eBook - ePub

Complete Guide to Making Wooden Clocks, 3rd Edition

37 Woodworking Projects for Traditional, Shaker & Contemporary Designs

John A. Nelson

This is a test

Partager le livre

- 250 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Complete Guide to Making Wooden Clocks, 3rd Edition

37 Woodworking Projects for Traditional, Shaker & Contemporary Designs

John A. Nelson

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

Learn how to construct a variety of traditional, Shaker, and contemporary clocks, with plans, parts lists, and instructions for 37 timepieces, including grandfather clocks, mantel clocks, and desk clocks.Complete Guide to Making Wooden Clocks, 3rd Editionalso includes a bonus pattern pack with scroll saw project templates.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Complete Guide to Making Wooden Clocks, 3rd Edition est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Complete Guide to Making Wooden Clocks, 3rd Edition par John A. Nelson en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Tecnología e ingeniería et Oficios técnicos y manufactureros. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

CHAPTER 1

A Brief History of Clocks

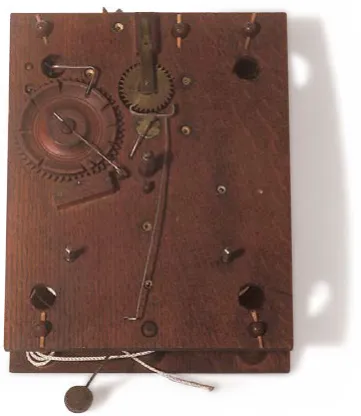

The theory behind time-keeping can be traced back to the astronomer Galileo. In 1580, Galileo, who is well-known for his theories on the universe, observed a swinging lamp suspended from a cathedral ceiling by a long chain. As he studied the swinging lamp, he discovered that each swing was equal and had a natural rate of motion. Later he found this rate of motion depended upon the length of the chain. For years he thought of this, and in 1640, he designed a clock mechanism incorporating the swing of a pendulum. Unfortunately, he died before actually building his new clock design.

In 1656, Christiaan Huygens incorporated a pendulum into a clock mechanism. He found that the new clock kept excellent time. He regulated the speed of the movement, as it is done today, by moving the pendulum bob up or down: up to “speed-up” the clock and down to “slow-down" the clock.

Christiaan’s invention was the boon that set man on his quest to track time with mechanical instruments.

EARLY MECHANICAL CLOCKS

Early mechanical clocks, probably developed by monks from central Europe in the last half of the thirteen century, did not have pendulums. Neither did they have dials or hands. They told time only by striking a bell on the hour. These early clocks were very large and were made of heavy iron frames and gears forged by local blacksmiths. Most were placed in church belfries to make use of existing church bells.

Small domestic clocks with faces and dials started to appear by the first half of the fifteenth century. By 1630, a weight-driven lantern clock became popular in the homes of the very wealthy. These early clocks were made by local gunsmiths or locksmiths. Clocks became more accurate when the pendulum was added in 1656.

Early clock movements were mounted high above the floor on shelves because they required long pendulums and large cast-iron descending weights. These clocks were nothing more than simple mechanical works with a face and hands and were called “wags-on-the-wall.” Long-case clocks, or tall-case clocks, actually evolved from the early wags-on-the-wall clocks. They were nothing more than wooden cases added to hide the unsightly weights and cast-iron pendulums.

JOHN HARRISON (1693–1776)

Little is known about this man, the one person who, I think, did the most for clock-making. John was an English clockmaker, a mechanical genius, who devoted his life to clock-making. He accomplished what Isaac Newton, known for his theories on gravity, said was impossible.

John Harrison was born March 24, 1693, in the English county of Yorkshire. John learned woodworking from his father, but taught himself how to build a clock. He made his first clock in 1713 at the age of 19. It was made almost entirely of wood with oak wheels (gears). In 1722 he constructed a tower clock for Brocklesby Park. That clock has been running continuously for over 270 years.

