A Eye Shape, Stereopsis, and Acuity

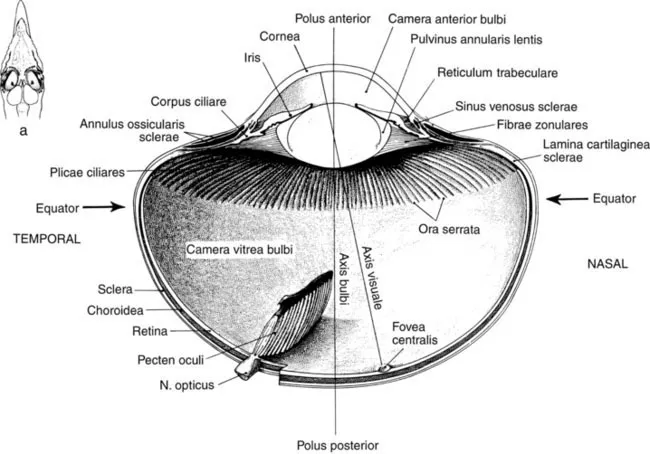

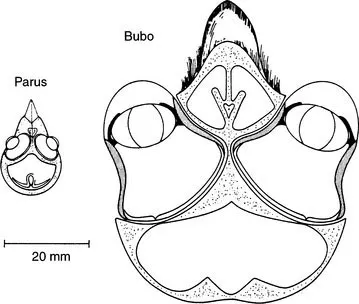

The eyeshapes of birds are a result of ecological requirements (Figure 2). Generally, acuity can be maximized by increasing the anterior focal length of an eye; the optic image is then spread over a larger retinal surface and thus over a larger number of photoreceptors (Martin, 1993). Increasing the number of photoreceptors also makes it possible to connect several receptors to single bipolar cells and thus to maximize visual detection even under low light conditions. Since an increase in eye size is advantageous, birds, which rely heavily on vision, generally have the largest absolute and relative eyes within the animal kingdom. The eye of the ostrich, for example, has an axial length of 50 mm, the largest of any land vertebrate and twice that of the human eye (Walls, 1942). The tube-shaped eyecups of birds of prey, which create an extremely large image on the retina, represent another extreme version of biological optimization to achieve high acuity. These eyes generally also have a low retinal convergence ratio (receptors per ganglion cell) so that the receptor inputs are not pooled to increase visual resolution (Snyder et al., 1977). However, these optimizations are limited by trade-offs for brightness sensitivity. Retinae in which receptors are not pooled function only optimally at high light intensities and, indeed, resolution of birds of prey deteriorates at dusk (Reymond, 1985).

Visual acuity measurements in pigeons (Columba livia) have shown that the acuity in the frontal field depends on stimulus time (Bloch and Martinoya, 1982), wavelength of light (Hodos and Leibowitz, 1977), luminance (Hodos et al., 1976; Hodos and Leibowitz, 1977), and age of the pigeon (Hodos et al., 1991a). Under favorable conditions 1-year-old pigeons reach a frontal acuity of 12.7 c/deg, increase this value to 16–18 c/deg at 2 years, and decline to 3 c/deg at 17 years (Hodos et al., 1985, 1991b). The frontal binocular visual field of pigeons is represented in the superiotemporal area dorsalis, while the lateral monocular visual field is observed via the area centralis (both lack a true foveal depression). These two retinal regions seem to subserve different visual functions with differing capacities for optic resolutions. Behavioral studies show that many avian species, including pigeons, fixate distant objects preferentially with their lateral and monocular field (pigeon: Blough, 1971; dove: Friedman, 1975; kestrel: Fox et al., 1976; eagle: Reymond, 1985; passerine birds: Bischof, 1988; Kirmse, 1990). This behavior is often pronounced; birds orient themselves sideways in order to achieve a lateral orientation to the inspected object. This behavior, together with the fact that retinal ganglion cell densities reach peak values in the central fovea, suggest that resolution is maximal in the lateral visual field. However, the acuity of young pigeons is 12.6 c/deg in their lateral visual field and thus identical with the values obtained for frontal vision in same aged subjects (Hahmann and Güntürkü...