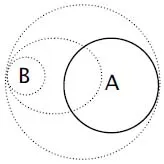

4. Particular Negative

Some animal (B) is not a human being (A).

This sentence says that the set of animals is not a subset of the set of human beings.

As Aristotle notes, the sentence does not support the inference that some of the As are not Bs. As the dotted circles on the diagram show, we can’t tell from the sentence whether A is a subset of B, or whether it intersects, or whether it does not intersect at all.

This failure of inference makes a crucial point. When Aristotle defines ‘syllogism’ in the above passage he says that the premises must produce the conclusion in such a way that ‘no further term is required from without in order to make the conclusion necessary.’ Obviously, we all know that the set of human beings is a subset of the set of animals. But logic does not allow us to import information from the outside to arrive at a conclusion. This would be like saying 2 + 2 = 5 because we can always add a 1 from somewhere ...