One year later, on July 8, 1714, England offered £20,000 (approximately 12 million dollars) to anyone whose method proved successful in measuring longitude. Such a device was desperately needed by navigators of sailing vessels. Sailors during this time were literally lost at sea as soon as they lost sight of land. One man, John Harrison, felt longitude could be measured with a clock.

John Harrison

During the summer of 1730, John started work on a clock that would keep precise time at sea—something no one had yet been able to do with a clock. In five years he had his first model, H-1. It weighted 75 pounds and was four feet tall, four feet wide and four feet long. To prove his theory, John built H-2, H-3 and H-4.

His method of locating longitude by time was finally accepted and he won the prize. It took him over 40 years. Today, his perfect timekeeper is known as a chronometer.

CLOCKS IN THE COLONIES

In the early 1600s, clocks were brought to the colonies by wealthy colonists. Clocks were found only in the finest of homes. Most people of that time had to rely on the church clock on the town common for the time of day.

Most early clockmakers were not skilled in woodworking, so they turned to woodworkers to make the cases for them. These early woodworkers employed the same techniques used on furniture of the day. In 1683, immigrant William Davis claimed to be a “complete” clockmaker. He is considered to be the first clockmaker in the new colony.

Great horological artisans immigrated to the New World by 1799. Most of these early artisans settled in populous centers such as Boston, Philadelphia, New York, Charleston, Baltimore and New Haven.

Clock-making grew in all areas of the eastern part of the colonies. The earliest and most famous clockmakers from Philadelphia were Samuel Bispam, Abel Cottey and Peter Stretch. The most famous clockmaker was Philadelphia’s David Rittenhouse. David succeeded Benjamin Franklin as president of the American Philosophical Society and later became Director of the United States Mint.

Most Early American clocks had wooden gears, as brass was very expensive and hard to obtain.

NINETEENTH CENTURY GRANDFATHER CLOCKS

Inexpensive tall-case clocks were made in quantity and became more affordable after 1800. The clock-making industry spread to the northeastern states. In Massachusetts, Benjamin and Ephram Willard became famous for their exceptionally beautiful long-case clocks. In Connecticut, mass-produced long-case clocks were developed by Eli Terry.

In early days, almost all clock cases were made by local cabinetmakers. A firm that specialized in clock works fashioned the wood or bronze works. Cabinetmakers engraved or painted their names on the dial faces, thereby taking claim for the completed clocks.

With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, regular factory working hours and the introduction of train schedules, standardized timekeeping became a necessity. Clock-making moved to the forefront.

Wooden movements were abandoned in 1840 and 30-hour brass movements became popular. They were easy to make and inexpensive. Spring-powered movements were developed soon after. A variety of totally new and smaller clock cases appeared on the market.

NINETEENTH-CENTURY MANUFACTURERS

Clock manufacturers were mostly individual clockmakers of family-owned companies. After 1840 however, Chauncy Jerome built the largest clock factory in the United States. He started shipping clocks all over the world. The Jerome Clock Company motivated the organization of the Ansonia Clock Company and the Waterbury Clock Company. These three companies, along with Seth Thomas Company, the E. N. Welch Company, the Ingraham Clock Company, and the Gilbert Clock Company, became the major producers of clocks in the nineteenth century. There were over 30 clock factories in this country by 1851. From 1840 up to 1890, millions of clocks were produced in this country, but unfortunately, very few still exist intact today.

Elias Ingraham

Elias was born in 1805 in Marlborough, Connecticut. He served a 5-year apprenticeship in cabinetmaking in the early 1820s. By 1828, at the age of 23, Elias was designing and building clock cases for George Mitchell. When he was 25 years old, he worked for the Chauncey and Lawson Ives Clock Company, which was still designing and building clock cases.

Elias formed a new company with his brother Andrew in 1852 called the E. and A. Ingraham and Company, but 4 years later, it went bankrupt. A year later he formed his own company with his son, Edward. Changing the name to E. Ingraham and Company, the business began ...